By the time of the Victorian era in the UK, there were thousands of thoroughfares called High Street or London Road. These caused no issues, as each town would have only one ‘High Street’ and only a single ‘London Road’ - the road which led from your town in the direction of the capital.

But the population was increasing and especially after the railways afforded the creation of brand new suburbs, many streets were being created which all needed a name.

Earlier in the 19th century, many landowners who were laying out new areas kowtowed to the Royal Family - especially the Hanoverians. There were King Streets, Queen Streets, George Streets, Charlotte Streets all over the country. Once Empire was truly under way, battles and British victors of those battles were a thing: witness all the Marlborough, Wellington street names.

Duplication of all sorts of names meant that navigation within larger towns was becoming difficult. City maps were slow to develop and the skills to read those maps were even slower to catch on.

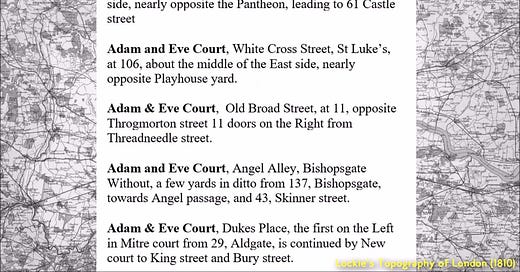

In London for instance, at the beginning of the 19th century the only ways of describing London were convoluted descriptions of how to get to each street.

This is simply an example. There were many more than five Adam & Eve Courts in the capital. There were so many duplicate street names that London was a bit of a mess to navigate.

My own father kept up this tradition well into the 20th century. Needing directions on how to get to a particular place, he'd supply directions from pub to pub, using which pub was on a corner and looking down the street to the next one.

The introduction of a UK-wide postal service in 1840 spurred the Victorians into action.

The work of many postal workers was made quite difficult. Many letters went to the wrong 14 King Street which was in close vicinity to the correct 14 King Street. The person posting the letter needed to be specific as to which one they meant.

The powers that be saw the thousands of duplicate street names in London and this confusion started to be addressed.

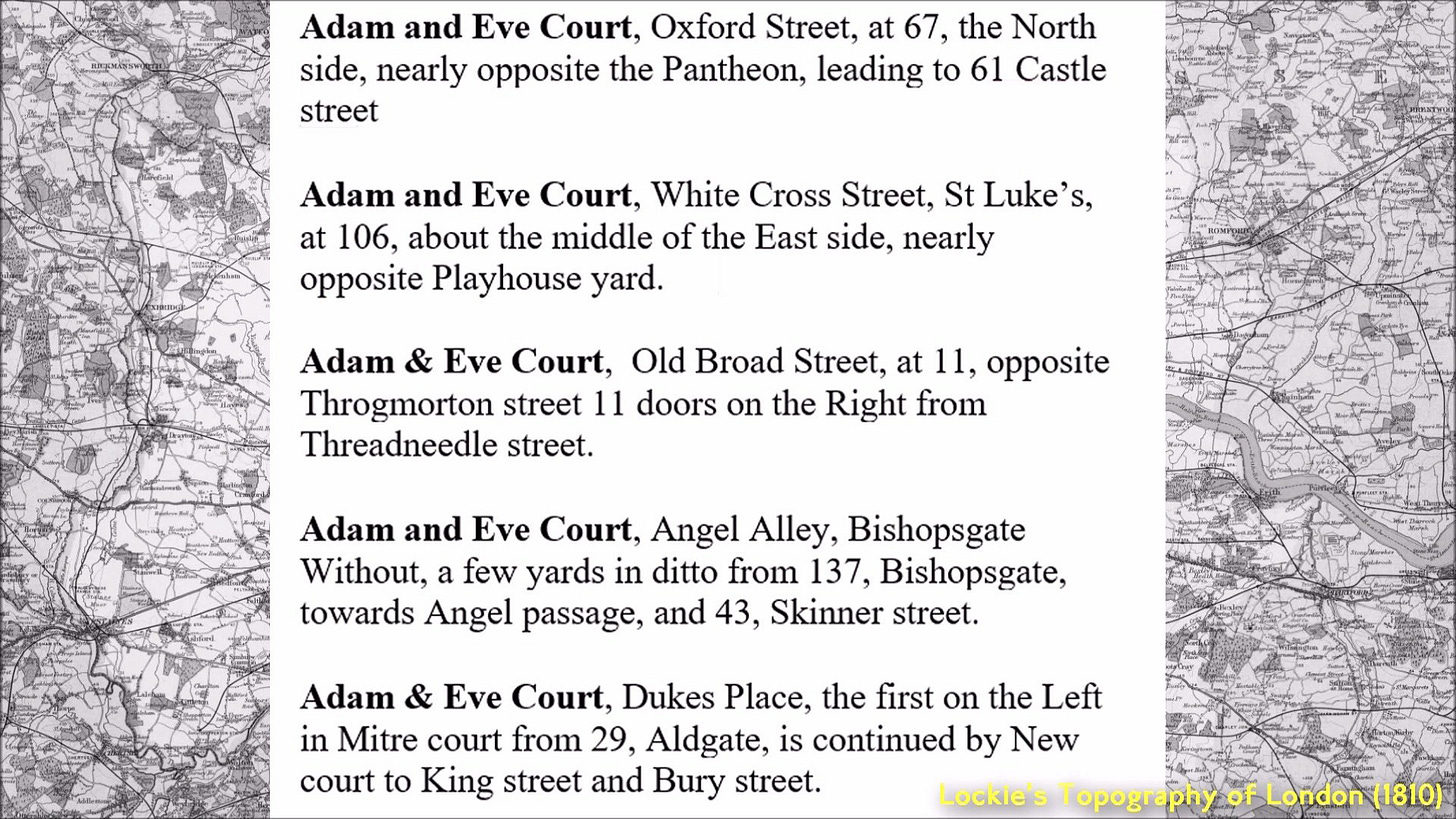

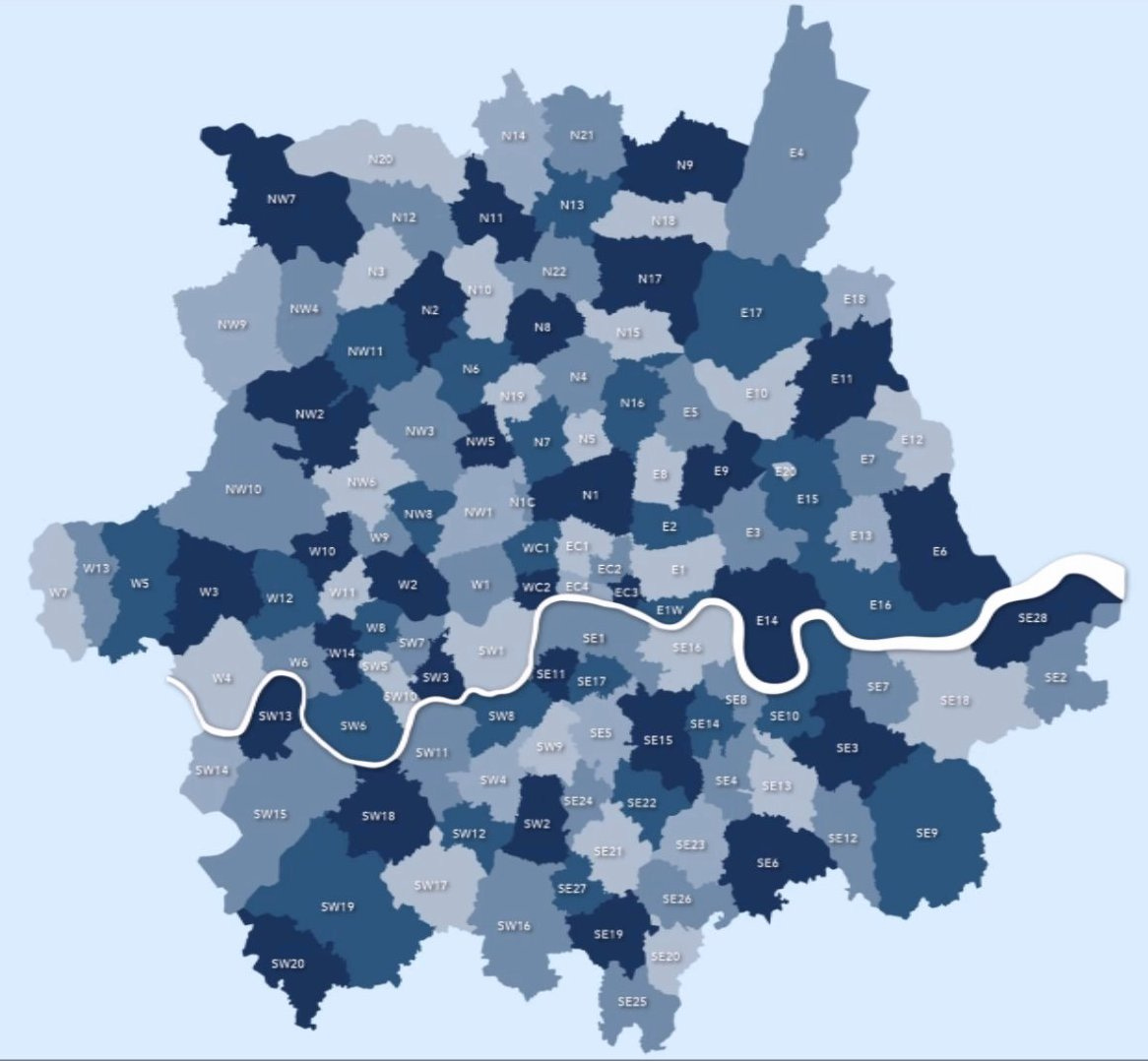

In 1857 London was divided into 10 postal districts with the codes to be added to addresses written on envelopes:

EC (East Central), WC (West Central), North, Northeast, East, Southeast, South, Southwest, West and Northwest:

The South and Northeast sectors were later abolished but certain roads in London have kept the signs from this period. Malvern Road in Seven Sisters was located in the short-lived ’NE’ (North East) postal division of London. The NE division was split between the N and E districts, with this section being given to N17.

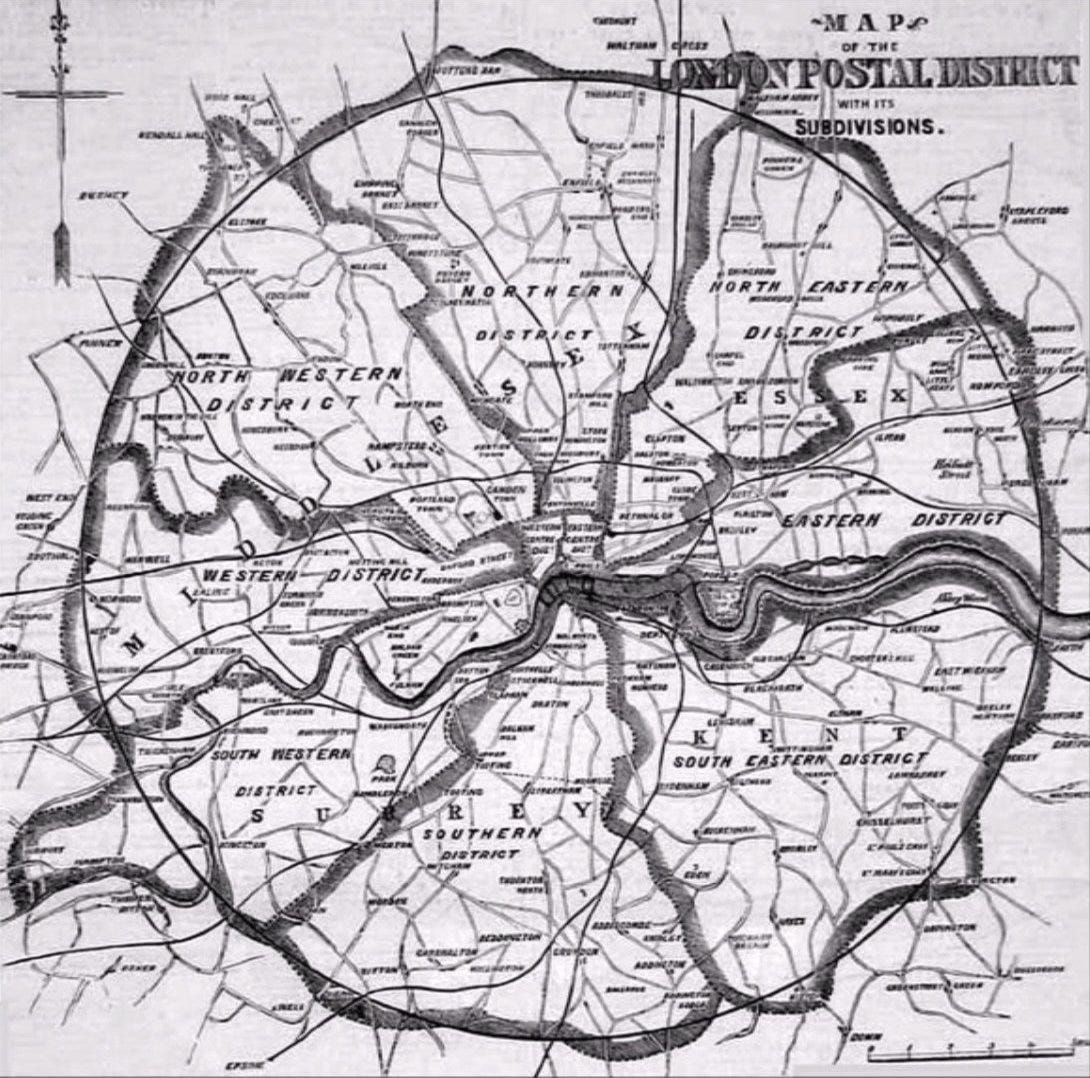

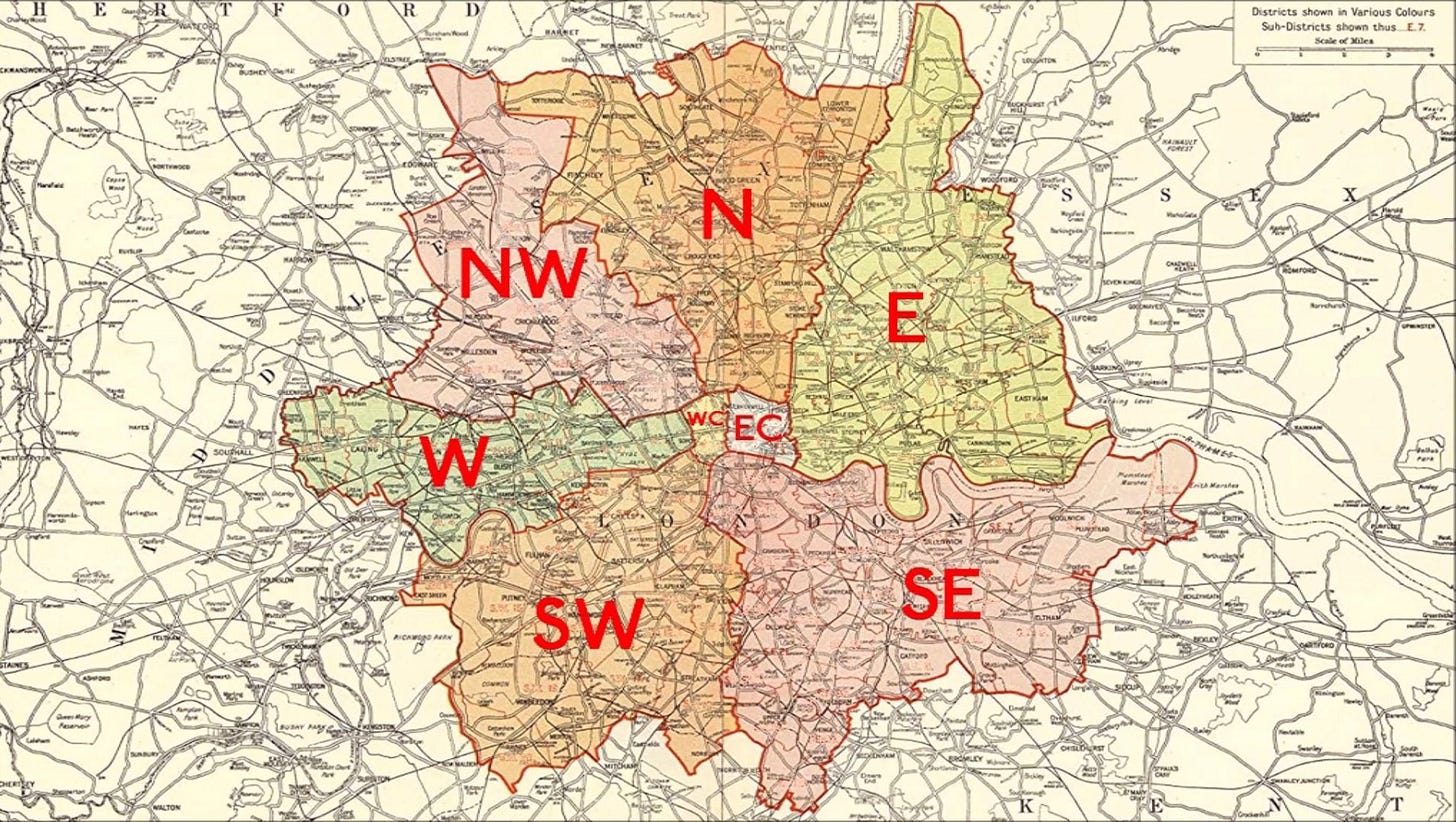

The late Victorian map looked like this:

During the 1880s and 1890s, our Victorian forebears began to remove duplicate names from each district. Too many Park Roads in the SW postal district? Well, we’ll keep one and rename the others. Thus, in Battersea there’s a Parkgate Road. In Wimbledon, there’s a Parkwood Road. In Collier’s Wood, there remains a Park Road. All three were originally Park Road. Other renamings were much more creative.

In 1917, as a wartime measure to further improve efficiency, each postal district was further subdivided into sub-districts, each identified by a number:

In the late 1930s, there was another batch of renamings to ensure that in each numbered postal district there were no duplicate names in London whatsoever.

Similar things happened to the road system.

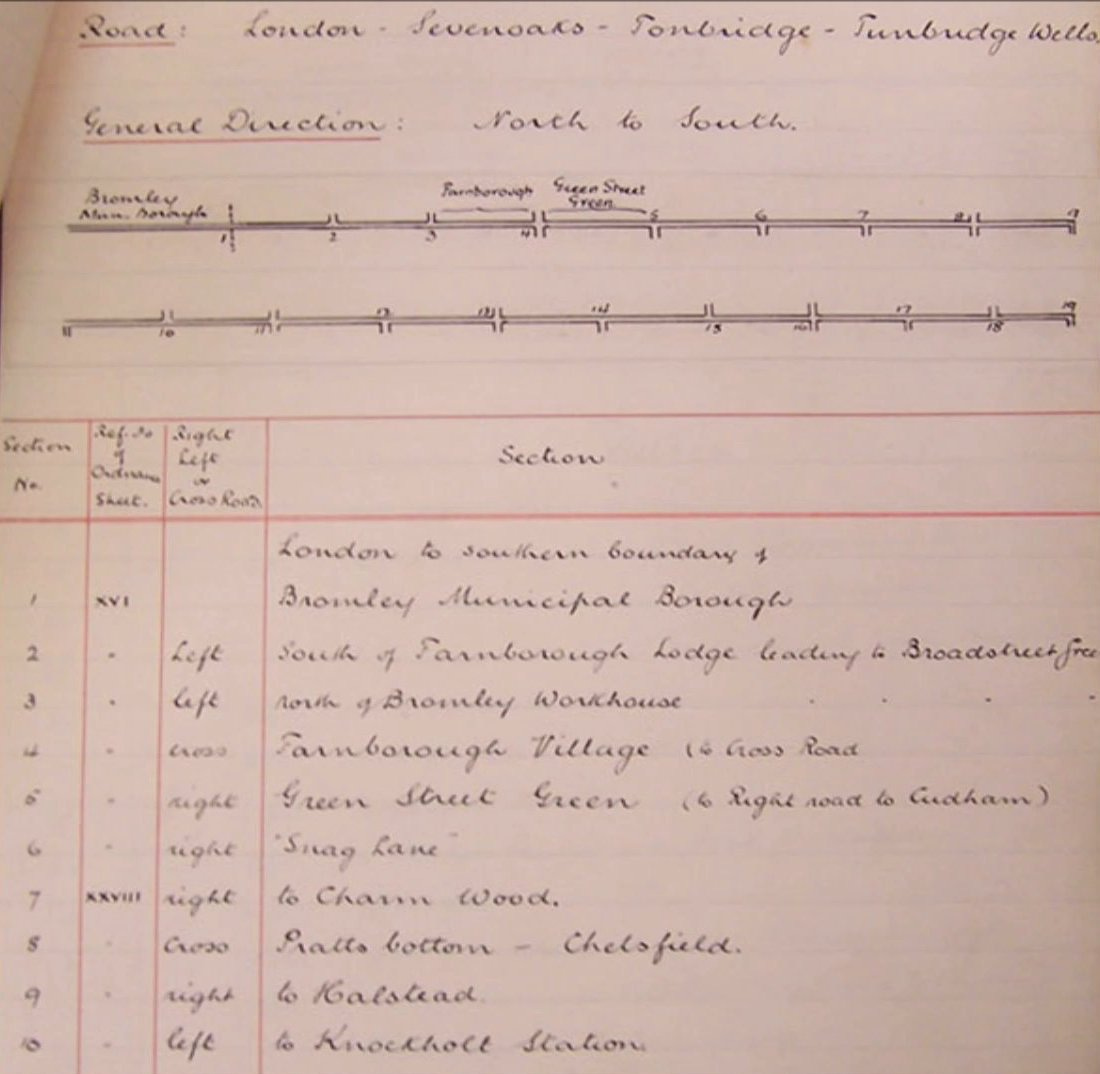

National navigation was quite difficult until just after the First World War.

Watling Street for instance led from London to Holyhead, but if a driver stopped for lunch in Oswestry, which way out of town led to Holyhead? Was it Willow Street? Shrewsbury Road?

Work on road classification began in 1913 by the government's Roads Board.

A classification system was created under which important routes connecting large population centres were designated as class 1, and roads of lesser importance as class 2.

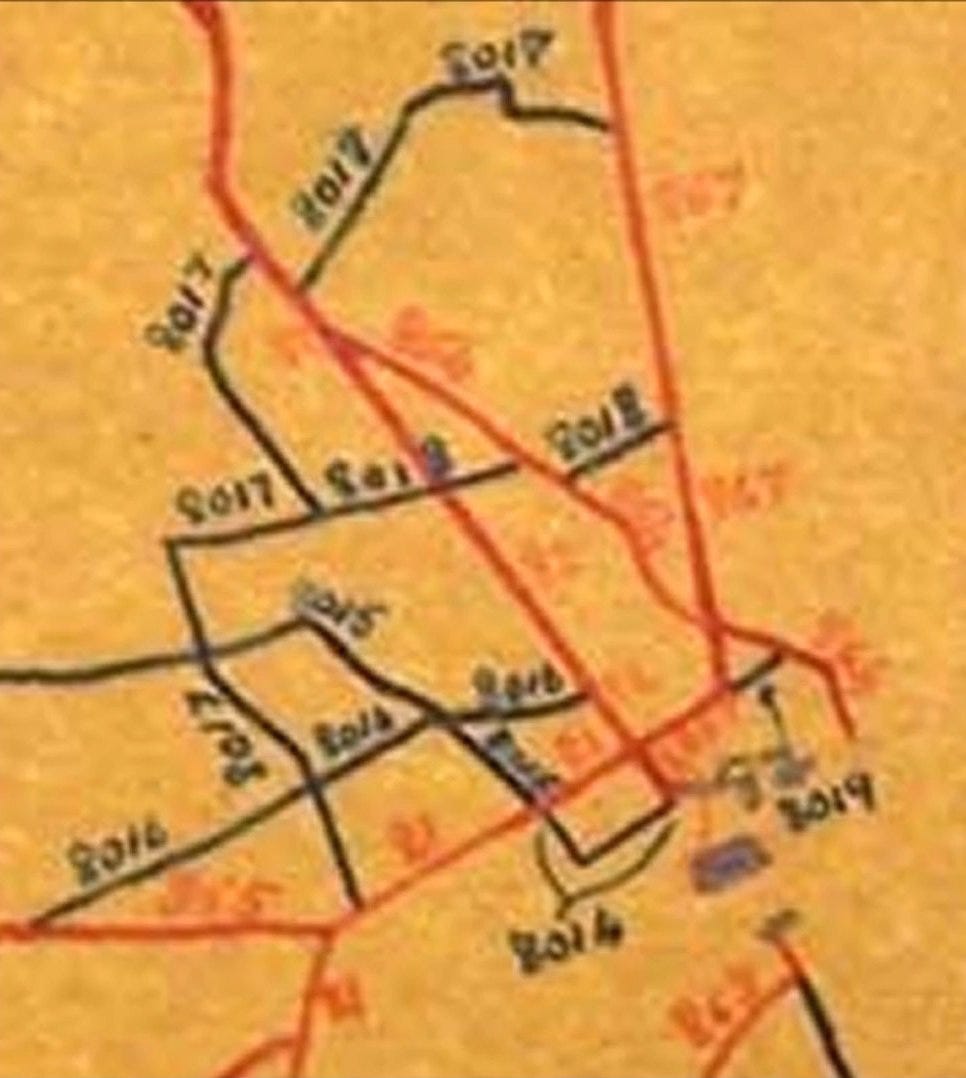

The definitive list of these roads was published on the 1 April 1923 and in time this evolved into the A roads and B roads.

Shortly after 1923 these numbers started to appear in road atlases, and on signs on the roads themselves, making them a useful tool for navigating motorists.

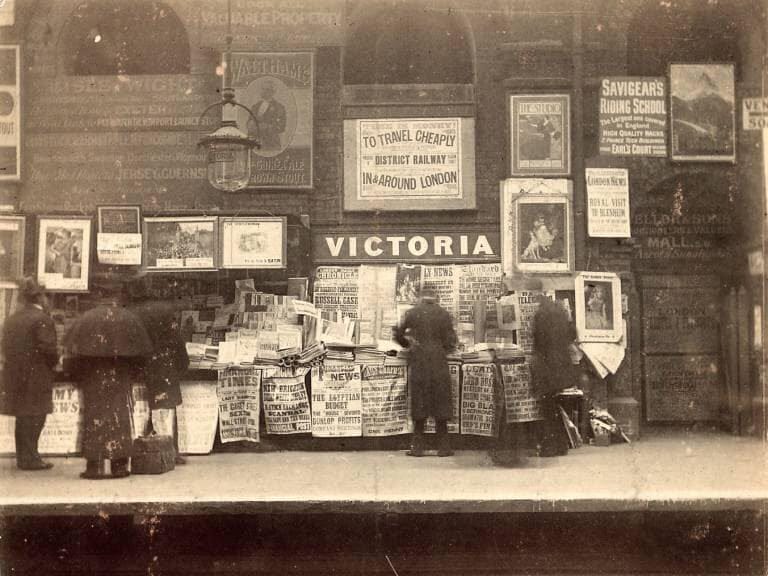

These changes - both giving roads a postcode and route number - were part of a trend for information which had been imparted by large swathes of text to be replaced by simpler visual and numerical systems. A similar story occurred with the telephone system.

The images above and below demonstrate this simplifying trend. The sheer amount of text alongside the entrance to the nineteenth century Victoria District line station would give me a headache these days. There is simply too much to take in.

Once inside Victoria station, the story was the same. This newsstand is surrounded by words.

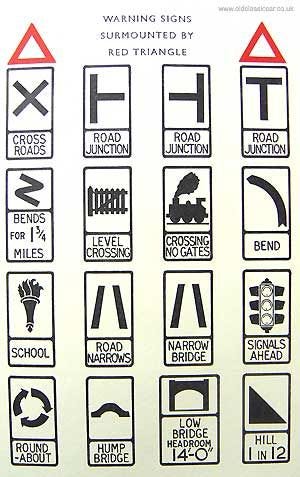

During the interwar period, road sign designers were beginning to reflect this change. The national system had simpler graphics but with text underneath to explain the graphic. (The symbol for School needed this explanation!)

As time went on, generic signs began to drop all of the words. People knew what they meant.

In summary, there has been a societal trend to simplify information. For roads in particular, to find smaller roads this has meant the adoption of postal codes. To navigate larger roads, this has meant the classification of A, B (and M) roads.

This trend extends to many facets of modern life: all-digit telephone numbers, internet codes and much much more

If I had more space, I’d go into my own opinions about how we now consume snippets of information rather than being patient with large amounts of text. And further with my own opinions about how this tendency has us relying on soundbites and not research, causing all of our modern political problems.

But Substack is reminding me that this post, with all the graphics, is “near email length limit”, so that’ll wait for another day.

NOTES:

Many images above from the excellent SABRE UK roads website

https://www.sabre-roads.org.uk/

At the beginning, there was a classifications of C roads too

Fascinating summary! Thank you, Scott.

There are many Hams but only one adjacent to Sandwich!