Stradling Harrow Road from the eastern side of the junction with Ladbroke Grove was one of London’s political curiosities - ‘Chelsea Detached’.

This was a portion of land belonging to the parish of Chelsea but located miles away from the King’s Road. Until 1900, the parish of Chelsea included this detached portion of about 120 acres which lay beyond the northern end of Kensington and even into Willesden. This arrangement possibly originated from a single Anglo-Saxon landholding unit being split up.

While it may seen an innocuous anomaly - swept away when sensible people took over - it had a great effect on how this part of London was developed.

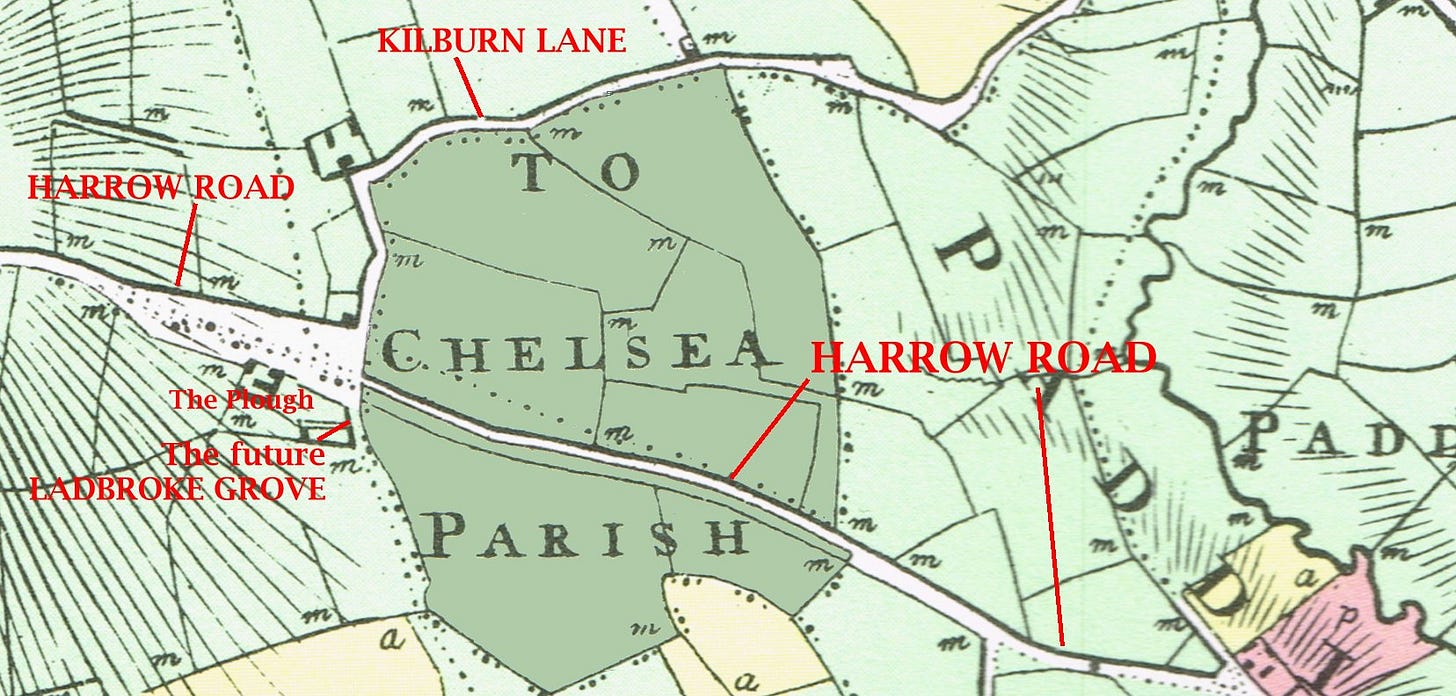

Above is an extract from the Milne landuse map dating from 1800 to try to get some bearings. The ‘avocado green’ area is Chelsea Detached and I’ve tried to add some clarification with all my red annotations. We have Harrow Road running west-south east. At the Plough is the current Harrow Road/Kilburn Lane/top of Ladbroke Grove junction. St John’s Church is also at the modern junction.

At the time of this map, Chelsea Detached was mostly enclosed meadows, troubling nobody with their weird administration having been assigned to St Luke’s church, a long way away. All the fields were pasture, except for a wooded enclosure beside Kilburn Lane almost opposite Kilburn Wood. The few farm buildings that existed were all on the Willesden side of the lane.

But things were to change.

The Grand Junction Canal was cut just south of Harrow Road in 1801, leaving about a third of Chelsea Detached to the south of it.

Being itself cut off from the rest of Chelsea Detached, this area became known as Chelsea-in-the-Wilderness. Some navvies who had cut the canal, settled south of it - these first informal dwellers may have been joined by Romany settlers too. Around 1835, the development of the area became a bit more organised and the appellation Kensal Town was applied. Many of these shanty towns of London for itinerant workers building the canals and then the railways received the suffix ‘Town’. Agar Town was another one in Camden. Tomlins Town in Paddington was one of the first - long buried under the Marylebone Road. Perhaps Canning Town and Cubitt Town were also in that tradition as philanthropist industrialists started building dwellings.

The Kensal part of the name came from the hamlet of Kensal Green to the west of Kilburn Lane. A lane led up from the south which was called Portobello Lane and this passed over a new bridge spanning the canal. The new town was served from 1843 by St John's church, on the other side of the bridge and which even in 1865 stood with only two nearby houses and a National school.

The Great Western Railway, skirting the south of the exclave opened in 1838. This caused huge isolation - the new residents were hemmed in by a canal to the north and the railway to the south. It was an increasingly very poor area and pig keeping was a major focus at the beginning.

Over time, the naming conventions evolved. Kensal Town eventually became the formal designation for the entire Chelsea Detached exclave, while Kensal New Town continued to refer specifically to the development south of the canal.

Within Kensal New Town, five roads were laid out in the early 1840s. Four had utterly unimaginative names: West Row, Middle Row, East Row and South Row. The fifth was the main road through the area and named Albert Road after the new Prince Consort.

A pub was established at the junction of this new main road with another new road stretching back into Kensington Parish called Britannia Road. This pub was called the Albert for a while and then the Britannia.

Both road names mentioned soon fell out of use. Albert Road became Kensal Road and Britannia Road was renamed Golborne Road. The pub which lasted into modern times bore the names in turn of both old road names.

The newly constructed Kensal New Town quickly became home to a substantial Irish immigrant community. This demographic influence remains visible today in the significant number of Catholic churches in the surrounding area. The area also featured a huge number of pubs which have all disappeared since the 1960s.

The Western Gas Works were built at the top of what became Ladbroke Grove, providing new employment opportunities for the men of the area. The women of the area turned largely to laundry work. Laundries along Kensal Road were still a feature well into the twenty first century

Apart from the bridge near St John’s church, another way out to Harrow Road and to the rest of London was by using a ferry which cost users a halfpenny. This was in time replaced by steps on the site of the ferry. Thankfully the steps were now free to use but became known as the Ha’penny Steps.

But enough of social history and back to my real love - maps.

Above is an extract of the rather beautifully-engraved late 1860s Ordnance Survey map and we’re about to take a close look at some quite interesting quirks.

We see the St Luke Chelsea parish name at the top of the extract. This is written over the fields which would later became the Queen’s Park Estate. To the right of the letter A is a dotted boundary line running north-south at this point. Along the dotted line are various BS abbreviations, marking the boundary stones of Chelsea. A slight kink but the dotted line crosses Harrow Road and then the canal and comes to a ‘T junction’ where Chelsea, Kensington (to the south) and Paddington (to the east) parishes all meet.

The dotted line continues westwards in a satisfying curve - over the railway and back again. It turns northwards to meet Harrow Road at the (sadly gone now) Plough inn.

It is notable that the entire Kensal New Town development was laid out strictly within the confines of Chelsea Detached. Roads, houses and gardens stopped dead at the boundary. They went no further outside their parish for the following fifty years after being laid out. There’s a tiny enclave of Chelsea south of the railway which wasn’t build upon, as all access roads would need to be built in Kensington and that wasn’t (yet) going to happen.

Ladbroke Grove was not a name. This road was built in stages from Holland Park Avenue and straight as a die. Whether by accident (or design decades earlier), this completely straight route reached the bridge beside the gas works without any deviation during the 1860s. It took over the route of what had been Portobello Lane. South of the GWR, Ladbroke Grove and Portobello Lane diverged and the lane was renamed Portobello Road.

Speaking of Portobello, Portobello Bridge crosses the railway on the line of soon-to-come Golborne Road.

In the 1870s, the first section of the Queen’s Park Estate was built north of Harrow Road, at first exactly confined within St Luke’s Chelsea.

It was built from 1874 by the Artisans, Labourers & General Dwellings Company. The architecture of that estate of some 2000 small houses is distinctively Gothic-revival, with polychrome brickwork, pinnacles and turrets along the bigger roads. There were no pubs as the working classes here were to be ‘improved’. There was though a library on Harrow Road for cultural needs, bypassed by drinkers heading for the myriad hostelries of Kensal New Town over the Ha’penny Steps.

Road naming in Queen’s Park was as surreal as Kensal New Town. Each new road was either numbered or took consecutive letters of the alphabet. In Kensal Town they had been named after compass points.

The Queen’s Park Estate retains First Avenue, Second Avenue etc up to Sixth Avenue, and originally had streets simply called A-P. These street names were deemed too boring by somebody and were made into full words: Alperton Street, Barfett Street, Caird Street, Droop Street, Embrook Street, Farrant Street, Galton Street, Huxley Street, Ilbert Street, Kilravock Street, Lothrop Street, Marne Street, Nutbourne Street, Oliphant Street, Peach Street.

On the above 1890s map of the area north of Harrow Road we can see the dotted line of the Chelsea parish boundary running north to south. The Queen’s Park Estate avenues and A-P streets were built west of the border and the roads to the east of the line only built later.

One field was left after all the 1870s building and then Mozart Street and Lancefield Street built on the field, bucking the naming convention. But the field boundary can still be seen in the changes of housing layouts. A football team which was formed by St Jude’s Church (north on the map) moved around a lot and settled in London W12 as Queen’s Park Rangers - named for the estate.

Continuing this extract south, we can again see the parish boundary very clearly. The ‘Row’ streets to the west; newer roads to the east. Property boundaries still follow the border. Stockton Mews is strictly built outside the confines of Chelsea in a boundary kink. At the Bosworth Road/Appleford Road/South Row junction - on the south side - the parish boundary stone BS is still visible in the pavement in 2025.

Building pressure during the 1880s caused the development of Bosworth Road, Adair Road and the others on the Kensington side of the border. A similar story happened on the Queen’s Park Estate.

In 1900, despite strong local resistance, the Kensal Town exclave was separated from Chelsea and split amongst adjacent areas. The southern portion below the canal united with Kensington's ancient parish to establish the new Metropolitan Borough of Kensington. The northern section above the canal combined with Paddington's ancient parish to create the new Metropolitan Borough of Paddington.

The region continued as part of Chelsea's parliamentary constituency (which shared exact boundaries with Chelsea's former parish) until 1915. When the local MP for Chelsea, Emslie Horniman, presented an acre of ground between East Row and Bosworth Road to the London County Council in 1911 for recreational purposes, he noted that there was then "no place within a mile or more where children could play, except in the streets, nor anywhere for the mothers and old people to rest". The park was later expanded and is now known as Emslie Horniman Pleasance and it is now a gathering point for the Notting Hill Carnival.

NOTES

For no real reason, South Row was renamed Southern Row. To enable Ladbroke Grove to cross two bridges (railway and canal) it had to be built on an embankment above the ground level of Southern Row. This is why steps are needed to get from Kensal Town up to Ladbroke Grove here. These steps appear in all sort of films and photographs needing to depict a grimy vision of London - much featured on LP album artwork.

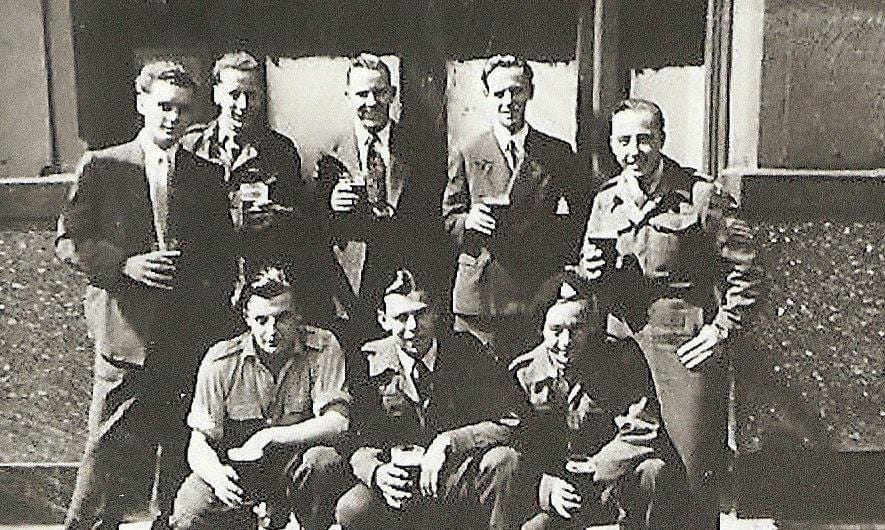

I decided not to go into my own personal history of Kensal Town as I’d fill up reams of material. Both sides of my family lived there, my parents met there and got married there. I lived in East Row for the first six months of my life - our house was demolished to make way for an extension to the Emslie Horniman Pleasance. But here’s my Dad and his chums outside the Plough on Harrow Road.

Really enjoyed reading about the history of Kensal Town, an area which I recently explored.

It’s striking how the land use in that part of town is so dictated by the positioning of the canal, railway line and the Westway.

One thing that caught my eye was the Cobden Working Men’s Club, a throwback to a different era.

Interesting to hear about your personal connection with the area.

Such an interesting post. Mentioning the mythical Ha'penny Steps which were out of my territory...