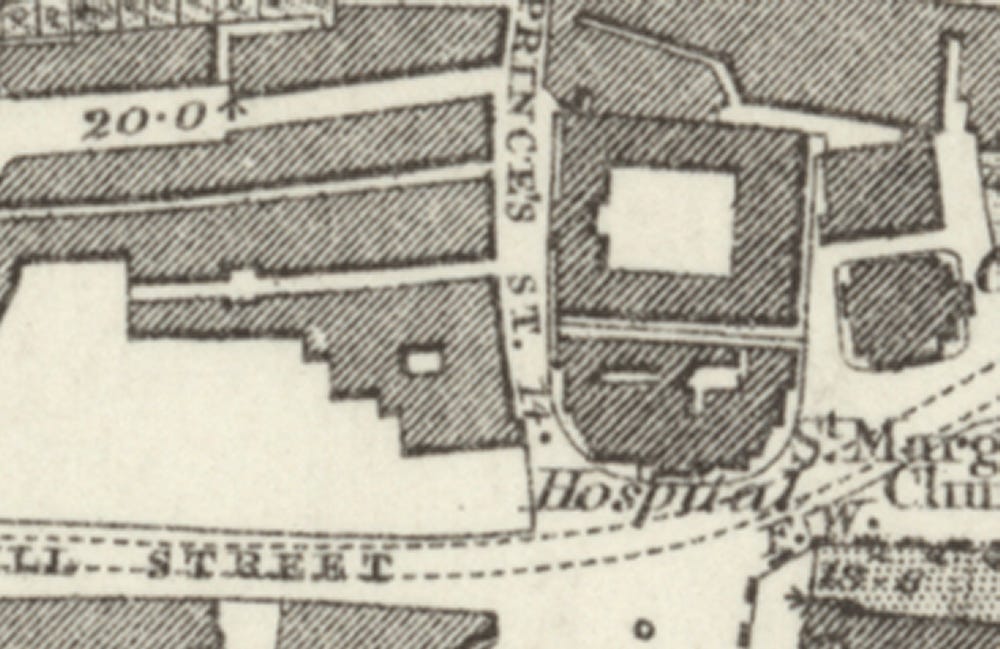

Property prices in Westminster are quite out of reach for us mortals. Taking the 1870 Ordnance Survey map below, it shows a maze of mostly poor streets. In the 2020s, most of the area west of the Thames isn’t ‘zoned’ as residential any more. Discounting all the landmarks (the Houses of Parliament, Westminster Abbey etc.), the area now contains offices, some government buildings, shops and pubs here and there.

Those lucky enough to have residences in this section of SW1 can include members of parliament in their second homes, members of the House of Lords and the odd aristocrat and millionaire.

No doubt on the east bank of the Thames, there are still relative bargains in the back streets of Lambeth but you’d still be lucky not to part with a huge wad of cash.

Back to the west bank and well into the twentieth century, things were rather different. Along with parliament, Westminster School and the Abbey, Westminster was a hive of industry amidst a lot of poverty - boat yards lined the river; noxious factories thronged the neighbourhood; there was a gas works (under the S of WESTMINSTER if you’re looking).

And, most disconcerting for our forebears, was the Pye Street Rookery - not so far from the centre of government.

But don’t take my word for it. Take the word of Thomas Beames who wrote ‘The Rookeries of London’ in 1852:

Among the worst districts in London, is the locality near Westminster Abbey, bounded on the north by Victoria Street, (which has displaced a host of obscure courts and alleys,) on the east by Dean's Yard, on the south by Peter Street, on the west by Stretton Grounds. Till the time of James I., this district was laid out in open fields, dotted at rare intervals with a few houses.

Sir Robert Pye, a courtier of the period of Charles I., had a fine house and garden near this spot, on the site of which, a few years afterwards, were erected Pye Street, Duck Lane, Stretton Grounds, and the adjacent alleys. Orchard Street, too, owes its origin to the same period, and is supposed to have been built upon the orchard belonging to this Baronet.

Of this now degraded locality, Strype, writing in 1720, says,- "Stretton Grounds is a good, handsome, long, well-built, and inhabited street which runneth up to Tothill Fields, almost against the new workhouse for employing Poor People; and hath on the West a passage into the New Artillery Ground, a pretty large enclosure, made use of by those that delight in military exercises. Pye Street lieth between Duck Lane and Great St. Anne's Lane, better built than inhabited. New Pye Street is a passage from Old Pye Street into Orchard Street, a pretty, handsome, new built place. Orchard Street very long, with good buildings, which are well inhabited. On the North side is a place called the New Way, which hath houses on the West side, the East being Sir Robert Pye's garden wall."

On the 27th of January, 1741, Lord Tyrconnel, in moving for leave to bring in a bill for the better paving and cleansing the streets within the city of Westminster, said,- "It is impossible, Sir, to come to this assembly, or to return from it, without observations on the present condition of the streets in Westminster, - observations forced on every man, however inattentive, or however engrossed by reflections of a different kind. The filth, Sir, of some parts of the town, and the inequalities and ruggedness of others, cannot but, in the eyes of foreigners, disgrace our nation, and incline them to imagine us not only a people without delicacy, but without government - a herd of barbarians - a colony of Hottentots." Such was the state of the roads, we are told that, when the King's state coach passed along at the opening of Parliament, the ruts were so large, that faggots were thrown in to fill them up.

It would seem that the materials for a Rookery were accumulating more than 130 years since ;-that, at a later period, Lord Tyrconnel was obliged to make the complaint detailed above;- that, from too common neglect, whilst improvements were made between the Abbey and the Bridge, the narrow courts and alleys which had grown up on the western side, were suffered to degenerate, till, in process of time, they became one of the worst resorts of thieves and prostitutes in the Metropolis.

You get the picture.

And the picture is even more clear with the help of this photo of Parker Street dated 1905.

Victorians, and after them Edwardians, became increasingly ashamed of the slum conditions at the heart of the British Empire. Parker Street, for instance, was some 250 yards from the Houses of Parliament.

Parker Street had been a row of Georgian terraces, but by the turn of the 20th century these had long been subdivided and turned into cheap lodgings.

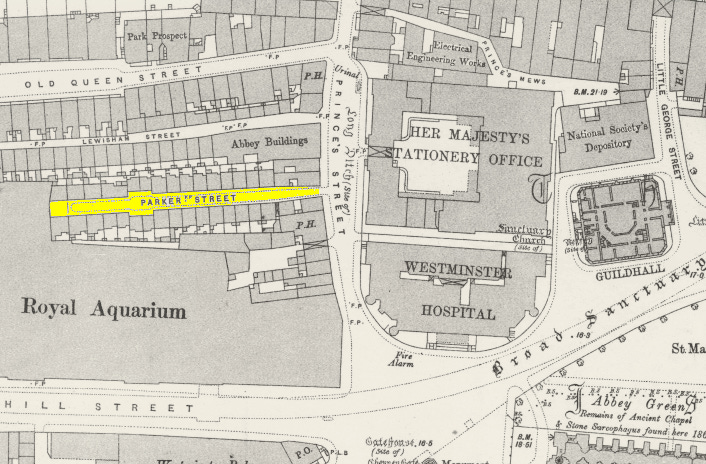

On the 1870 map, Parker Street was north of Tothill Street.

The big square shape off-centre is the modern site of the Queen Elizabeth II Centre (then the Stationery Office) and Parker Street led westward.

It’s better viewed on the 1895 era map behind the wonderfully named Royal Aquarium (a ‘place of amusement’ which opened in 1876 and was demolished in 1903. Methodist Central Hall now occupies the site).

Parker Street was notably close to Westminster Abbey - Abbey Green can be seen on the above map.

The London County Council cynically instructed the residents of Parker Street to leave their homes briefly and pose for a 1905 photo. This was because the LCC wanted a record of the street before the bulldozers moved in. The ‘slums of Westminster’ were finally done away and the L-shaped Matthew Parker Street replaced Parker Street. It’s a little different in atmosphere to its predecessor.

So now for a quick break from the poverty and we’re in the hands of the Victorian artist, Henry Pether. His view follows the River Thames from Millbank and looks towards the Palace of Westminster, which was completed in 1859, the same year he made this work.

That’s a fabulous moon. I can almost imagine myself into the painting. Henry Pether has arranged his foreshore boats in a picturesque manner. But it didn’t look like that. It looked like this:

Millbank was a zone of industry. A chimney rears its head in front of the Victoria Tower. Not far from that chimney sits the House of Lords.

Though Sir Joseph Bazalgette threaded his 1860s sewer through the scene connecting his Millbank section with the Victoria Embankment beyond parliament, he otherwise left things alone.

On the 1870 map, the area looks like this:

Even in 1895, the wharves, works and factories remained. Indeed it’s worth looking at the sheer variety of premises. I bet that oil factory was popular:

For me this land use, where it is, seems inconceivable. The Edwardians agreed, and while they were getting rid of the rookery, they decided the boatyards should go too and replaced it with the ‘Victoria Tower Gardens South’.

Further south along Millbank was the Millbank Penitentiary. I have discussed this prison before and I won’t repeat myself. But prisons are generally not placed in posh areas. On the 1870 map, for reasons of secrecy, its location was depicted as a big blank space:

By the 1850s, it was London's largest prison and housed convicts from all over the country. The prison closed in 1890 and was demolished shortly after. The much posher Tate Britain art gallery now stands on the site.

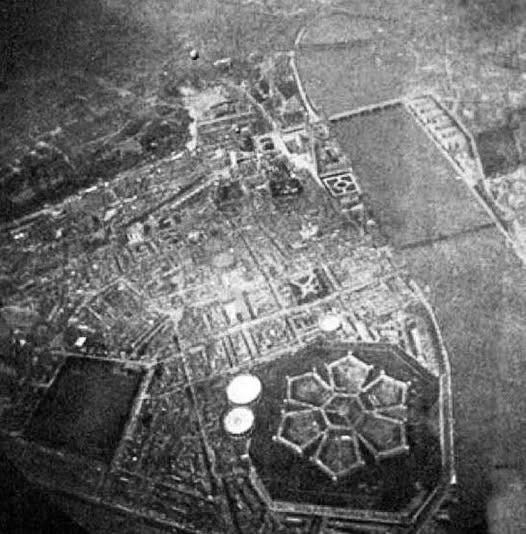

A rare photograph of the now vanished Millbank Penitentiary was taken from a balloon in the late 19th century:

Finally on this brief tour of Westminster poverty, we’ll visit the Mitre and Dove pub at the bottom of King Street and opposite Westminster Abbey:

The red blob marks the spot. The pub, and King Street, are no more. They disappeared during the creation of Parliament Square and the site is buried underneath the Treasury.

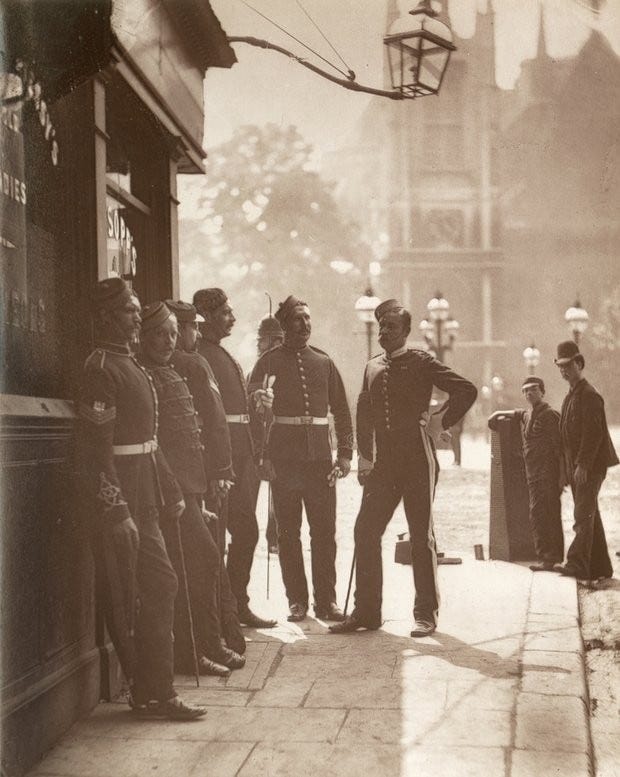

In 1877, John Thomson, a London street photography pioneer, took a photo he called ‘Recruiting sergeants in London’:

Recruiting sergeants were the "get you drunk, sign you up" press gang. One evening you’d have been supping beer in Westminster, the next morning you’d wake up with a hangover on a ship in the service of Her Majesty. It was a way out of poverty but you’d disappear off the face of the earth as far as your family was concerned. It wasn’t nice.

By the way, I’m really not a fan of colorisation, but this photo scrubs up rather well given a sympathetic use of the right AI tools. But are these uniform hues correct? Who knows?