Tudor London's involuntary Green Belt

How a lost London river stopped early urbanisation to the north

Unless you live or work in the area, the districts immediately to the north of the City of London are lesser known than those to the east and west. The West End and the East End can almost be said to be famous worldwide - Whitechapel, Westminster, Kensington and Spitalfields.

But go north and things - even to Londoners - can be a bit indistinct. Clerkenwell - now where’s that again? Somewhere near Farringdon? Finsbury? How does that relate to Finsbury Park?

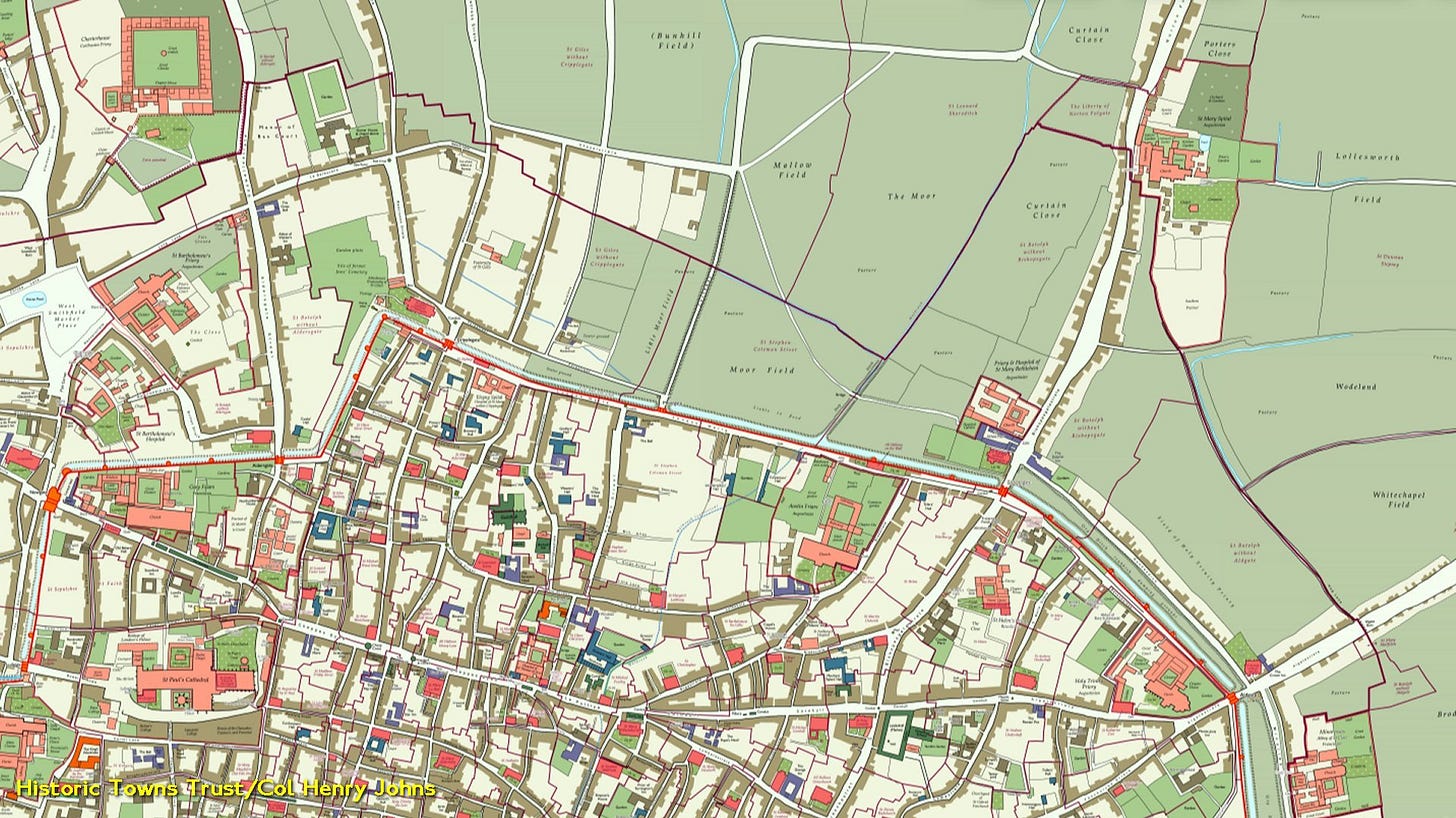

Perhaps one of the reasons for this is that the area to the north remained undeveloped for a long time. From Roman London days until the sixteenth century, the London Wall marked the northern edge of urban London. Beyond it lay a huge marsh called Moorfields.

Moorfields was described by an early Londoner called William Fitzstephen as the "great fen which washed against the northern wall of the City".

London Wall was a physical wall in earlier times and, between modern Moorgate station and modern Liverpool Street station, there was an opening in this wall to allow the River Walbrook to flow through an arch and into the City.

I’m not going to tell the tale of the River Walbrook here. It is a long lost river of London and deserves its own article. The Walbrook rose in the Shoreditch area, ran in open country until it reached the arch in London Wall and then flowed between the two main hills of the city: Ludgate Hill to the west and Cornhill to the east. It then reached the Thames. Once it entered the City it was treated as a sewer and, well before Tudor times, was bricked over as a result.

The opening in London Wall was built just a little too narrow for the flow of the Walbrook. It was effectively a dam, causing the river to flood the area north of the wall making it boggy.

While the term ‘moor’ in its broody Wuthering Heights sense indicates (according to the dictionary) "a tract of open, untilled, more or less elevated ground, often overrun with heath", the origins of the word lie with the Old English mor: "morass, swamp".

In Southern English placename usage, moor is less ‘Heathcliff’ and rather indicates a wetland, such as in Sedgemoor in Somerset.

And here on the London fringes, the term was also used in the ‘marshy’ sense - Moorfields covered the area north of the London Wall - the human-caused floodplain of the River Walbrook.

Many gates of London were Roman-built. But Moorgate was, much later, the last to be constructed and took its name from the adjacent Moorfields. At first it was simply a gap in the wall. A causeway was run north over the marsh from Moorgate in the 15th or 16th century. Little Moorfields became the name for the open land west of the causeway.

The gate of Moorgate was demolished in 1762 and finally gave its name to a major street, Moorgate, laid out as late as 1834, and to a station in 1865.

Moorfields was contiguous with Finsbury Fields, Bunhill Fields and other open spaces. The fields were divided into four areas; the Little Moorfields, Moorfields proper, Middle Moorfields and Upper Moorfields.

When a marsh was underpinned by certain stickier soils such as clay, it is known also as a fen. Moorfields was the term for an area of this local fen which in its larger sense covered much of the ancient Manor of Finsbury. It is suggested that it extended west from the Walbrook, to the vicinity of Old Street in the north, and the road from Cripplegate in the west.

Finsbury’s name likely derives from the ‘settlement beside the fen’. (Disclaimer: The Wikipedia has the derivation as "the manor of a man called Finn"). As I’m declining here to relate the full story of the Walbrook, I’m also going to fail to pursue why London has both a Finsbury and a Finsbury Park in two completely different places.

Whereas London slowly spread to the west and the east, the marshy conditions of Moorfields hindered urbanisation to the north for over 1000 years after the departure of the Romans.

Sheer population pressure caused a decision to be made to culvert the Walbrook outside the city wall to mitigate the restrictions caused by the marsh. By the 1600s, the entire length of the river was flowing underground.

The great fen as a result began to dry out from the outside in, freeing building land first along Bishopsgate towards Shoreditch and then along Bunhill Row towards Clerkenwell.

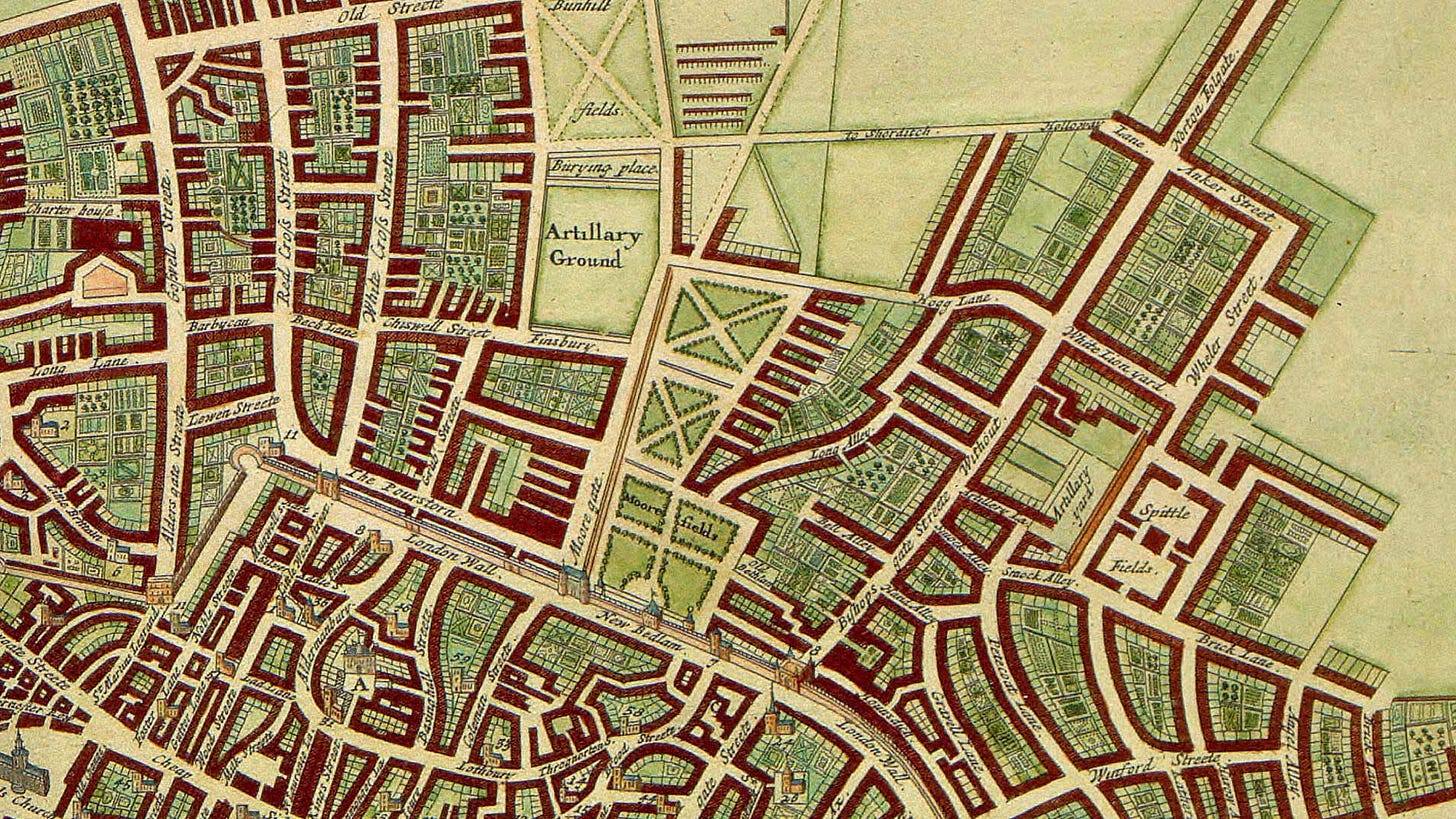

Moorfields became a lozenge of open land connecting Moorgate to the countryside but increasingly surrounded by building.

This 1690 map shows this. The three green spaces with cross shapes are (Lower) Moorfields, Middle Moorfields and Upper Moorfields. Little Moorfields to their west had gone by then.

Though not clearly shown on the map above, from 1676 to 1815 the Bethlem Hospital lay on the southern flank of Moorfields proper.

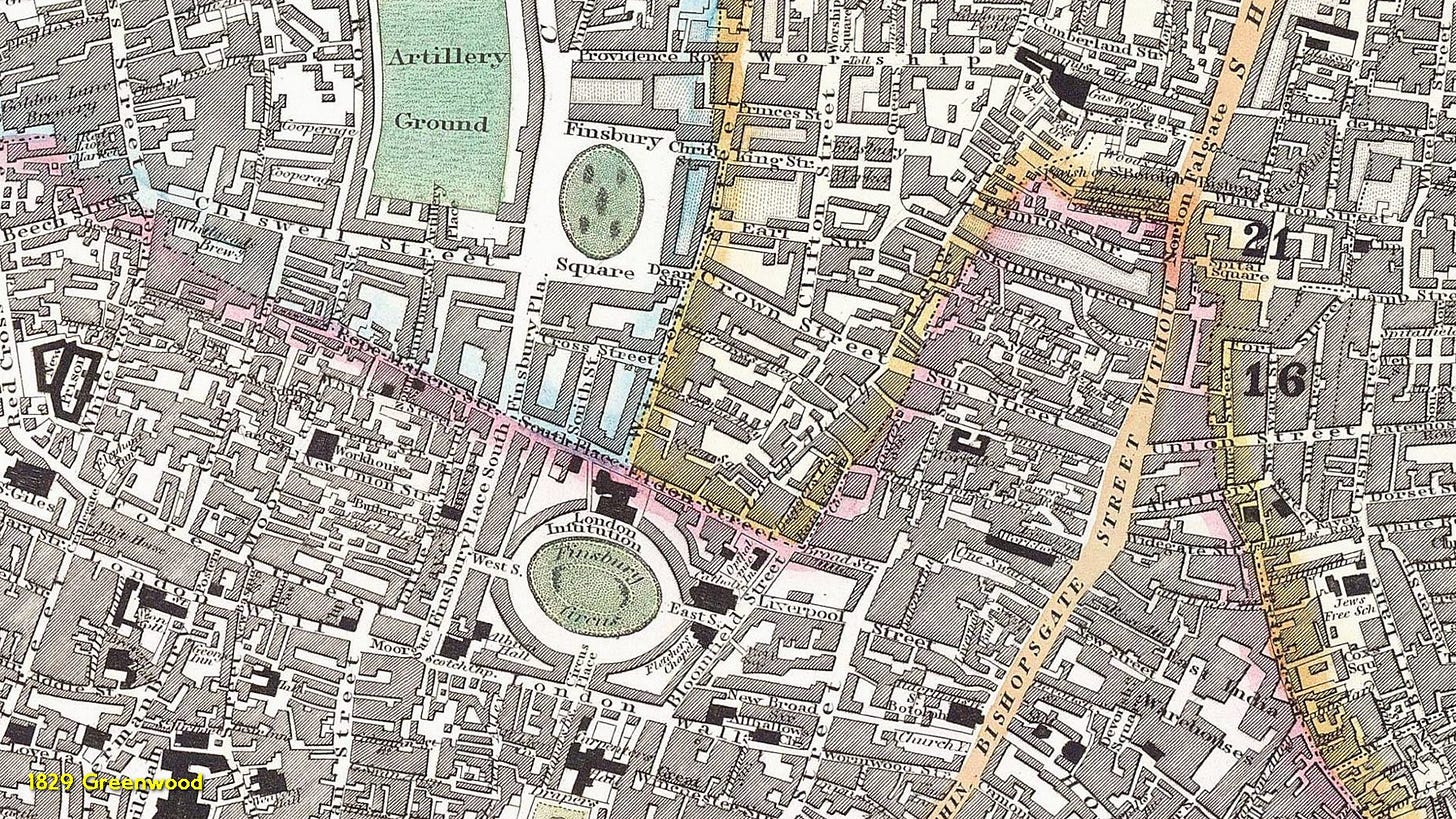

The John Rocque map published around 1750 is quite a marvellous map with a lot of eighteenth-century detail. But notable here is the further urban expansion of the built area squeezing the three Moorfields.

By the turn of the nineteenth century, Finsbury Square and other new roads had put paid to the northernmost two Moorfields as the new suburb of Finsbury continued to develop.

By the 1830s, the southern Moorfields and its hospital had disappeared too. Finsbury Circus replaced them both in 1812.

The early, involuntary ‘green belt’ formed by the Walbrook and its marsh was finally gone and London had spread north.

As is customary, I made a video of all this which can be accessed below.