My previous post told the story of the development of the London suburb of Kensal Town. It is an area rich in history and one of its places of history was the Cobden Working Men's Club on Kensal Road.

One for his nob

I was all for not grandstanding my own story in the previous post on here but this is a new week and a different article. The Cobden Club was the location of a children's party where I won my first camera in a raffle around 1970 and thus I feel the need to delve into this place a bit. Why was it there? Who or what was Cobden?

My maternal grandfather was a member of the Cobden Club and disappeared into its bowels quite regularly. Given his other life choices (outside being a wonderful granddad) I assume that he went there for cheaper beer and games of cribbage.

Perhaps he was there to continue Fabian initiatives to educate the working classes but he would use the word ‘Muggins’ too much for this to be the case.

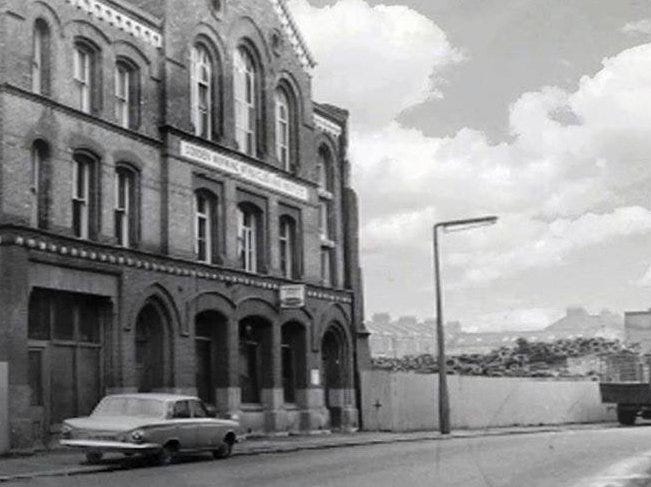

This is what the ‘Cobden’ looked like around the time I won that camera. The area was yet to be the sort of place that supermodels wanted to move into. There’s a wonderfully grimy Ford Cortina Mk 1 parked halfway up the pavement. Next door is a dump for old tyres. And there is one of those distinctive 1960s lampposts which were put up all over the Borough of Kensington from here in working-class Kensal Town up to the very poshest Notting Hill houses at the Holland Park end of Ladbroke Grove.

Let's find out about the Cobden behind the Cobden Club.

He wasn't a 'what' but a 'who'. Richard Cobden - the son of an impoverished farmer - became extremely well-known and fêted during and immediately after his lifetime. So much so that there is a statue of him, partially funded by public subscription on the square in front of Mornington Crescent tube station. (The Cobden pub on Camden High Street is in turn named after the nearby statue). Few people remember him now.

And when I write “partially funded by public subscription“, I need to point out that the majority of the funding for the statue came from French emperor, Napoléon III.

That requires some explanation. Farmer’s son? French emperor?

Richard Cobden was born on 3 June 1804 in Heyshott, Sussex, the fourth of 11 children. His family faced financial difficulties when his father William's farming ventures failed, forcing multiple moves before settling as tenant farmers in West Meon, Hampshire by 1814.

The young Richard had an uncle - Richard Ware Cole. One of Richard Cobden’s older brothers would be the eventual heir to the farm and so at age 15, Richard went to London to work in his uncle's warehouse business as a commercial traveller in muslin and calico.

He turned out to be remarkably skilled in the world of muslin and calico and in 1828, Cobden set up his own business with partners. In 1831 they leased a calico printing factory at Sabden, near Clitheroe, Lancashire. He settled in Manchester in 1832, where the business prospered and ‘Cobden prints’ became known for their quality.

Richard Cobden became exceeding wealthy. In order to further expand the business, he began to travel the world and began to see how other countries organised their societies.

He became convinced about how working-class living conditions within Manchester were being stymied by the doctrine of protectionism then prevalent in Britain.

After visiting the United States, then based very much on a laissez-faire system, he published his first pamphlet, entitled ‘England, Ireland and America’ in 1835.

He travelled to Russia, Spain, Turkey and Egypt during 1836-1837, developing his ideas about international relations and free trade. Upon returning to Britain in 1837, he became active in Manchester's political and intellectual life.

In 1838, Cobden and John Bright founded the Anti-Corn Law League, aimed at abolishing the unpopular Corn Laws.

Cobden at this time married Catherine Anne Williams, a Welsh woman, and they had five surviving daughters. Their only son died at age 15 from scarlet fever.

Continuing to publish his views, Richard Cobden began public speaking, cementing his popularity. In 1841, he was elected as Member of Parliament for Stockport. For seven years, he served as the League's chief spokesman, campaigning tirelessly against the protectionist laws. The campaign succeeded in 1846 when Sir Robert Peel called for repeal of the Corn Laws.

After the Corn Laws victory, Cobden embarked on a mission across Europe, visiting France, Spain, Italy, Germany and Russia to promote free trade principles. He was honoured everywhere he went and had audiences with leading statesmen.

After opposing British actions in China regarding the ‘Arrow Incident’, Cobden lost his parliamentary seat in 1857 following Palmerston's defeat. He spent time at his country house at Dunford before visiting the United States again. In the 1859 general election, he was returned unopposed for Rochdale.

Towards the close of 1859, Cobden initiated negotiations with Napoleon III and French ministers to promote freer commercial relations between Britain and France.

Cobden’s health deteriorated with bronchial problems, forcing him to spend winters in warmer climates like Algeria. On 2 April 1865, he died peacefully at his apartments in London and was buried at West Lavington church in West Sussex on 7 April.

The year after his death, the official Cobden Club was founded in 1866 by Thomas Bayley Potter, Cobden's successor at his Rochdale parliamentary seat, to promote Peace, Free Trade and Goodwill Among Nations.

The Cobden Club was run along the lines of a gentlemen's club of the Victorian era, but without permanent club premises of its own. It was not even a "club" in a proper sense - it had no facilities or regular meetings, save for an annual dinner, but was more akin to a society with membership open to the public.

Unusually for contemporary clubs, it had a publishing arm. The publishing arm was instrumental in publishing Cobden's collected speeches in 1870, under the co-editorship of John Bright. The club energetically diffused free trade literature.

The Club attracted notable members both in Britain and internationally. Early US Cobden Club members included Boston abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, Boston economist Edward Atkinson, as well as various members of the Adams family - no, not that one.

With the fading of Free Trade as a popular cause, the club fell into decline in the 20th century. It closed at the end of the 1970s.

That was the story of the real Cobden Club but not my Cobden Club.

A capricious turn to this story

The Cobden Working Men's Club was founded in Kensal Town, completely separate from the elite Cobden Club. Seemingly there was some sort of tussle about the name with the official organisation but the London W10 version seems to have held out. Brand names were less protected in the Victorian period.

The club was built as part of a Fabian initiative to educate the working classes and is the earliest known surviving purpose-built working men's club in London.

The building was designed by architects Nathan Glossop Pennington and Thomas Edward Bridgen in 1880.

A commemorative mallet was presented at the opening of the Cobden Working Men's Club. The inscription on this artefact reads:

Presented to N.G. Pennington, Esq by the members of the Cobden Working Mens Club, Nov. 6th 1880.Pennington and Bridgen designed most of their other buildings in Manchester - a nice connection with Richard Cobden.

An architectural search on Google gleans the facts that the building was ‘constructed of grey brick with red brick dressings and ground floor, on Portland stone plinth. Three storeys high, with staircase set either side of bars on two lower floors, with double-height theatre above extending into projecting gable’.

Never mind that, the building had many original features, including an upper floor ‘song room’, where at one time future US President Bill Clinton played his saxophone as a student.

In an area full of pubs - was this the best-served area of any in London? - the Cobden competed with lower prices and many features more akin to a music hall. Apparently it boasted more than three pianos.

It remained a social centre for the neighbourhood for more than 100 years. It still had as many as 400 members in 1983.

Times they are a-changing

"I've spent my whole life in taxis going to Soho. There's a crying need for a club in Notting Hill" said Ivo Hesmondhalgh, director of the revamped Cobden Club in 1996. Mr Hesmondhalgh was using local estate agents’ then-recent redefinition of the term ‘Notting Hill’ to include areas nowhere near the eponymous hill.

The society set up for earnest political discourse and further education had gone suddenly bankrupt and the building became a watering hole for the chattering classes.

According to a contemporary article in The Independent, the 'working men' would be allowed to stay on the ground floor for a peppercorn rent (a bottle of whisky per annum) while the new club's members - the likes of Will Self and Amanda de Cadenet - could sip their designer beers upstairs.

There were to be separate entrances. Words fail me here but luckily that travesty in turn closed down in 2010.

The building was then bought to be her home by ‘supermodel’ Caprice (Bourret) but it retains its Grade II listed status as an important example of Victorian working men's club architecture.

They’re coming to take me away

Now where were we with that statue?

Napoléon III contributed to funding the Cobden statue beside Mornington Crescent station as a gesture of diplomatic gratitude for Richard Cobden's crucial role in negotiating the Cobden-Chevalier Treaty of 1860. Cobden had a long audience with Napoléon in 1859, urging arguments in favour of removing obstacles between the two countries and succeeding in making a considerable impression on his mind in favour of free trade.

The 1860 treaty was enormously beneficial to both nations, particularly France. It ended tariffs on main trade items—wine, brandy and silk goods from France, and coal, iron and industrial goods from Britain, causing the value of British exports to France to more than double in the 1860s while French wine imports to Britain also doubled. The Repeal of the Corn Laws had opened the British market to French grain, and Napoléon wanted to honour the main politician behind free trade.

When Cobden died in 1865, the French foreign minister called his death "a cause of mourning for France and humanity," describing him as "an international man" who represented "cosmopolitan principles before which national frontiers and rivalries disappear".

My grandad meanwhile honoured Richard Cobden in his own way - becoming excellent in the counting of cards totalling 15.

Thank you, Scott. You have gift for bringing the obscure and unusual to light - this was another intriguing post.

That old photo of the club next to a tyre dump is incredible - The area was even less "Notting Hill" back then! I love the solidity and grand proportions of the building - it reminds me of the Peabody estates that were built at around the same time, with a similar sense of ambition.