There’s a man whose life over one hundred years ago has been following me around a bit.

During the early to mid 1990s I was feeling a bit directionless in my career. A friend and I took a trip to a reasonably remote Scottish island and attended the 1994 Fèis Bharraigh, an annual Gaelic arts and culture event, held on Barra.

My friend knew a photographer based in the Isle of Lewis - five islands up the Hebridean chain of islands and by chance we ran into him in Castlebay that July.

Back home, I had been dabbling with the nascent internet and had ended up selling virtual real estate to people who wanted to live a parallel ‘second life’. New internet neighbours from around the world came to live in a made up street in a made up city that I had invented. I really had no idea what I was doing and didn’t know why random Americans would want to part with $5 to live next door in a pretend city to another person from Kuala Lumpur who paid the equivalent $5 in Malaysian Ringgit.

Sam the photographer had just started a film company on Lewis and had heard of the world wide web but didn’t know a lot about it. As I said, it was 1994.

We bonded over many pints that weekend. I told him of Antaro - my weird project - and he invited me to join his new company as a sort of ‘internet expert’. I ditched my previous life and later that summer, started to live on Lewis.

I think that I had imagined that my new life would be a bit Whisky Galore but the 20th century had reached the Western Isles too. So while the ‘everybody knows everybody else’ community was certainly a thing in the Outer Hebrides, there were also teleworking initiatives all around the islands, I taught computing classes to the elderly, Highlands & Islands Enterprise were starting campaigns for equality of broadband with the mainland.

I began work on a new website called the Virtual Hebrides and I was creating lots and lots of articles with the help of interviews, Stornoway library, locals down the pub etc.

I overreached myself by inventing flags for each of the six main Hebridean islands and two actually caught on, on their islands and started to be used. But mainly I did stay on-topic - I wrote about gathering the peats, Harris Tweed, whale strandings, Pygmies’ Isle. You name it. I wrote about it. One of the things I wrote about was the very interesting story of the settlement of Leverburgh in South Harris.

You’ll have noticed that there’s not a lot of London in this post so far. And you might be further surprised how I might shoehorn Hampstead Heath into this post. Hold on. I’m about to return to the man whose life one hundred years ago has been following me around a bit.

His story is a long one but a fascinating one which will take us from Lancashire to Leverburgh to London.

* * *

William Lever was born on 19 September 1851 at 16 Wood Street in Bolton. He was the eldest son but the seventh child of James Lever, a grocer, and Eliza Hesketh, whose father managed a cotton mill.

In 1879, the Levers bought a struggling wholesale grocer in Wigan, giving young William the chance to demonstrate his abilities. This expansion required finding new suppliers, which took William to Ireland, France and across Europe. His talent for advertising and branding emerged as he effectively distinguished Lever products from the competition.

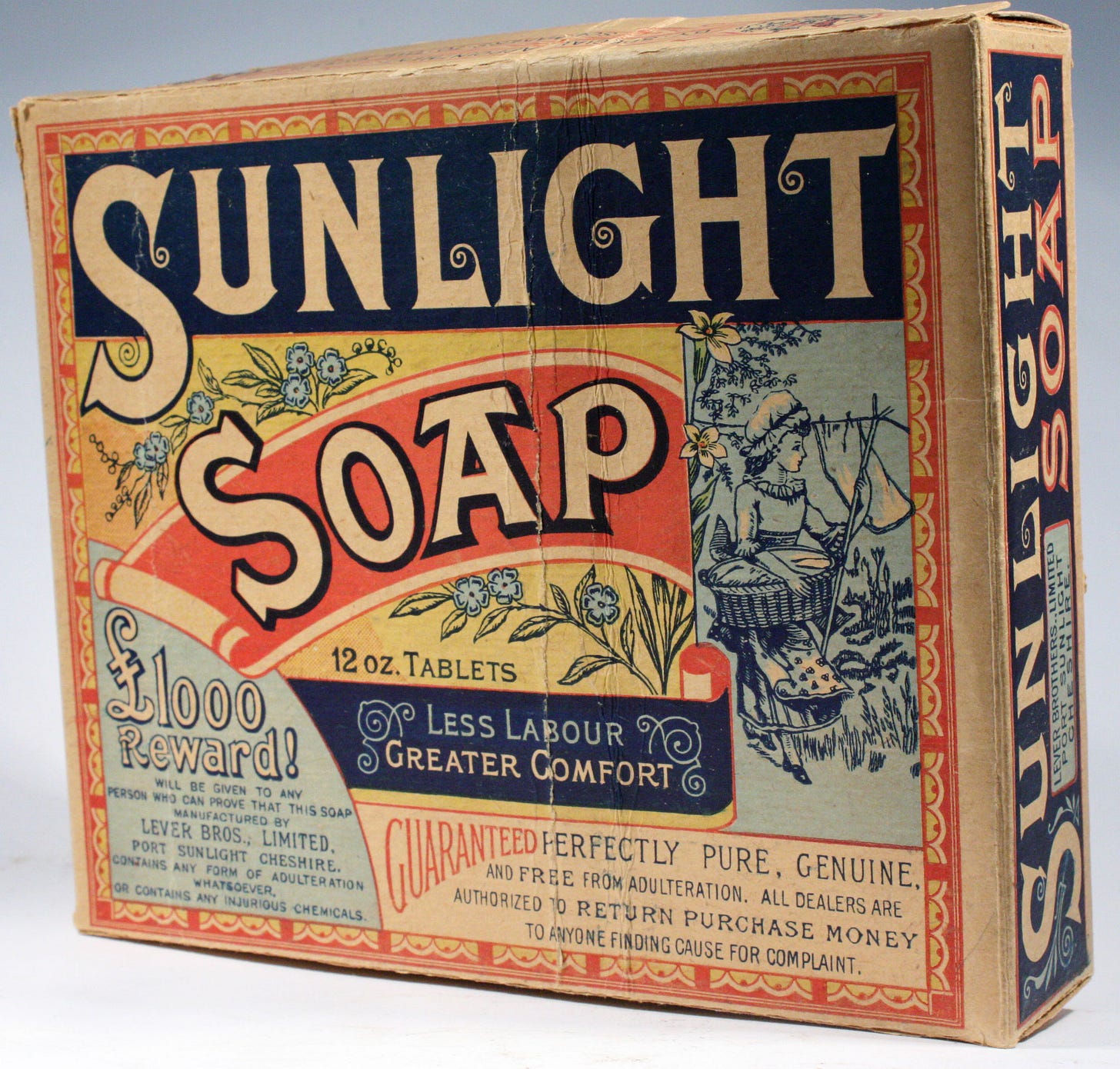

In 1884, William set out to gain a significant portion of the international soap market. Rather than selling soap by weight, he cut it into small, manageable tablets which were individually wrapped. Lever registered several trademarks, including ‘Sunlight’, which later became a house style applied to various household soaps.

The Sunlight brand's success was remarkable. By late 1887, it became impossible to extract any more capacity from their Warrington plant. Lever decided to relocate the entire manufacturing operation to an 11-acre green-field site near Birkenhead.

In 1887, Lever acquired 56 acres of land and this location became Port Sunlight, where he constructed his factory and a model village for his employees. From 1888, Port Sunlight offered decent living conditions based on the belief that good housing would ensure a healthy and contented workforce. The community was designed to house and support workers. In practice, workers' social lives were monitored from head office, and some employees clearly resented his paternalism.

In May 1918, the now Baron Leverhulme purchased the Isle of Lewis for £167,000 and in late 1919 acquired the South Harris estate for £36,000. His vision for their prosperity centred on applying modern science and business acumen to establish a thriving fishing industry.

Leverhulme planned to enhance and expand the port of Stornoway to attract fish landings from visiting vessels, supplementing catches from local boats and his modern fleet. He envisioned an ice-making factory and refrigerated cargo vessels to transport fresh fish to his Fleetwood depot in Lancashire. He expanded herring-curing capacity and fish processing facilities, installing a canning factory and a plant producing fishcakes, fishpaste, glue, animal feed and fertiliser.

Leverhulme acquired fishmonger shops across Britain's larger towns and cities, modernising them and retaining previous owners as managers. This concept was named MacFisheries - some of us old ‘uns might remember that name from our high streets. (He acquired other food enterprises including the Wall's ice-cream and sausage manufacturer).

Leverhulme strived to win Lewis islanders' favour and popularise his schemes but the unfair Scottish land ownership laws of the time were a parallel theme.

In summer 1918, the Scottish Office proposed that under the Small Landholders (Scotland) Act, the Agriculture Board should acquire certain Leverhulme farms on Lewis to create nearly 150 crofts. Leverhulme opposed this. He believed he could improve living standards until crofting became obsolete and grew impatient with political processes persisting with "futile land reform" rather than allowing him to act as the Western Isles' effective 'monarch'.

In 1919, locals began seizing Leverhulme's Lewis farms, driving off livestock, demolishing boundary walls and marking six-acre plots. By summer, sixteen of twenty-two island farms were affected.

Returning from a US business trip in early 1920, Leverhulme discovered continued raids. He adjusted his plans.

With local permission, he renamed the fishing village An t-Òb as Leverburgh and proposed concentrating his efforts on South Harris. Left with unwanted island land in Lewis, Leverhulme sold what he could, though many buyers primarily sought shooting and fishing rights. After his 1925 death, Lever Brothers quickly halted all Harris development, ending Leverhulme's Western Isles scheme with minimal achievement.

By 1930, Lever Brothers employed 250 000 people and had become Britain's largest company by market value. That same year, the firm merged with Dutch company Margarine Unie to create Unilever. Unilever might be regarded as the world’s first truly multinational corporation.

* * *

At some point during the mid 1990s I wrote up this story for the Virtual Hebrides. My life then took another turn. And then, career-wise, further turns.

I began my story here in 1994 and I’ll fast forward to 2022. I’d started a project to walk between every tube station, seeing what was en route.

One of these walks took me past our former house in Golders Green. The walk became a meandering affair taking in the Hampstead Heath Extension, Wylde’s Farm and North End. Stopping for a pint at the Bull and Bush, I then crossed the main road and started to explore the west part of the heath. I was then stunned to came across Inverforth House. I had lived a year in Golders Green and never experienced, in all that time, this pergola-filled extravaganza.

The house was built in the British Queen Anne Revival style in 1895 and - according to a passing visitor who I met that day - who should then move in but good old Lord Leverhulme?

Virtual Hebrides-like, I did some research after this chance encounter with this wonderful place.

Lever had acquired The Hill in 1904 - only after his death was it renamed Inverforth House. He reconstructed the property, adding wings on each side plus a ballroom and art gallery.

He engaged Thomas Mawson, a landscape architect and garden designer, to fulfil his vision for the grounds. Both Lancashire natives, Lever had previously employed Mawson for various projects throughout the country.

Mawson’s principal challenge involved elevating the gardens by 20 - 30 feet to establish a terraced landscape. These terraces were formed using excavated material from the Northern Line's extension to Golders Green which was being built at exactly the same time.

In 1911 and 1914, Lever purchased two adjacent properties to enlarge his garden. Fond of land disputes, this sparked a disagreement with Hampstead Borough Council regarding Lever's desire to incorporate a public right of way to connect the two plots, a matter that remained unresolved to his satisfaction. From 1919 until his death in 1925, The Hill served as Lever’s principal residence. In 1925, it was renamed Inverforth House.

Inverforth House was converted into two houses and seven flats in the late 1990s but the gardens are now run by the Corporation of London, meaning that the public can freely access this ‘secret’ garden.

The Hill Garden and Pergola truly evokes the sensation of discovering a forgotten civilisation.

There are elevated stone walkways flanked by pillars. Ivy and flowering plants climb around them and overhead. Below the walkway stretch beautiful landscaped gardens and beyond them the heath.

In summary: it’s lovely.

NOTES

Yes - there’s a video. See below…

I missed last week’s article. Alas, my partner was diagnosed as terminally ill and other matters became much more important. I will try to set aside time each week to write these Substack posts as the distraction is probably quite good for me. I realise that this distraction caused this week’s article to have a bit of navel gazing within it. I hope you don’t mind and please bear with me if I miss another post deadline in the weeks to come. I’ll try not too.

Glad to be reminded of Iverforth House - a lovely spot. And I like your project to walk between every tube station. Sorry to hear about your partner - I wish you both all the best.

I was very saddened to read that footnote - my best wishes to you both. I can also remember discovering the Pergola and Hill Garden for the first time, around the turn of the century, and not quite believing it was real. It’s a lot better known these days, thanks to Insta and TikTok, which is good to see, but also robs the place of some of its magic.