Waterloo

The history book on the shelf is always repeating itself

In this post, we are going to take a historical deep-dive into the area around Waterloo station in a series of maps going back all the way until the 1750s when cows grazed where the station is now.

While this article will concentrate on particular features on each map, it’s worth perusing them afterwards - all sorts of things can be spotted.

You can ‘use your fingers’ to increase the zoom of each map on a mobile device but if you use a desktop computer to read this article, the maps will be clearer.

Before we begin the backtrack, let’s remind ourselves of the map of today’s Waterloo station and its surroundings.

Along this side of the River Thames, we see the South Bank area starting at Westminster Bridge which can be found at the bottom left of the map.

The South Bank stretches along the riverfront up to the rail lines of Hungerford Bridge and then beyond to the south side of Waterloo Bridge. The map is dominated by Waterloo station and its rail lines which stretch up from the bottom of the map. The right side of the map is greater Southwark and the top left shows Embankment station and the lines leading out of Charing Cross mainline station, across the Thames to Waterloo East and beyond.

Some recent developments include the arrival of the London Eye at the turn of the new millennium, the conversion of both County Hall and the Shell Centre into hotels and flats, the widening of Waterloo station to host new platforms in its role as the temporary London terminus of Eurostar, the Jubilee Gardens, and the Golden Jubilee Bridges crossing the Thames at Hungerford Bridge.

For our first historical map, we will rewind 70 years to the early 1950s. This map covers the same footprint as the modern map.

The landscape and street layout are still familiar although the Festival of Britain 1951 site is in full swing at the time of the map. It’s worth lingering on this wider view before we take a closer look:

Embankment underground station (top left) was still called “Charing Cross”

The future Eurostar platforms were just railway sidings west of Waterloo station

There’s a footbridge across York Road to connect the station with the Festival of Britain site

Waterloo East station is still named “Waterloo”

There’s a temporary Bailey Bridge south of Hungerford Bridge.

Closer in, there’s a lot to see. For bearings, County Hall is just off the bottom of the map behind the Power and Production Pavilion. The London Eye would be later attached to Nelson Pier. More pavilions surround the Dome of Discovery, built on the later site of Jubilee Gardens. Along the river, there’s a structure called the Skylon. Beyond Hungerford Bridge, the Royal Festival Hall has been built (opened 3 May 1951) and there are more pavilions and a shot tower.

The Festival of Britain was held in the summer of 1951, with the idea to commemorate the centennial of the Great Exhibition of 1851.

It didn't have international themes or even representation from the British Commonwealth. The 1951 festival exclusively focused on Britain and its achievements. The government aimed to use the festival to boost public morale by showcasing a successful recovery from the devastation of the Second World War. It aimed to promote British science, technology, industrial design, architecture and the arts.

The festival's main attraction was located on the South Bank of the Thames though other events took place in various locations around London (such as the Festival Pleasure Gardens at Battersea) and the wider UK.

The Festival of Britain became a symbol of transformation and garnered immense popularity. It played a significant role in reshaping British arts, crafts, designs, and sports for a generation.

The Exhibition pavilions comprised the Upstream Circuit, the Downstream Circuit and the Dome of Discovery.

The Upstream Circuit exhibits were designed to show off the modern Britain of the 1950s. Meanwhile, the Dome of Discovery and the surrounding exhibits focused on scientific discovery - both earthbound and in Outer Space (six years before the launch of Sputnik).

A notable feature was the Skylon.

The Skylon was a cigar-shaped tower covered in aluminium panels and supported by cables. It became a symbol of the Festival.

The architect's innovative design was made possible with the expertise of engineer Felix Samuely. The Skylon met an untimely end in 1952 when it was dismantled on the orders of Winston Churchill. He considered it a symbol of the previous Labour government and, as a result, it was demolished and sold for scrap after being toppled into the Thames.

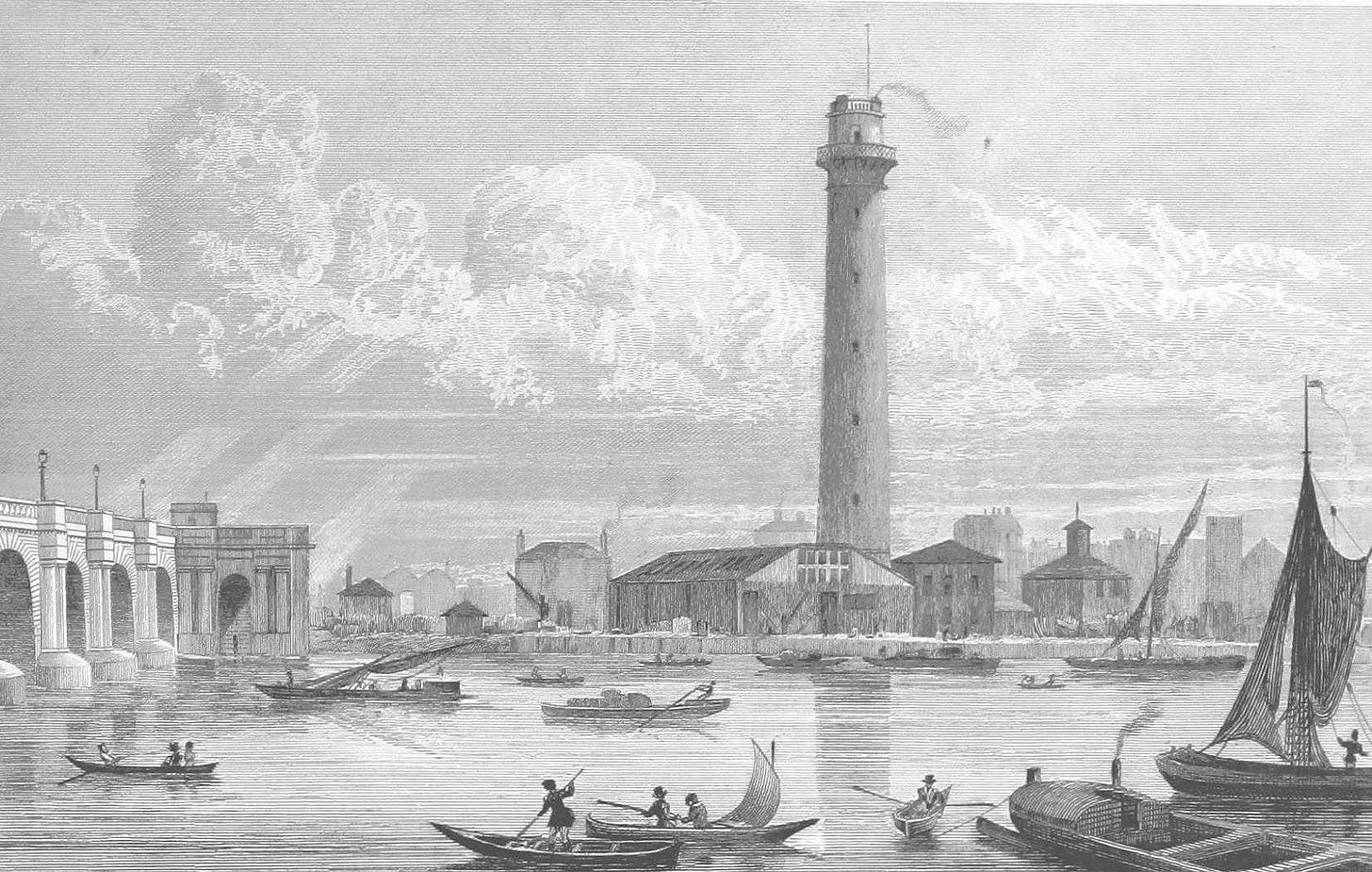

In front of the new Royal Festival Hall, a shot tower from the former industrial area located here was left in place.

The shot tower was constructed in 1826 and remained as a functioning facility as part of Lambeth Lead Works until 1949. It was a prominent landmark on the river and featured in a number of paintings, including one by J. M. W. Turner.

In 1950, a steel-framed superstructure was erected to serve as a radio beacon for the Festival.

The tower was demolished in 1962 to make way for the Queen Elizabeth Hall, which opened in 1967.

As the Festival of Britain drew to a close and the site redeveloped, the Waterloo Air Terminal repurposed the Festival Gate on York Road. Here you could check your luggage in and ride in a double-decker to Heathrow. 900,000 passengers used the terminal in the first year. The site closed in 1957 and was moved to West London.

Before we wind back in time once again, there’s something curious on the 1951 map and still visible today.

We are further focused on the entrance to Waterloo railway station. Mepham Street shown here is now the location of The Hole In The Wall pub. On the other side of the rails from Mepham Street are a series of streets in the process of being demolished in the 1950s: Boyce Street, Whichcote Street and Buckley Street. No trace of them exist now apart from the house at 5 Whichcote Street - you can see it on the map and also below.

For some reason, the house has survived from the early nineteenth century to this day but without its street.

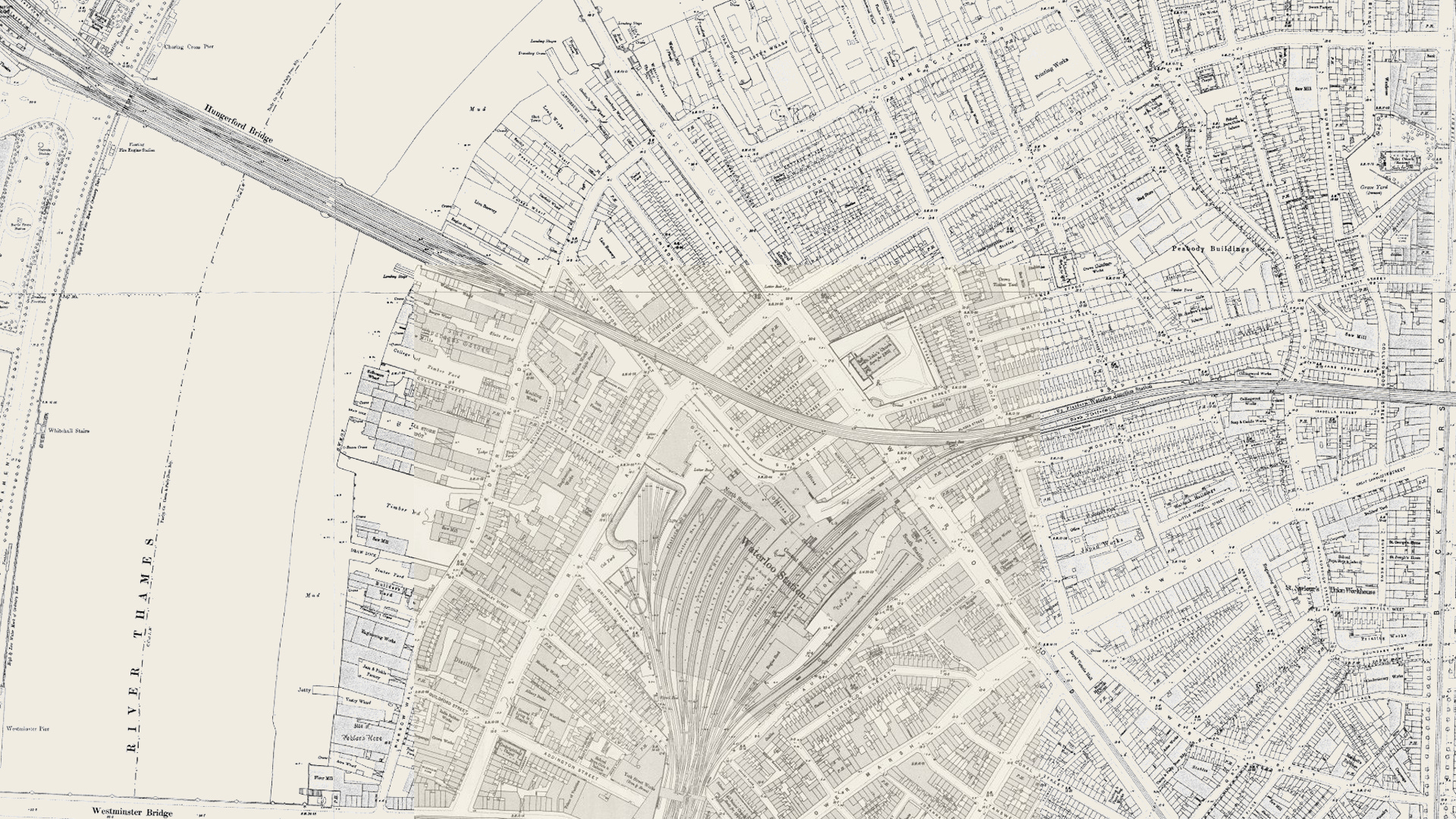

We are now going back to the Ordnance Survey map of 1898.

It’s on the same footprint as the 1951 and modern maps but it’s a little hard to process as there’s so much detail. So again we’ll zoom in.

There’s still a lot to take in but we can see the former streets of the Waterloo station area.

North of the station are the series of streets which were in the process of being demolished in 1951: Anne Street (called Boyce Street after 1939), Agnes Street (Whichcote Street until 1939) and Frances Street (later Buckley Street). These dated from the 1810s and contained terraced housing.

Waterloo station has a radically different layout at the end of the Victorian era. Mepham Street has a kink in it and the railway running through Platform 2 crosses Waterloo Road on a bridge to link up with Waterloo East. You can’t take this particular rail trip any more.

Across York Road from the station, there are old streets covering the future site of the Festival of Britain.

An old street called Vine Street leads west. The route of Vine Street follows the route of the pedestrian path beside the York Road entrance to Waterloo underground station.

In older days, Vine Street would reach a road called Belvedere Crescent, cross it, cross Belvedere Road and become College Street down to the Thames. College Street nowadays would mark the northern edge of Jubilee Gardens. The river frontage (slightly inland from the modern day) is a series of industrial sites, wharves and depots in 1900.

North of Hungerford Bridge is the Lion Brewery. Inland from there are yet more disappeared streets: Howley Place, Tenison Street and Sutton Street, all named after former Archbishops of Canterbury.

Winding the clock back to 1865, Edward Stanford produced a much clearer map. Yet again this is the same footprint as 1898, 1951 and 2023.

The railways lines out of Charing Cross are shown on this map. The first Hungerford Bridge though was designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and opened in 1845 as a suspension footbridge. It was named after the then existing Hungerford Market.

In 1859 the original bridge was bought by the railway company extending the South Eastern Railway into the newly opened Charing Cross railway station. The railway company replaced the suspension bridge with a structure designed by Sir John Hawkshaw, comprising nine spans made of wrought iron lattice girders, which opened in 1864. The chains from the older bridge were reused in Bristol's Clifton Suspension Bridge.

Buildings are not shown in as much detail on the 1860s map but the streetscape is very similar to 1898.

Waterloo station is a lot smaller. Mepham Street is called Vine Street which stretches under that name on either side of York Road. York Road is also named after an Archbishop. All the land hereabouts belonged to the Archbishop of Canterbury’s manor of Lambeth.

Most notable here is on the other side of the Thames, Bazalgette hasn’t yet completed the Victoria Embankment and Charing Cross station - recently built - juts out into the river.

Back we go some sixty years to 1799…

There’s always a view in London about how unrecognisable it is now compared to one’s youth. But the years between 1799 and 1865 was a case in point.

New bridges opened up Lambeth for building. Westminster Bridge though has yet to have an effect on urbanisation. Waterloo Bridge - like its battle - is yet to be.

There was not much demand for housing here if you couldn’t walk - before buses and trains - to your workplace. Without a Waterloo Bridge, there’s no easy way to get over the river to the London bank.

While the riverfront is still yards and wharves, inland it’s fields. Along Vine Street - a rural thoroughfare - is the Belvedere Brewery built on the future site of Waterloo station. Also tucked away amid the fields is a vinegar factory to its north - kept away from the noses of too many people.

The future Belvedere Road is called Narrow Wall - a route on the line of the old earth embankment of the River Thames.

By the 16th century, the foreshore was covered in rushes and willows, but it was prone to frequent flooding at high tide. This land was regarded as "waste" belonging to the manor of Lambeth, hence the property of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Much of the land was leased in the early 18th century to Sir William East. After this time, it was described as a wall with all the properties on or near the wall being used as timber yards and wharves.

In the early nineteenth century, the road was straightened with the straight section becoming Belvedere Road and the former kink retained as Belvedere Crescent.

We’ll end our trip through the ages with the map of the area from one of the most famous mapmakers of London - John Rocque.

John Rocque’s Lambeth is quite similar to the later 1799 version. Cupar’s Gardens might have been a lot more pleasant than the vinegar manufactory which replaced it.

There is a tenter ground toward the top right - an area used for drying newly manufactured cloth after fulling. The wet cloth was hooked onto frames and stretched taut using tenterhooks so that the cloth would dry flat and square.

With this, our journey through time in Waterloo is at an end.

There’s an accompanying video which tells this story in another way….