The very first movie made in London was a one-off in 1891, by a man called William Friese-Greene using a camera of his own invention. He placed the camera on the pavement outside 39 Kings Road in Chelsea and filmed a few seconds of moving images of passers-by.

This is thought to be the earliest depiction of London on moving film. A box of negatives of this short movie was discovered in Paris about a century later and this sequence was reconstructed.

The lineage of London filmmaking however goes back further to 1888, and not in London but in New York City.

Thomas Edison employed a Scottish assistant called William Dickson and they began looking around at the then French pioneers of movie making and decided to get into the business themselves.

The pair set out to create a device that could record moving pictures, and in 1890 Dickson unveiled the Kinetograph - a motion picture camera.

Edison was quite savvy and knew that making money out of this was probably a good idea. Unless an audience could see a finished film, they couldn't generate a lot of income.

Edison and Dickson in 1892 announced the invention of the Kinetoscope. This was a machine which could project the moving images onto a screen, and they began to show movies on this device in 1894.

By 1896, a mini boom had started amongst London filmmakers as they produced material for the new ‘Kinetograph parlours’ using Edison and Dickson's 35 millimetre camera.

Alongside William Dickson there was another notable London film pioneer who actually lived in the metropolis. He was a Muswell Hill lad and his name was Robert W. Paul. He was originally an engineer. Like Edison and he was also pretty savvy with money - quick to grasp the commercial potential of cinema.

He knew a mechanic called Bert Acres. Together they designed a camera on which to shoot films. They also designed Britain's first indigenous projector - the Animatograph - with which to screen them.

Robert Paul’s big break came along in 1897. Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee celebrations took place that June and Paul was one of six crews to film the event - each of them paying large sums of money to secure good filming positions amongst the estimated crowd of three million onlookers.

Once finished, Paul released the film as 12 separate titles, each of which was sold for 30 shillings to distributors.

Early movies were printed onto nitrate. This is an organic volatile material and so few of the early movies have survived.

The 1890s was a decade of rapid innovation.

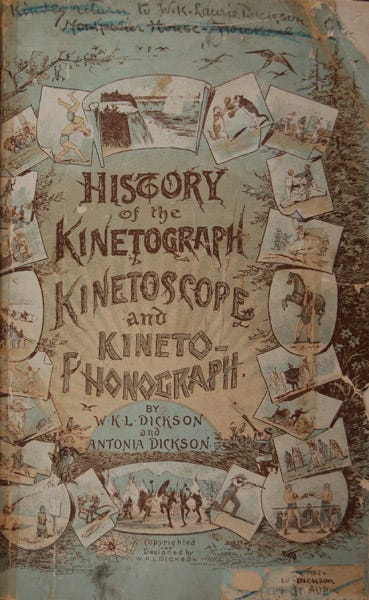

William Kennedy Dickson, who had created the Kinetograph, left the Edison company and because of Edison's 35 millimetre patent, had to reinvent a process that he had already invented. He was aided in this by his sister Antonia.

One of the partners forming the new Biograph company, Dickson created the 66 millimetre nitrate print. This was vastly superior and was taken up by other movie makers from London for next few decades.

William and Antonia Dickson later wrote an important book about the history of film from their points of view.

The role of London in further cinema innovation was largely dormant. Largely dormant but for one thing.

William Friese-Greene - the maker of the first featured movie - died in 1921. He’d been working on a new colour process, helped by his son Claude.

After 1921, Claude continued his father's work. Colour-sensitive black and white film was shot and projected through alternating red and green filters.

His movie ‘The Open Road’ was made all over the UK between 1924 and 1926.

After the rest of the filming for the ‘The Open Road’, Claude Friese-Greene returned to London to wrap up his colour movie.

Sometimes I finish a Substack post with an accompanying YouTube movie. This post is no exception but you get three for the price of one here.

Both the above 1891 movie and the below 1926 movie, mark the beginning and end of the initial phases of London innovation. The first black-and-white movie made in the capital and the first colour movie made in the capital.

In the 1926 one, you can see a variety of scenes and early motor traffic. A trip past mourners at the Cenotaph is particularly moving in my opinion.

Right at the bottom of this article is a YouTube video dovetailed by the 1891 and 1926 movies, plus illustrations of other films between the two dates made in London. Don’t say that I don’t spoil you!

A very interesting visit to the past, and s joy to watch, the collection of stories and film worthy of a paid subscription, I presume it is covered by copyright, to watch again would be a bonus if possible.

Thankyou.

Thomas.