The Old Kent Road is famous as the cheapest property on the London Monopoly board. A little later we’re going to take a ‘butchers’ at the road in question but first it’s time for a little back story.

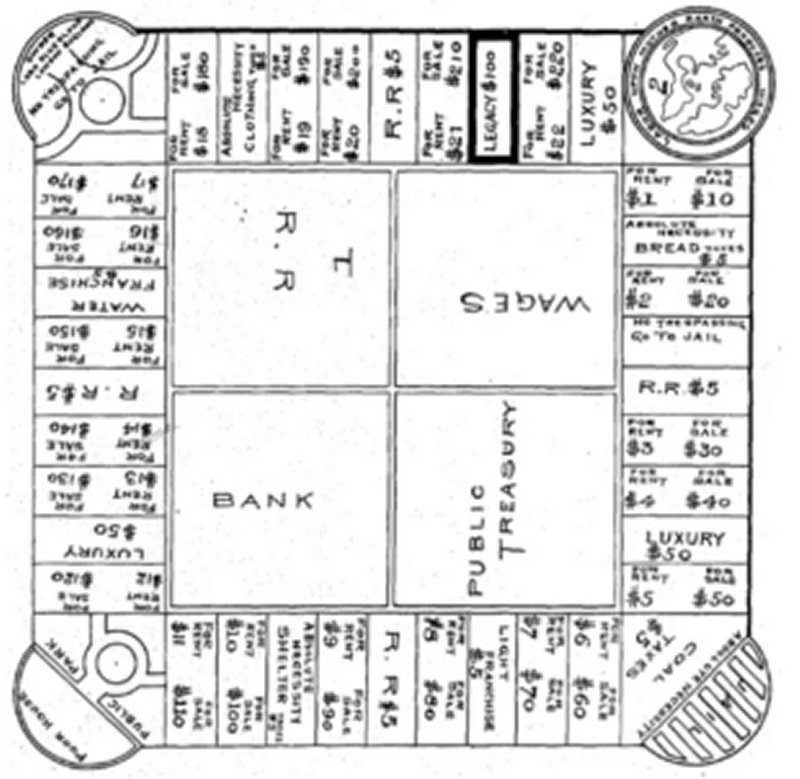

The Monopoly game's origins trace to stenographer Elizabeth ‘Lizzie’ Magie's The Landlord's Game, first patented in 1904. Despite countless Christmas Day games of Monopoly which end either in a family argument or boredom, Elizabeth Magie, who followed Henry George's teachings, had actually created it to “demonstrate Ricardo's Law of economic rent and Georgist principles regarding economic privilege and land value taxation”.

Family Monopoly arguments normally settle upon underhand dealings and accusations of collaboration, so perhaps Magie’s aim at exposing the evil heart of capitalism has hit home a tad.

The Landlord's Game was picked up by a Mr Charles Darrow thirty years later. He made a few tweaks and in 1934, Darrow first presented the game to Milton Bradley as Monopoly, claiming it as his own creation, but received a rejection.

He then approached Parker Brothers, who also dismissed it as “overly complex, technical and time-consuming”, sending their rejection on 19 October 1934.

The tale of '52 design errors' as Parker's reason for rejection was later exposed as fiction, forming part of the company's fabricated narrative about the game's creation.

Darrow made some changes though and resubmitted the game. Parker Brothers this time took up the idea and it became a runaway success during 1935.

A completely misleading narrative took hold claiming that Charles Darrow had invented the game. This inaccurate story appeared in Monopoly's own instruction manuals, a 1974 book about the game and continued to be cited in publications as late as 2007.

Lizzie Magie had patented her game in 1906, maintaining the patent until 1923 when she filed for a renewed version. She later sold her patent to Parker Brothers for $500 in 1935, as part of their strategy to acquire all rights to games resembling Monopoly.

Parker Brothers effectively created a monopoly on Monopoly itself.

Even though I’m happy to put the origin story right, I don’t feel that this is the place to comment on the various shenanigans involved with the American version.

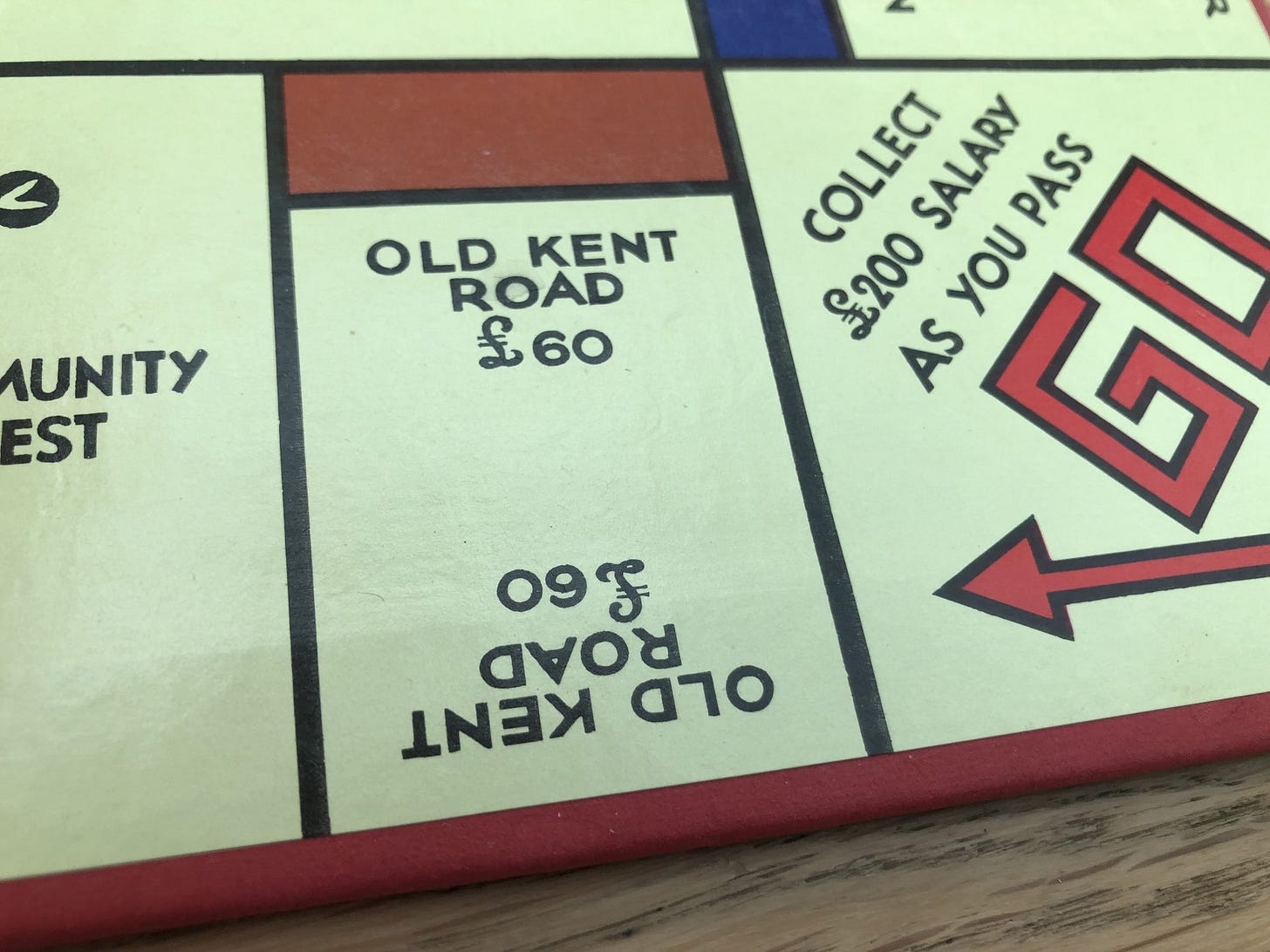

Waddington’s, a Leeds printing firm that had expanded into playing cards, sent their card game Lexicon to Parker Brothers seeking American licensing. In exchange, Parker Brothers in December 1935 forwarded Victor Watson Senior a copy of Monopoly.

After Watson and his son Norman played the game over a weekend, Waddington’s made an unprecedented transatlantic telephone call to Parker Brothers—the first either company had conducted.

This bold move secured Waddington’s the licensing rights for Europe and the British Commonwealth, except Canada. In 1936, they released their first board game: the British version of Monopoly, replacing Atlantic City locations with London streets.

As with the mysterious day trip to Spitalfields on Saturday 20 April 1912 by C.A. Mathew, the UK Monopoly board owes its origin to another day trip to London.

Victor Watson and his secretary Marjory Phillips travelled from Leeds to select suitable locations for the British board. They were back in Leeds the same evening. The US original had been based on Atlantic City in New Jersey.

Tim Moore's (author of the book ‘Do Not Pass Go’) research of Waddington’s archives revealed no clear rationale behind the selections.

But for what it’s worth, the light blue properties form part of the original New Road, which opened in 1756, running from Euston Road at King's Cross to Pentonville Road at Angel, Islington. The pink set's streets meet near Trafalgar Square, whilst the red set comprises streets along a route from St Paul’s Cathedral to Trafalgar Square. The orange set features locations linked to law enforcement and justice. The yellow set reflects entertainment venues, with Leicester Square known for cinema and theatre, Coventry Street for dining and clubs and Piccadilly for hotels. The green set represents retail and commercial areas. The purple properties - Park Lane and Mayfair - are the richest of all

The stations depicted the then London termini of the London and North Eastern Railway, with King's Cross serving Waddington’s base in Leeds. Pre-1947 boards showed 'LNER' on title deeds, changing to 'British Railways' after nationalisation. The LNER connection confirms why two obscure termini - Marylebone and Fenchurch Street - are on the London board whereas Euston and others aren’t.

Several American features remained unchanged: the police officer wears a New York Police Department cap rather than a Metropolitan Police helmet, the Free Parking car displays an uncommon British whitewall spare tyre and Community Chest refers to Depression-era American welfare support, unfamiliar in Britain.

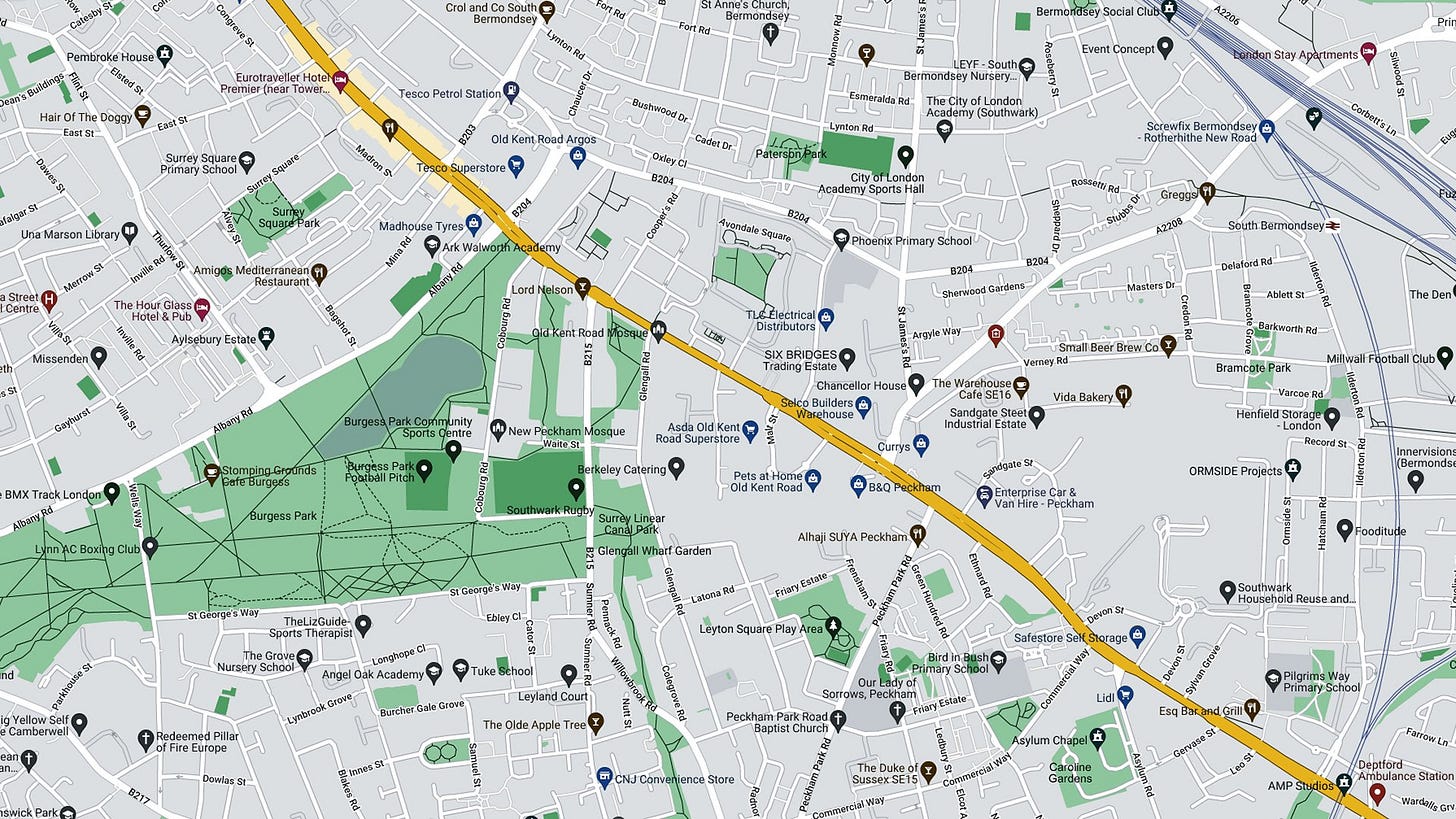

Being the sole location south of the River Thames, Old Kent Road stands unique amongst Monopoly's London properties. It is also distinctive as the only location situated beyond the Circle line's reach by more than one Underground stop. It is not close to any underground station. The nearest stop would be either Borough or Elephant & Castle - both still quite a hike. It is extremely unlikely that Watson and Phillips visited on that fateful day trip.

Taking a look at the Old Kent Road

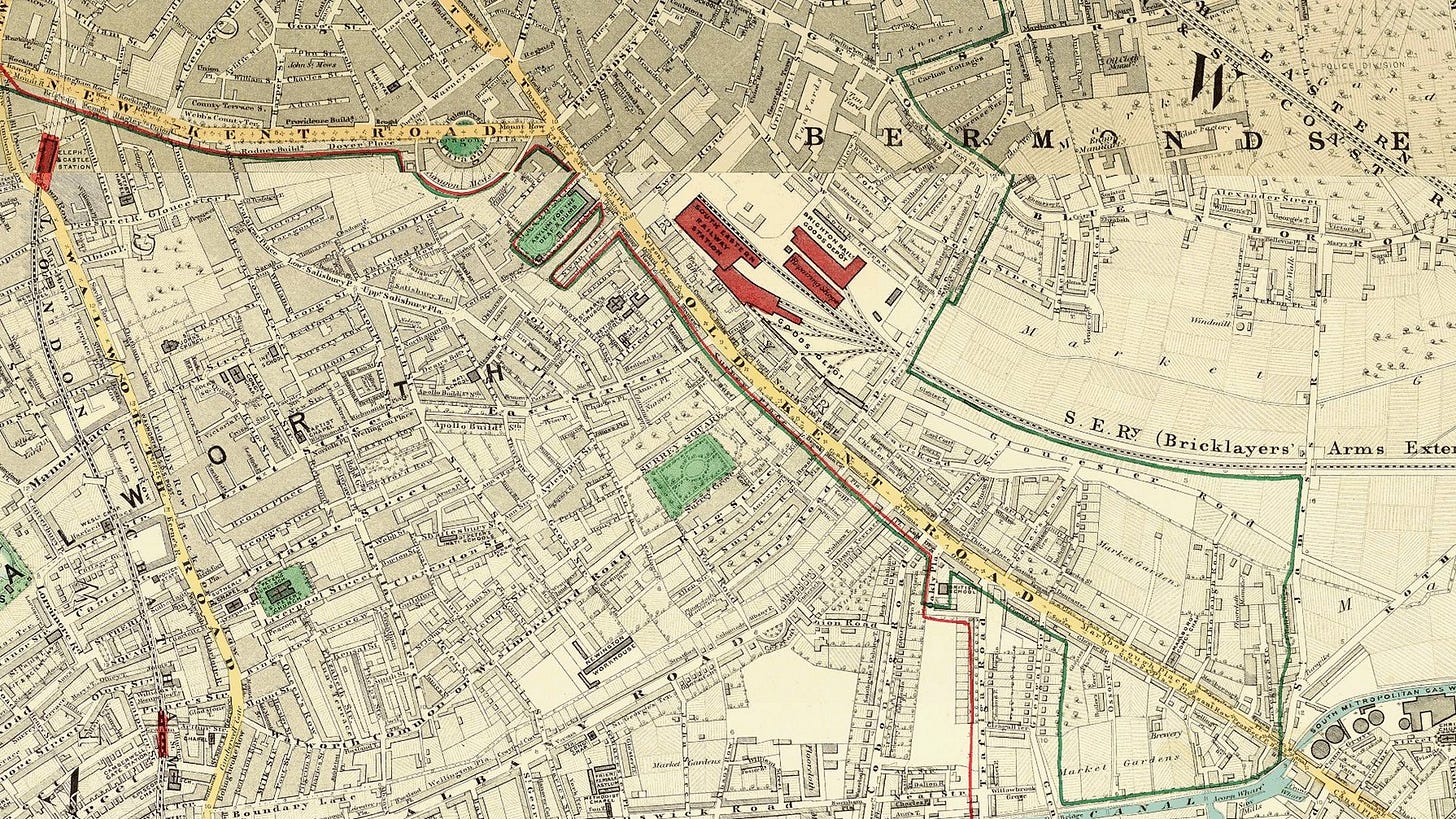

Old Kent Road stretches these days from the Bricklayers' Arms roundabout, where it meets New Kent Road, Tower Bridge Road and Great Dover Street, to New Cross Road. This change in name coincides with the Lewisham borough boundary, which marked the historical border between Surrey and Kent before the establishment of the London County Council.

This ancient trackway, first paved by Romans as the ‘Dover to Londinium road’ and later named Watling Street by Saxons, served as the path for Chaucer's pilgrims journeying from London and Southwark to Canterbury.

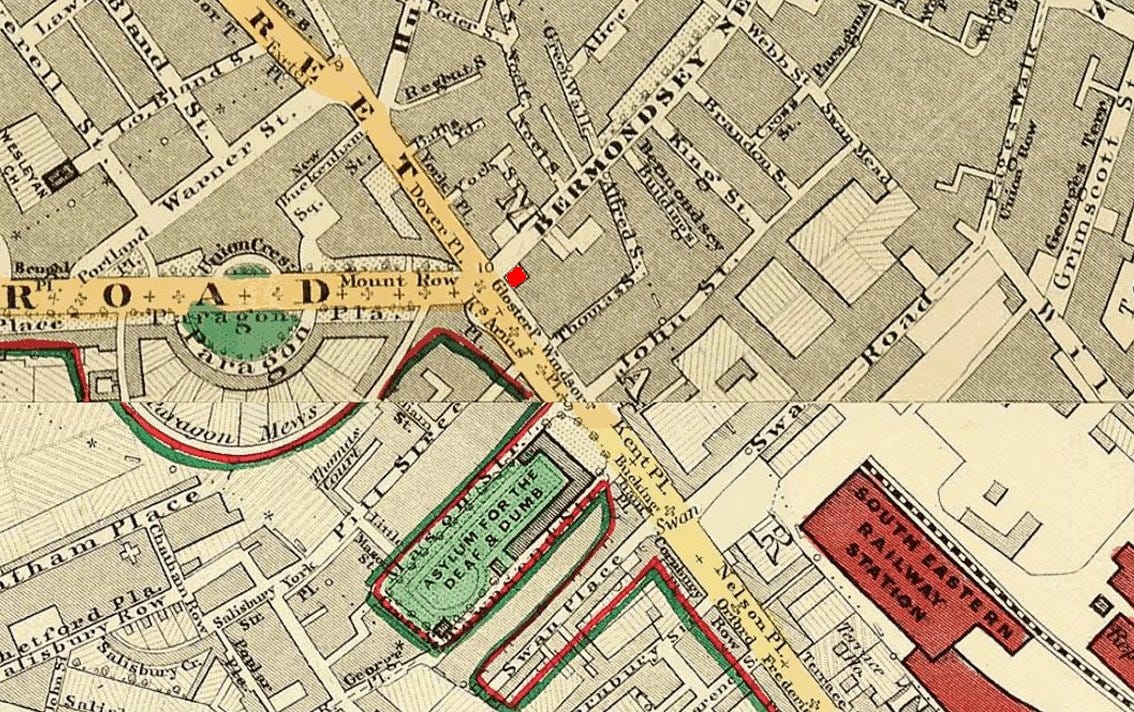

Since the 1750s-era Rocque map shows mostly fields and a single road, I’ll zoom in on the area with buildings just northwest of the red blob. Rocque should have placed the then-existing Bricklayers’ Arms pub on his map at the position of the blob but chose not to.

Along with the future site of the Bricklayers’ Arms red blob, we see two other inns and the Lock Hospital (later swept away) on what became Great Dover Street - the name for the road on the London side of the milestone to London Bridge.

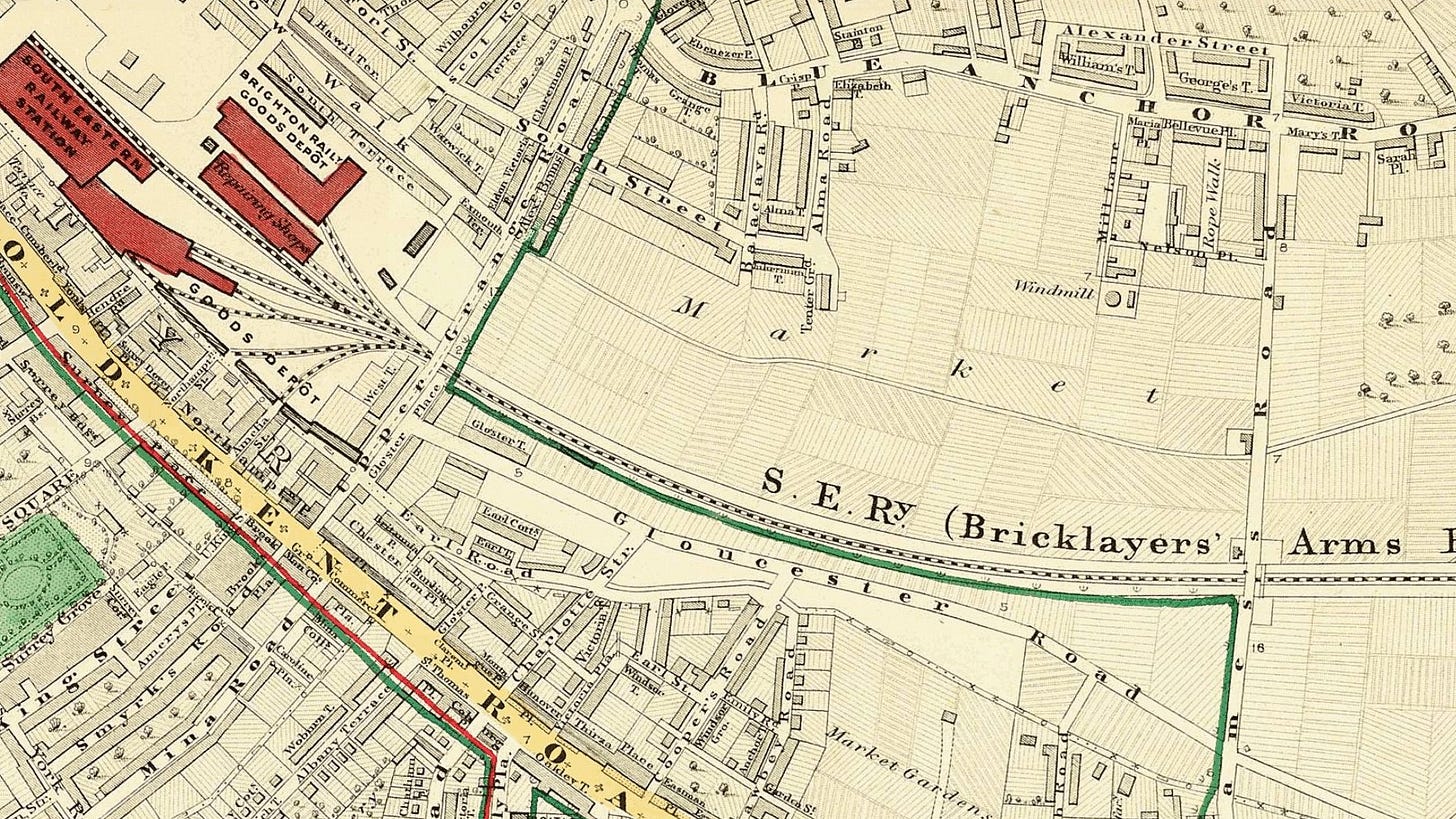

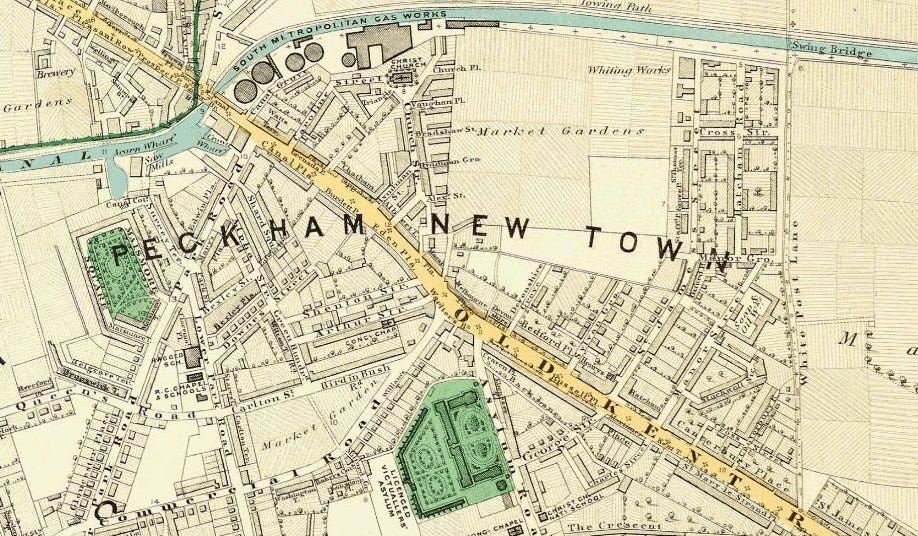

I’ll now continue with the 1860s era Stanford map on the same footprint as the first Google Map above. In the rest of this post, we’ll take a mid-Victorian walk along the Old Kent Road.

Time for an 1860s zoom in. We are at the top of Old Kent Road at the junction where the Bricklayers’ Arms roundabout will eventually wreck the scene. The diamond shape on the southeast quadrant of the 1860s junction (at Gloster P and highlighted by me in bright red) marks the original Bricklayers’ Arms pub which lent its name to lots of things.

The first street south on Old Kent Road is marked as Thomas Street. On this street stood St Thomas-a-Watering bridge, crossing a brook that marked the Archbishop of Canterbury's authority boundary over nearby Southwark and Walworth manors. The Thomas a Becket pub nearby references this connection. The site served as an execution ground, where criminals' bodies were displayed in gibbets along this main route to London. Religious dissenters faced burning or hanging, drawing and quartering here. Notable executions included Father Godson in 1540 for denying Henry VIII's supremacy, Welsh Protestant John Penry in 1593 and Catholics John Jones and John Rigby in 1598 and 1600 respectively.

From 1550, this point marked the City of London's jurisdiction, noted by a boundary stone in the old fire station wall.

A notable other building on the 1860s map is the Deaf & Dumb Asylum - a bit of a shocking name for our modern sensibilities.

There’s the ‘South Eastern Railway Station’ in a deeper red. Bricklayers Arms railway station opened in 1844, established by the London and Croydon Railway and South Eastern Railway as an alternative terminus to London Bridge. Located at the end of a short branch line from the main London Bridge route, it briefly served passengers before conversion to a goods station and engineering depot. The facility continued operating until its closure in 1981.

In the 1860s this conversion from passenger station to goods depot is underway.

Beyond the depot, this area was still market gardens in the 1860s. ‘Bermondsey as countryside’ is not so imaginable now.

South and parallel to the single rail track on the above map is Gloucester Road. This was renamed Rolls Road.

Post-Reformation, the Crown granted long leases to the Rolls family who controlled land from Bricklayers Arms to New Cross. They profited significantly from sub-letting during London's expansion, particularly through the 1750s residential developments in today's Surrey Square and the Paragon, designed by their surveyor Michael Searles.

By the 1870s, the family's wealth enabled them to acquire a Welsh castle and their political careers in Monmouth led to a peerage. They supported local London (well, Kent in those days) communities by providing land for social purposes, including the Wells Way library (now a youth club), Peabody Estate and St Saviour's Grammar School for Girls. Their legacy remains in Rolls Road's name and the 1750s White House between Peabody Estate buildings, which served as their home and later estate office until 1990, now a Pentecostal church. The last male heir, Charles Stewart Rolls, pioneered motoring and aviation, founding the partnership with Henry Royce.

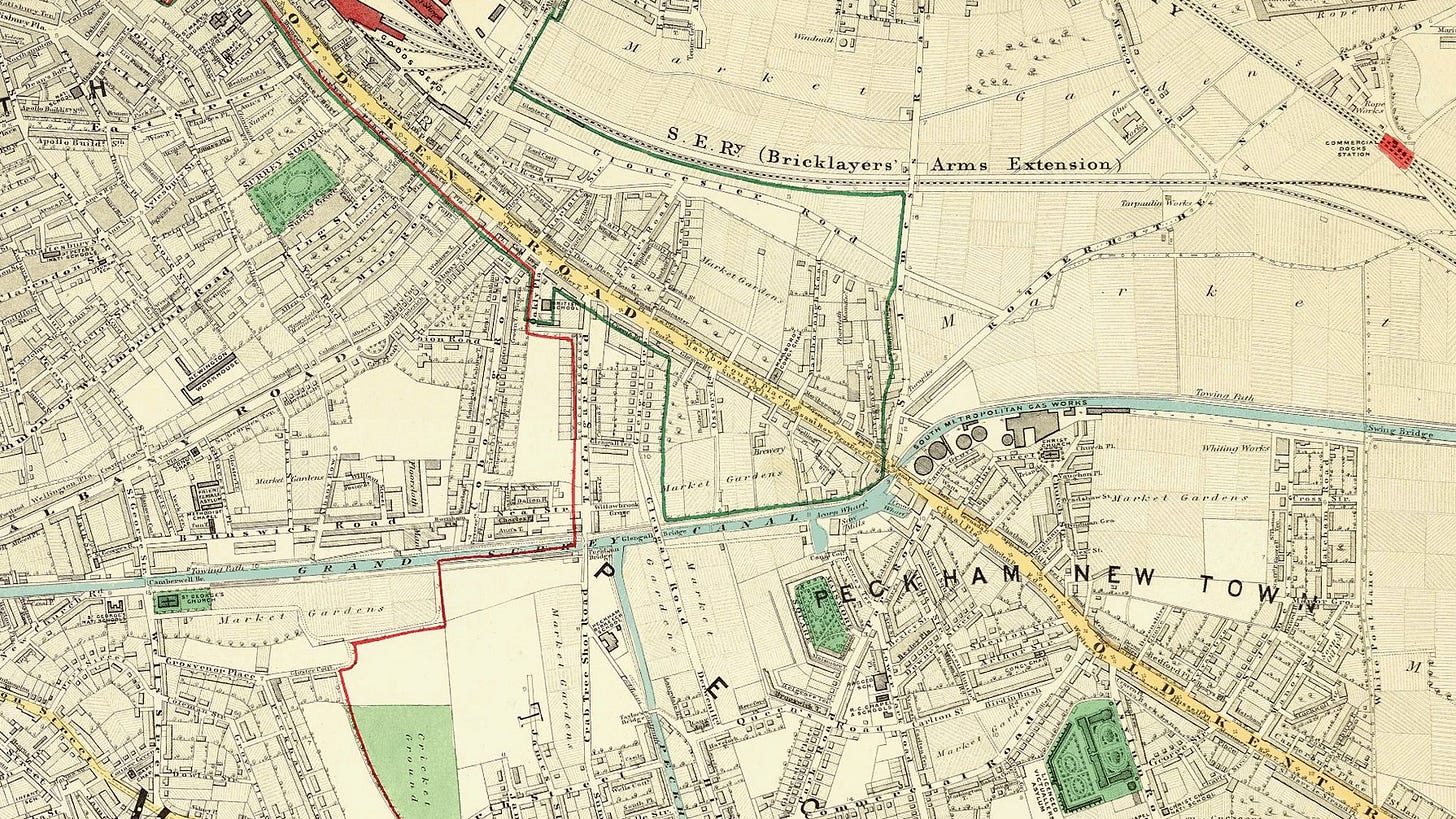

Moving south along the 1860s map, the Grand Surrey Canal crosses the scene.

The Grand Surrey Canal reached the Old Kent Road by 1807, extending to Camberwell in 1810 and Peckham in 1826. Its primary function was transporting timber from Surrey Commercial Docks and thence to the River Thames.

The canal's closure occurred in stages from the 1940s, with most sections, except Greenland Dock, shutting in the 1970s.

Today, the former canal route remains visible only in places.

In the 1960s the London County Council's 'Lungs for Londoners' scheme created new parks through urban clearance, including Burgess Park.

The final section of the Old Kent Road ends in New Cross but not before we encounter Peckham New Town. Building growth on land owned by the Hill family was driven by the Old Kent Road's influence. The Hill family's land became Peckham New Town, with the main road named Peckham Hill Road after them.

The arrival of public transport triggered a development wave. Horse trams in the 1870s and railways prompted widespread construction of more modest homes in available spaces. The Old Kent Road hinterland was filled in.

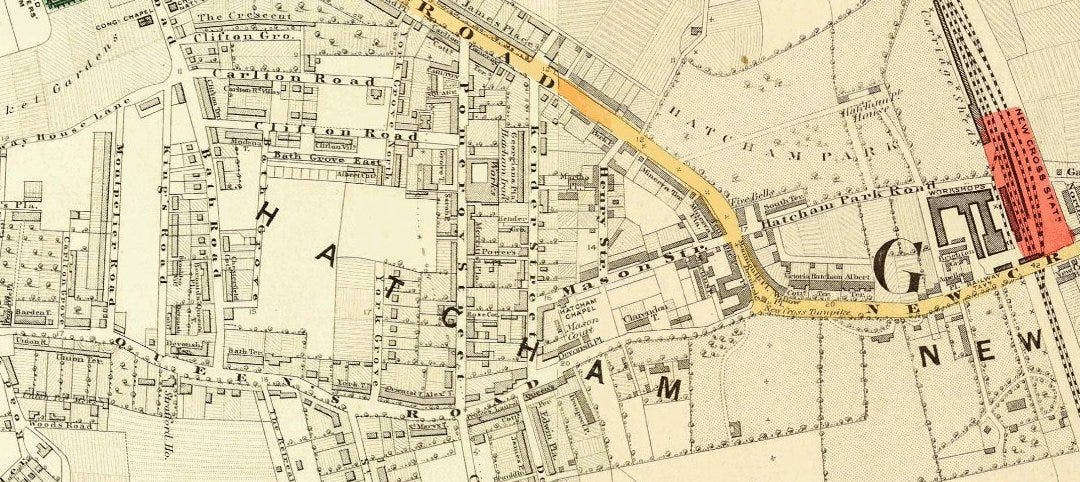

Further along in the 1860s, Old Kent Road encounters New Cross and ends here. But not before another nearly lost suburb name of London is passed. Few traces of the name Hatcham survive - though there’s a famous school: Haberdashers' Hatcham College. Until recently this was called Haberdashers' Aske's Hatcham College until it was demonstrated where benefactor Robert Aske's money had came from - the slave trade.

This concludes our 1860s trawl down the Old Kent Road. By far, the longest street on the Monopoly board of London.

NOTE: If you were following the recent 1852 map of London post, you may be interested that I have extended the zoom level of the map down to street level London-wide.

You can start on The Underground Map website on a road passed on the Old Kent Road tour, Commercial Way (click the link here) and then zoom in and out of the map to your heart’s content. Paid subscribers can download the map in the usual way by clicking Request this map.

What a read. Thankyou

Either you were reading my mind, or the Substack feed algorithm is more sophisticated than I thought https://open.substack.com/pub/gunnarmiller/p/secrets-of-the-worlds-greatest-investor .