For the last fifteen years, I have been obsessed with the histories of the streets of London.

I started to write them down in the hope, some day, of publishing a book or two. But I didn't get around to the book, partly because there were always so many gaps in the streetscape of London I couldn't yet fill. Who built Acacia Avenue, N17 and when? Which king was King Street, Hammersmith named for? Until I knew many more local facts, it would make for a patchy sort of a book.

Around 2011, I noticed to my surprise that the website domain "The Underground Map" (theundergroundmap.com) was free to buy for just over a fiver. So I bought it. A little time after I had started the website, I started a Facebook page of the same name.

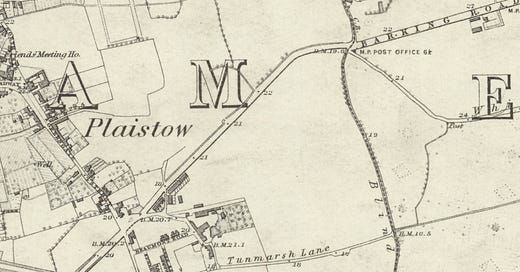

I've always been fascinated with old maps as well. I love their beauty simply as pieces of art - but also what they show; what they don't show; how the landscape of London changes over the decades, from farmland and green fields, to densely populated suburbs.

Old maps of London and street histories are both central to the website I went on to develop.

I sourced a whole bunch of nineteenth-century maps to use. And luckily, Crown Copyright on Ordnance Survey maps expires after 50 years so they are free to use just as long as - at time of writing - they predate Mud singing "Tiger Feet" on Top Of The Pops.

I had always wanted to see the various areas I knew in previous years - how they developed; how names changed over time. I organised the mapping on the website into decades so the changes could be witnessed.

I found out that the house I spent the first six months of my life in was not only demolished, but, where it stood was unexpectedly turned into a park. A century earlier, before it was the site for our house, people kept pigs there.

I recognised from the comments on the website, and on the various associated social media accounts, that other people also wanted to see the place where they grew up as it was in earlier days. And where their parents and grandparents grew up too.

Now the old maps were online, I could start to attend to the streets. A current list of all streets could be gleaned from OpenStreetMap. Online can be found old street directories, census returns, old pubs, street name changes and more.

But, best of all, I was in an Oxfam shop in 2019 and somebody had decided to part with their "London County Council Names of Streets and Places In the Administrative County of London" (1912 edition). This was a goldmine.

I now know that there are somewhat over 90,000 streets, past and present, within the current area of the M25. Over 5000 of those streets no longer exist - many were swept away when new estates were built post-war. Many still exist but were renamed.

Progress though was proceeding at a stately pace.

My working life had been largely spent in the aerospace industry. With family and household duties, I worked on The Underground Map project very sparingly in my spare time. After an intense day at the office, working on London history provided a complete change of scene to relax with for an hour or so, just to clear my mind. But it was only five hours a week.

As Covid hit, my main work activity was organising a major annual space conference. That stopped completely and I had a lot of time on my hands. I started working eight hours a day on The Underground Map and, when society started to resume normality, I found that I enjoyed my hobby much much more than organising conferences.

So since 2020, I've done the project full-time. Financially a bit foolish maybe, but much more rewarding than making sure that catering is reliable in Exhibition Hall B.

I have spent a lot of time in the past four years trying to locate each of the disappeared streets of London on the old maps. I have about 2000 of these left to do, so I'm getting there. It’s become natural to Google my way to finding street locations and the search results - often care of the outstanding British History Online - not only help me locate old streets but tell me about their build dates, name changes and more.

The Underground Map website now has the aim of (geo)locating every street, existing or long gone, on the old maps so that somebody can find their street - if they want to find it. And as I find street histories, these are added at the same time.

Things I’ve learnt along the way

Many road namings were political, and then suddenly they weren’t: Royal names at first - countless Queen Streets, George Streets and Charles Streets. Then mid-nineteenth century, aristocrats and Prime Ministers started to be honoured, especially if a battle was involved - Blenheims, Marlboroughs, Wellingtons and Palmerstons can be found throughout the inner suburbs. In the twentieth century, that ‘kowtowing’ naming behaviour largely stopped - Asquith Street, Thatcher Drive or Blair Road are few and far between.

Squiggly borough boundaries can have an underlying reason: The current boundary between Westminster and Kensington & Chelsea is a ridiculously bendy affair when seen up close, and seems completely random on a modern map. On a map dating from the turn of the nineteenth century, the River Westbourne ran above ground and formed the border. It still does form the boundary, but now it's a buried river. Want to know where the river flowed? Simply cross into the adjacent borough and it was there at the signpost welcoming you to Westminster. Similarly, the location of Dexys Midnight Runners Come On Eileen video is Brook Drive, SE11. ‘Brook’ Drive since it once flowed along the banks of the culverted River Neckinger, and the road separates Lambeth and Southwark causing no end of bin day confusion.

If you were a teenager as the First World War ended, before you were forty you’d have seen the geographical extent of London's urban area grow faster than at any point before or since: One particular amazing thing is the growth of the built-up area of London during the interwar years. In 1918, the countryside in northwest London began at Kensal Rise. By 1938 - just twenty years later - the contiguous building had reached beyond Edgware. That's a distance of seven miles, all covered in housing in every compass direction, built within two decades.

London ran out of road names and so they’ve become sillier over time: Not only all those new interwar roads but two Post Office initiatives (1880s and 1930s) to rid the capital of duplicate street names. We now suffer from much faux-rural nonsense - The Pantiles, Meadow Barn, Cuckoo Glade - all over outer London. GLC out-of-town estates had whole road naming themes so that they didn’t run out - nearly every 1950s-built street in Borehamwood commemorates a town or village on the A1.

At last, a book!

Of sorts. Right at the top of the article, I mused over my lack of progress in creating a publication from all this effort.

Well, that’s now a thing of the past. I seem to have finished a whole area of London. Thanks to a particularly well-documented history of a particular place, I present:

Every street in Hampstead Garden Suburb (download link)

Street histories at the top of the document; old maps at the end of the document.

Hampstead Garden Suburb is extremely well-covered on the web which is why it’s the first one I’ve completed. But it’s rather uniform - this architect designed this road, that architect designed that road. Once we get to, say, Soho, it’ll be a veritable history fest.

This won’t be the last but it is the first of the upcoming PDFs. For reasons of my own, I split London into 998 named areas. I’m being ambitious but that’s 997 more of these collections of street histories and old maps to come, bundled into PDFs, and in time covering your area.

Being PDFs, I can update with new facts, fix typos and errata as I find them and then regenerate. There’s an upside to not publishing a physical book.

Even if you are not familiar with Hampstead Garden Suburb, you’ll get the idea. I’ll publish new areas regularly.