London's countryside mapped

A map surveyed in the last decade of the eighteenth century captured every field

At time of writing this post, the Queen’s Tennis tournament is taking place in London W14. In a roundabout way, this time last year, also to coincide with the tennis, I wrote about it.

While researching for my walk between Barons Court and West Kensington stations, I had discovered the surprising history of a single carrot field which produced two internationally famous sports clubs at the top of their game - the Queen’s Club (tennis) and Fulham FC (football - the soccer sort of football).

The video at the bottom discusses this lucky field of carrots. Not strawberries - carrots.

A certain Sir William Palliser had owned all the land around the future Barons Court station. Before he came into its ownership, there had been an agricultural revolution in the late eighteenth century. Common land and strip farming were turned over to larger privately-owned fields. Many impoverished rural workers being deprived of their common rights flocked to the cities where the new factories needed employees.

The loss of this common land and the rights which went with it is one of those painful cultural changes which can be often glossed over by historians. In this case, the sudden conversion of workers from rural to urban jobs helped fuel the Industrial Revolution. It emptied a lot of the countryside and meant that towns and suburbs were thrust suddenly into existence. The Industrial Revolution story is a lot ‘sexier’ than rural poverty.

All sides of my own family moved to the new suburb of North Kensington and adjacent Kensal Town soon after it came into being in the 1860s. It was fields before that and, in parallel, my family hailed for generations before the 1860s, in many scattered villages and not from London at all. Let’s face it - few of us are from true London families going back generations. We are nearly all incomers.

All you need to do using Ancestry and other genealogical websites is to find a forebear, and if UK-based, see which village they came from and then see how their own forebears came from the same village for generations before the brave one who decided to move to the city. I need to visit Burwash in Sussex some day - I have hundreds of ancestors there.

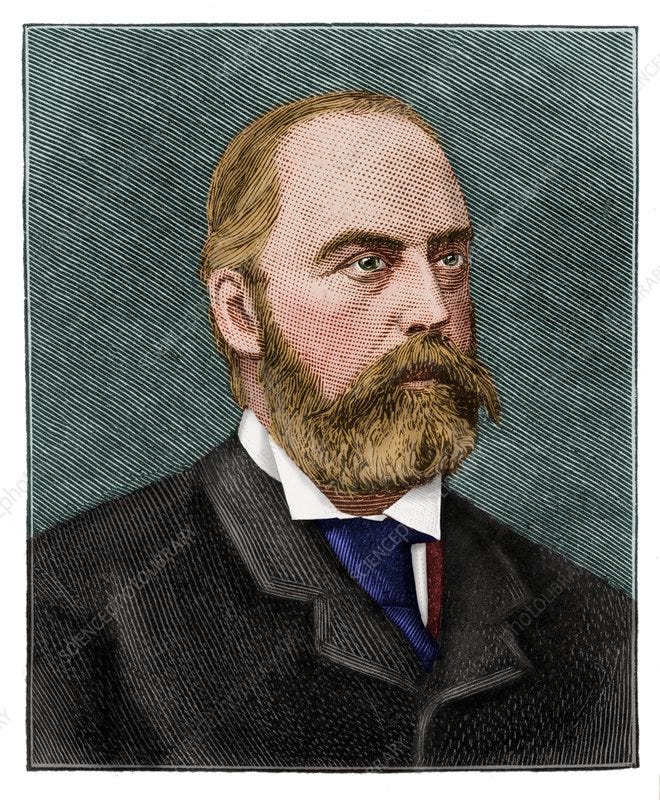

Sir William Palliser was an Irish-born MP who represented Taunton in Somerset. He was quite a guy apparently, inventing and patenting a lot of military ordnance. But, happily for him, he became quite wealthy and bought fields west of a scattered Middlesex village called North End . Even happier for him, he acquired his land at just the right time.

The (Metropolitan) District Railway was beginning to plough its way west through the area and Sir William named his estate Barons Court. It was probably called after a large house called Baronscourt in County Tyrone, and thus inherited the lack of an apostrophe which has annoyed many Londoners since.

The naming choice may have been influenced by nearby Earl’s Court.

But the land had been so rural that it didn’t have a name or a village centre before Sir William came along.

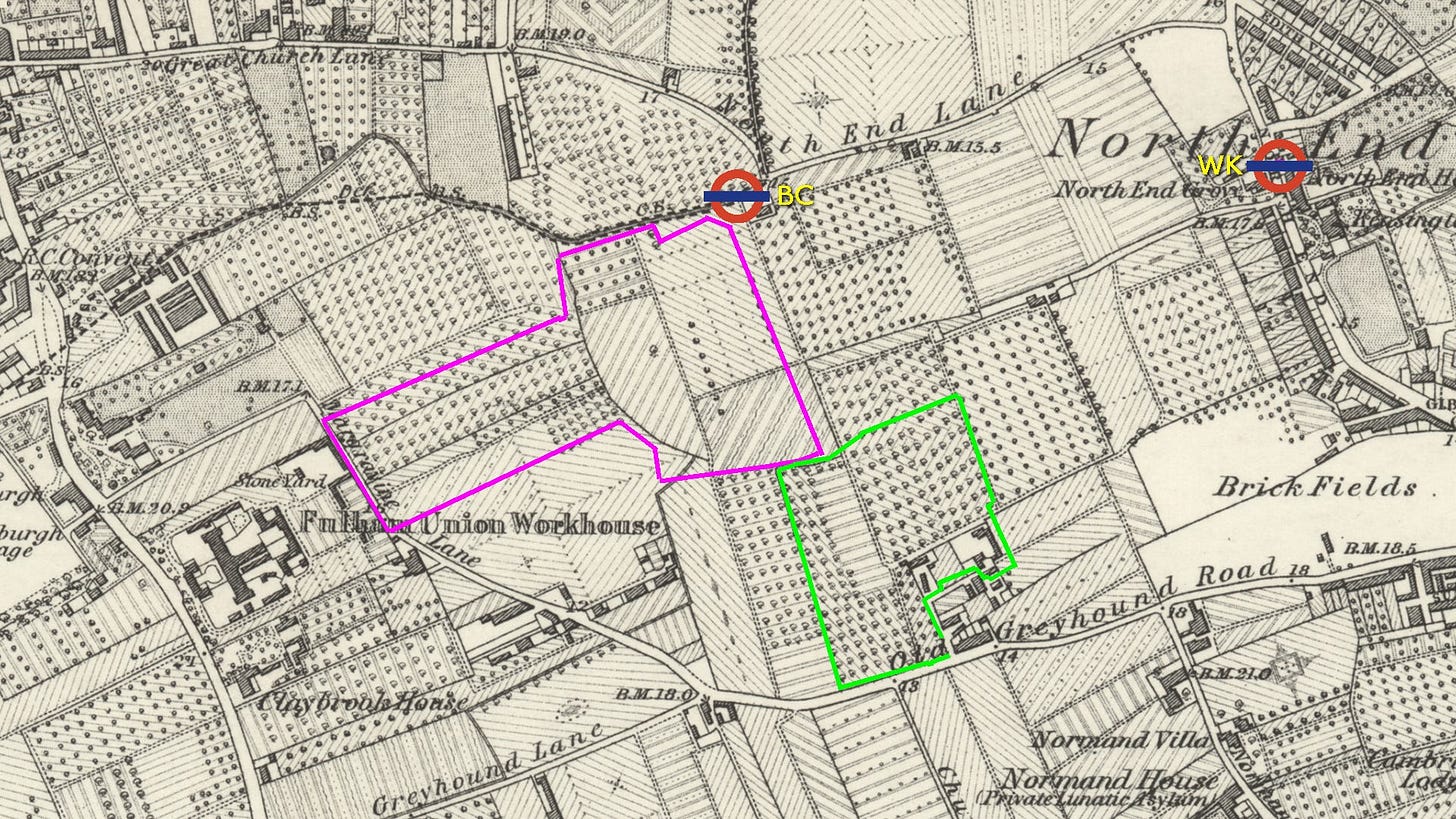

The map below dates from the 1860s and shows all the cabbages, carrot fields and orchards in dotted patterns.

Sir William Palliser turned nearly all his land over to developers and named many of the new roads after himself and his family.

He saved two pieces of land for other uses - the purple-outlined area became Margravine (Hammersmith) Cemetery. And the carrot field called Queen’s Field (outlined in green) had been leased by a cricket club and Palliser continued to honour the lease.

I have marked the future site of Barons Court station (BC) - roughly in the middle of nowhere at first. And in North End village there’s a new station called West Kensington (WK).

This area became known as 'West Kensington' during the 1880s at the request of its developers Gibbs and Flew who were having trouble selling their newly-built houses in a Fulham backwater. West Kensington station on the Metropolitan District Railway was originally called 'Fulham - North End'. Interesting to note that this new suburb was neither in Kensington nor in any sense west of it.

But let’s move back 70 years.

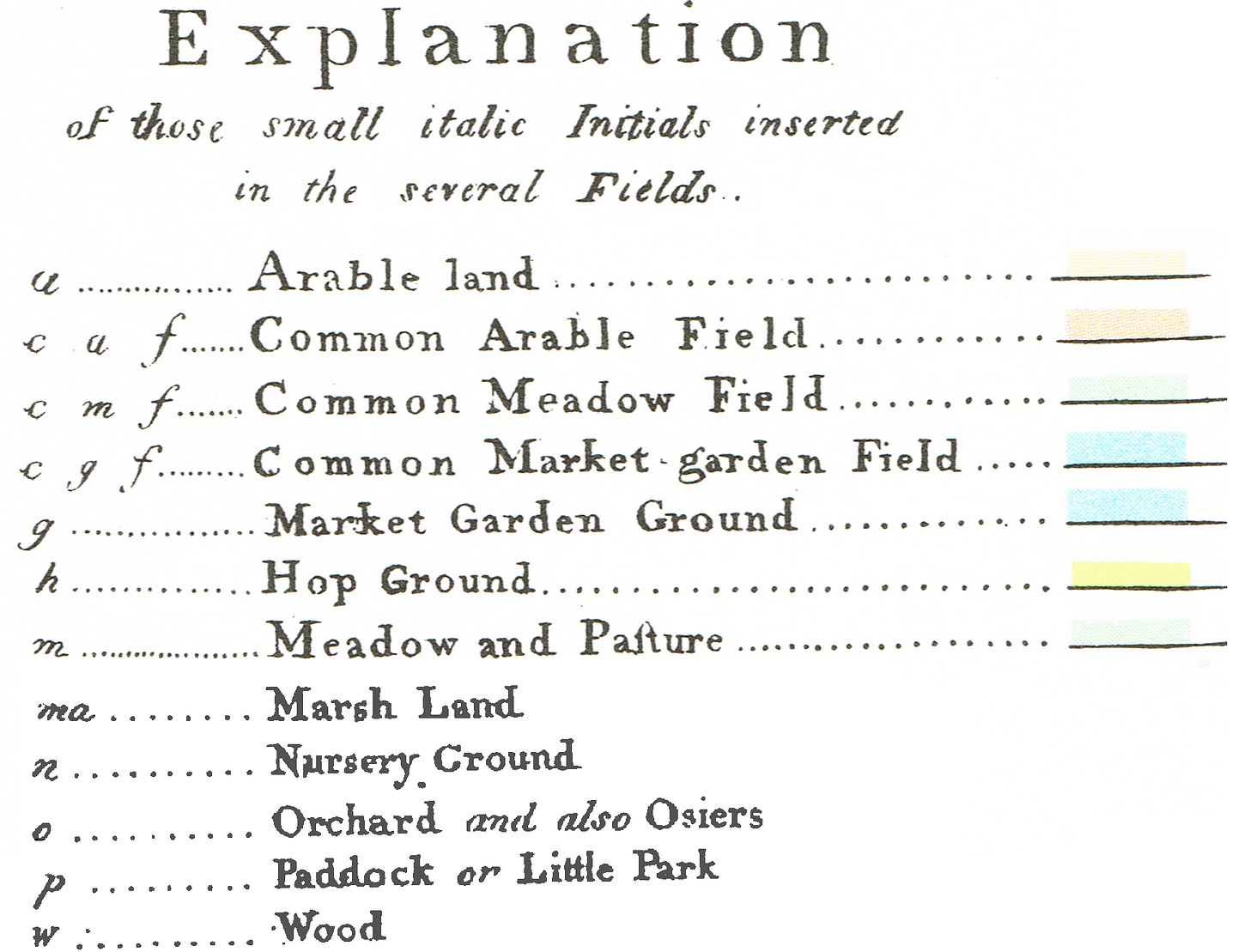

In 1800, Thomas Milne published his land use map of Middlesex, north Surrey, north Kent and west Essex.

It bears the full title ‘Milne's Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster, circumjacent Towns and Parishes Etc. laid down from a Trigonometrical Survey taken in the Years 1795-9’ which is quite an eighteenth century mouthful of a title.

The map is hand-coloured and engraved, with watercolour washes. Each sheet bears Milne's signature and a serial number, and it's extremely rare - only one complete copy of all six sheets survives.

The complete map was published on 11 March 1800, and created at a scale of two inches to a mile, engraved on six plates covering approximately 260 square miles extending from the Harrow Weald to Woodford and from Hampton-on-Thames to Sundridge Park.

It had been a mammoth undertaking. The map represents the first true land utilisation map and is considered ground-breaking in the field of cartography. It anticipated by more than a century and a half the use of key letters and colours for mapping land use. This was probably the first map of the London area showing how fields were used for different crops.

Milne's map was one of the first to make use of a precisely-surveyed triangulation system and one of the first land use maps to use symbols rather than crude and often unexplained illustrations. Thomas Milne was an experienced surveyor and member of the Society of Civil Engineers, with a contemporary calling him "one of the most able and expert surveyors of the present day" with special aptitude in using a light theodolite for mapping.

This map provides invaluable insight into the London area's landscape at a crucial period of development, documenting the agricultural hinterland that surrounded the growing metropolis before the massive expansion of the Victorian era.

Let’s take a look at his key. If you went off to read my previous post, I’ll shamelessly reuse some of my text from there:

Three extra categories were needed for Milne’s map compared to any modern landuse map: Common Arable Field, Common Meadow Field and Common Market Garden Field. This was to depict the common land to which locals had had joint rights to use and exploit.

As enclosure continued, Milne was using fewer symbols on his maps for common land in agricultural use. As the nineteenth century wore on, common land which wasn’t reassigned to owners became large public parks - especially in the area which became south London. While there is Ealing Common and a few others north of the Thames, Clapham Common, Wandsworth Common, Wimbledon Common and many more abound in the south.

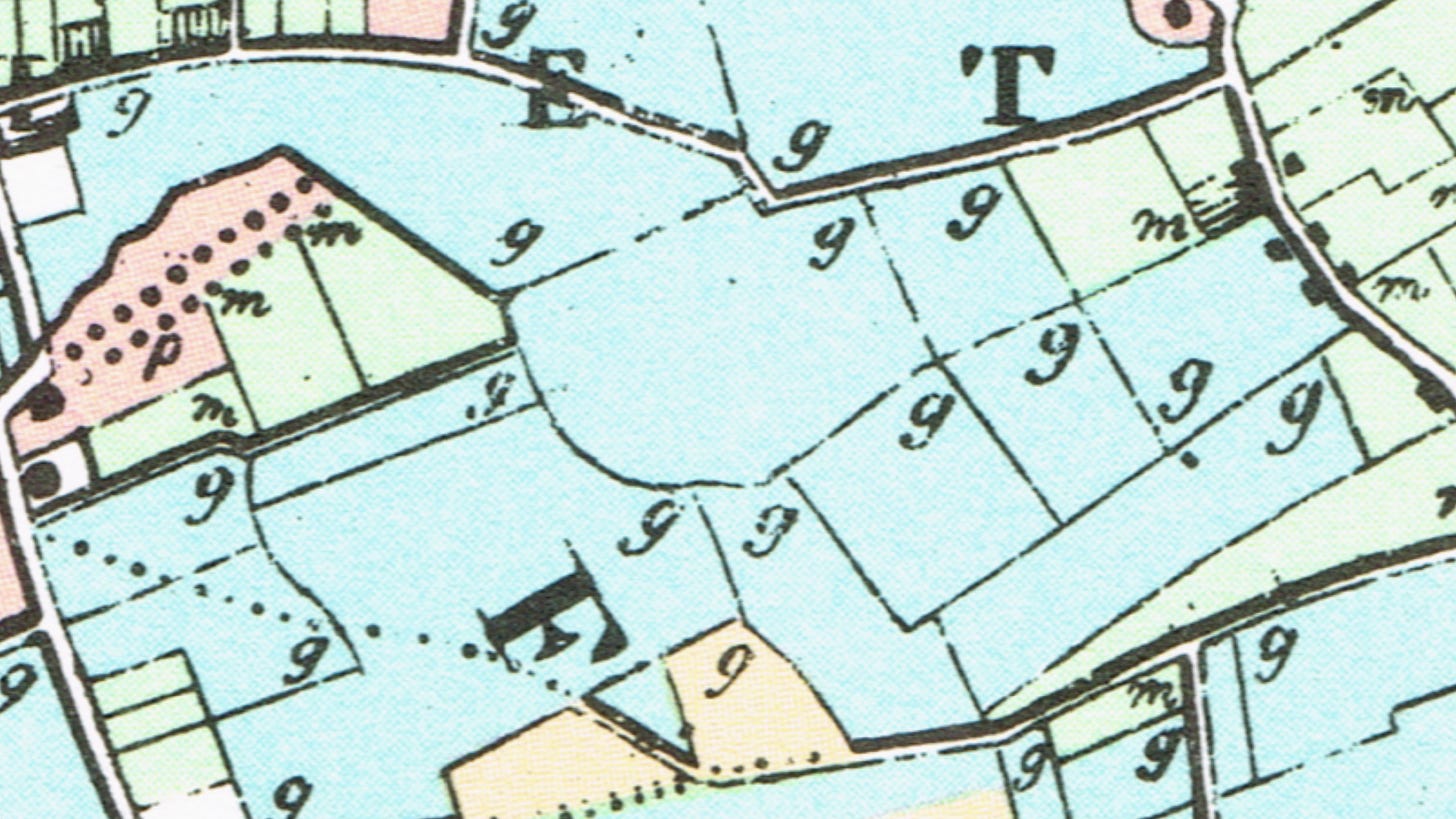

We were looking at Barons Court and here is Milne’s map of the area dating from 1800. This is on the same footprint as the first map, and a lot clearer.

The m of meadow is outnumbered by the g of market gardens. London is quite far by horse and carriage and thus the arrival of large villas has not occurred - only one p. Once transport improves, there will be a trend for the richer folk to work in the City and weekend in the countryside in luxurious houses. Some of that attractive countryside is here in Barons Court.

Milnes map is a snapshot of a changing London area. The future London W14 had completed the enclosure process. Hampton and Teddington (below) reflects the previous state of affairs with the c a f markings

Milnes map is truly fascinating for amateur historians such as me.

While I’m still here but having completed the writing, there are paid Substack subscriptions. I think my tomes for the while will stay free but you can support my work. There are extra benefits for paid subscribers. On www.theunderground.com, you can download unlimited, print-quality old maps of London, such as the entire 1800 Milne map. I have other benefits in the pipeline too.

The video version of this article features here:

NOTES:

Just to be precise - I didn’t want to break the narrative with exceptions but “All sides of my own family” was used in a loose sense as my maternal grandmother hailed from Bow, East London. But the rest of the family did come from North Ken.

Just to be finickity, the Queen’s Club carrot field wasn’t necessarily carrot-specialised. Cabbages, apple trees and potatoes are other possibilities. And indeed strawberries to match the tennis.

Really enjoying these fascinating psychogeographical and sociohistorical walks. Thank you.