Limehouse – London’s first Chinatown

An East End community, briefly famous

Around 1980, UK pop musicians stopped using Chinese-style riffs. I think the seminal hit that year Turning Japanese by The Vapors was perhaps the final example. There was a lack of a u in their band name but they were actually bad spellers from Guildford. There’s no racism in the song - just ignorance, playing a Chinese cliché guitar riff in a song about the Japanese.

China Girl by Bowie and Hong Kong Garden by Siouxsie around the same time also use Chinese melodic scales within. The ‘Hong Kong Garden’ was a real takeaway in Chislehurst by the way.

I can’t think of later examples - I think it stopped in pop music around 1980. Inter-community relations improved in Britain in the eighties - less ‘us and them’. Sitcoms such as Love Thy Neighbour and Mind Your Language disappeared from our TVs.

But there are certainly earlier examples. Around the time of the Second World War, we have my grandad’s favourite singer with his hit Mr Wu’s A Window Cleaner Now. George Formby’s lyrics grate somewhat to modern sensibilities but in summary, Mr Wu has been running a Chinese laundry in Limehouse but decides to became a window cleaner and his wife’s not happy. Did Our George know about pentatonic Chinese melodic scales as he employed them? Who knows?

I was trying to figure out what seemed ‘off’ in the lyrics. It’s certainly condescending in a Peter Sellers Goodness Gracious Me way but I think it’s the treatment of Mr Wu as the ‘other’ - exotic, mysterious, ‘inscrutable’ and living a very different way of life over there in Limehouse to George Formby.

The Chinese community of Limehouse was neither a long-lasting one nor huge in numbers but it has endured in London mythology.

Male Chinese sailors - known as ‘lascars’ to white Londoners - arrived on trade clippers following the Opium Wars. Opium gave Britain something to sell to China in exchange for tea. The sailors settled in two streets near Westferry station.

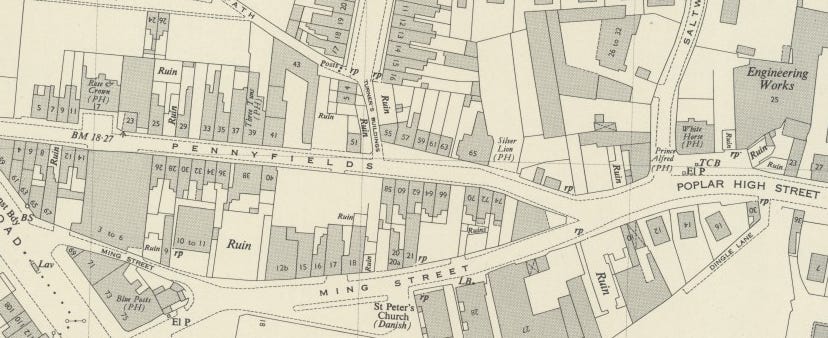

Chinese street names appeared and by 1890 two distinct yet small Chinese communities had developed: Shanghai migrants had settled around Pennyfields, Amoy Place and Ming Street in Poplar, whilst those from Canton and southern China concentrated around Gill Street and Limehouse Causeway.

Settling from the mid Victorian period onwards, the 1881 Census recorded only 109 Chinese migrants in London, most living in Limehouse. By 1891 the London total had risen to 302. Subsequently, Limehouse’s Chinese migrant population gradually increased, reaching 337 by 1921. Around 40 per cent of Chinese people counted in London’s pre-1914 censuses lived in and around only a handful of Limehouse streets.

Whilst Limehouse remained relatively small before the First World War, its highly distinctive ancestral heritage secured the area’s enduring place in the public imagination.

Charles Dickens, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and many social commentators wrote about this ‘exotic’ corner within the squalor of the East End, where drugs, gambling and unusual sexual occurrences allegedly took place. Dickens’s The Mystery of Edwin Drood starts in a Limehouse opium den and, 50 years later, Sax Rohmer’s tales of the evil Dr Fu Manchu continued to fuel readers’ interest about this supposedly exciting area so close to home.

Intermarriages between Chinese men and local women received disproportionate press coverage, as did several high-profile crimes in this relatively law-abiding Chinese community.

Amongst such sensationalist newspaper reporting was the case of London-born actress Billie Carlton, who had a starring role on stage at the huge Victory Ball held at the Albert Hall on 28 November 1918 but was found dead in her rooms at the Savoy Hotel shortly afterwards. She was a heavy cocaine and opium user who had been supplied with these drugs by an intermediary from a Scottish woman called Ada and her Chinese husband Lau Ping Yu, both living on Limehouse Causeway.

Such frequently exaggerated reports of illicit drug trading and gambling gave rise to a powerful set of ‘Chinatown’ myths about Limehouse that featured in other novels, films and songs. Thomas Burke’s collection of stories about London’s Chinatown, Limehouse Nights (1916), owed much, according to John Seed, to Jack London: ‘tough boozy narrators revealing the sordid and dangerous spaces of the East End to a nervous suburban readership’.

The criminalisation of opium and cocaine possession in the wake of the First World War continued to focus the minds of jobbing hacks on the possibilities of Limehouse, which was presented to the interwar popular reading public as a drug-addled ‘Orient’ in London’s East End.

In the 1930s, the Chinese community was at its peak of around 4000. Visitors seeking out the flesh-creeping places they had read about were disappointed to find streets of typical British two- and three-storey terraces with the odd sign in Chinese characters to make it different. Thomas Cook organised tours which staged hatchet fights between pigtailed actors bursting from doorways satisfied sensation seekers.

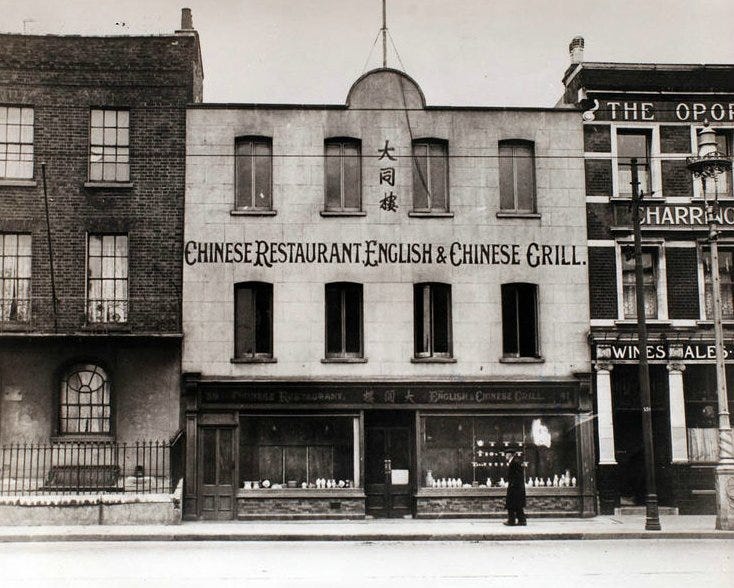

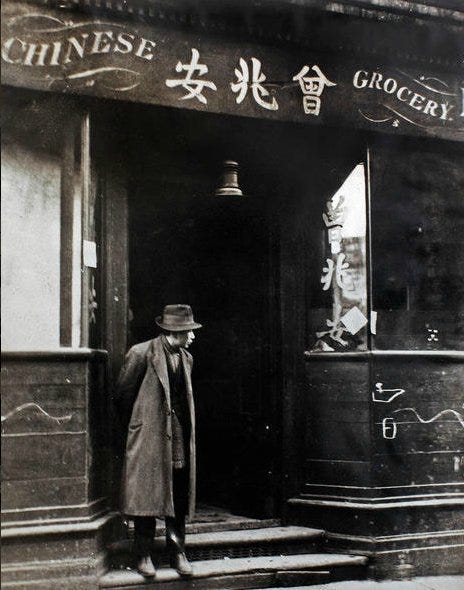

Actually, the Chinatown of Limehouse was only really identifiable by a few distinctive shops. There was the iconic architecture of Foon’s emporium at 57 Pennyfields, Chong Chu’s restaurant in Limehouse Causeway and the Chinese laundry on the corner of Castor Street.

Grenada House, started in 1937, was part of the first slum clearance programme in the area, obliterating some of the narrow street of shops and ‘opium dens’ so written about.

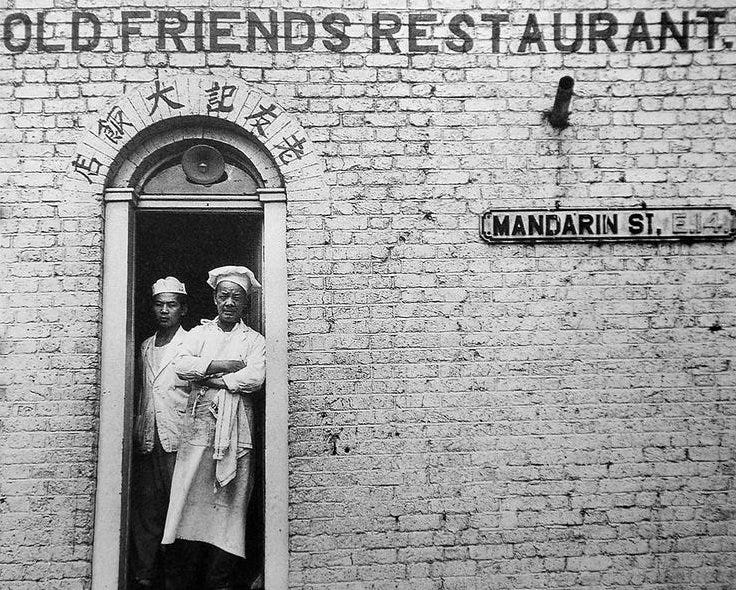

The area of Mandarin Street and nearby Pennyfields, was affected by slum clearance projects in the mid-20th century. Second World War bombing flattened further large areas. Instead of moving into the post-war blocks, the community relocated to London’s current Chinatown in the West End.

Take a modern trip to Ming Street and Limehouse Causeway and the area today is unrecognisable as a former ‘Chinatown’. There are no Chinese shops, simply post-war housing. The towers of Canary Wharf and its tall friends loom over the area.

NOTES

All images: Granger (NYC) Archive

Mr Wu himself originated in a 1913 stage play. He was a Chinese patriarch who tried to exact revenge on the Englishman who seduced his daughter. Gawd knows how he ended up as a window cleaner.

Love this one, the old stomping ground. We took Patrick Moore to a Chinese on Mile End Road, just up from our Physics building. I looked on the map and I don’t think it’s there anymore, a lot of stuff was cleared to make way for Mile End Park. Have mixed memories about my commutes down Burdett Road and Westferry Road 🤣

In the music category, I would add Dragon Town by Big Audio Dynamite (from Megatop Phoenix, 1989), which opens with a sample from Mr. Wu. Mostly about the joys of Chinese food on Gerrard Street, Soho.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kOE_sddtpIM