Blackheath

Teenage wasteland

You’ve got yer London parks like Brockwell Park and Burgess Park. Manicured sections with lovely trees and flowers. Gravelled paths and a tennis court maybe - a distant thwack as a budding Venus Williams hits an ace as you perambulate. Sometimes there’s a wildflower meadow section where the council has left a bit of it unmowed so that native blooms may thrive. On weekdays perhaps lesser visited apart from dogwalkers; of a weekend full of happy families. Swings and roundabouts.

There are the commons like Wimbledon Common and Tooting Bec Common - remnants of land where our forebears had established grazing rights. London commons were formally established under the Metropolitan Commons Act of 1866, when the Metropolitan Board of Works acquired the manorial rights and largely gave them over to the growing urban public. There’s the mystery as to why South London is full of them and North London, nary an Ealing Common to its name.

But there’s a third sort: ‘manorial waste’ which ChatGPT defines as “the uncultivated, unenclosed portions of a manor’s demesne over which tenants had rights”. Thanks A.I. Your concise definition came to my rescue there.

There aren’t many left in London. Hampstead Heath was perhaps the best-known - the core of the modern heath was the waste of the mediæval Manor of Hampstead but the Metropolitan Board of Works purchased the manorial rights in 1871 so it’s a case of ‘waste no more’.

But one bit of large manorial waste is hanging on and that bit of waste is Blackheath. No trace can be found of use as common land, only as land of minimal fertility exploited by its manorial owners, mainly for small-scale mineral extraction. The freeholds are still divided between the Earl of Dartmouth and, for the portion within the Royal Manor of Greenwich, the Crown Estate. It remains one of south-east London’s largest open spaces and there’s a certain bleakness to it. You can stand in the middle of Blackheath and think to yourself: “this is a bit bleak, you know” even as you watch the traffic on the A2 rudely adding noise to the scene.

Under Section 193 of the Law of Property Act 1925, the public has ‘rights of access for air and exercise’ on manorial waste. So feel free - do a bit of legal exercise.

This post is going to be a bit of a map fest, so hang on to your hats in the breezy Blackheath wind - we’re going in.

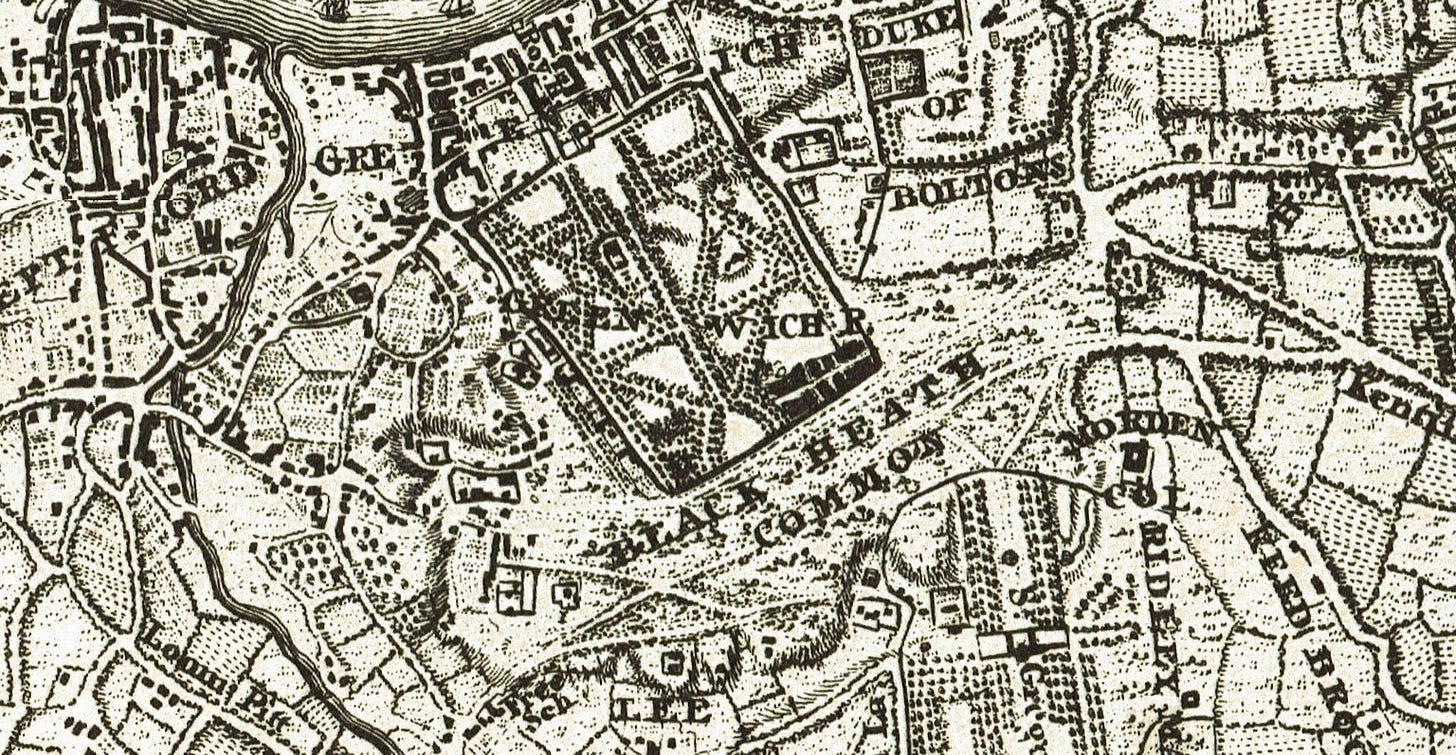

John Rocque’s 1750s map is a little bit indistinct but he’s insisting it on being called Black Heath Common at odds with all I’ve already explained. Listen, John. No grazing, no common. The windswept plateau took its name from the colour of the soil here.

Situated on the main route from London to Canterbury and Dover, Watling Street crossed Blackheath and both Roman and Saxon remains have been discovered. The Danes encamped there from 1011 to 1013 after seizing Alfege, Archbishop of Canterbury, whom they killed - probably on the site of St Alfege’s church, below the escarpment in Greenwich.

Wat Tyler gathered his followers here in 1381 during the Peasants’ Revolt and thence marched onward to Smithfield, where he was killed by officers loyal to King Richard II. It was here and at the same time that radical priest John Ball delivered his famous revolutionary sermon containing the lines “When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?” for which he was put to death.

Two points. Blackheath seems so far to be a bit of an unlucky place if you wish to avoid being killed. And if you’re not up to speed with 14th century English, John Ball was arguing during the Peasants’ Revolt that no one was a “gentleman” (noble or superior) by birth, as all were equal in the beginning. “Delved” means digging, and “span” means spinning, referring to the first couple’s labour.

For this he was hanged, drawn and quartered at St Albans in the presence of King Richard II on 15 July 1381. His head was displayed stuck on a pike on London Bridge.

Continuing the Middle Ages theme, the sole actual battle fought here was in 1497, when Henry VII routed Michael Joseph and his Cornish rebels.

In happier news, the heath was equally a setting for joyful occasions. Henry V was greeted here following the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. A lavish pageant was staged in 1540 when Henry VIII rode out to receive Anne of Cleves. More lasting in its significance was the celebration here marking Charles II’s return in 1660.

As a natural gathering place, the heath hosted revivalist meetings in the 18th century led by Wesley and Whitefield, after whom Wat Tyler’s Mound was renamed Whitefield’s Mound.

Military reviews and recreational activities also took place. The Royal Blackheath, reputedly the first golf club in England, was founded here - according to tradition during the reign of James I in 1608, later merging with the Eltham Golf Club in 1923. The first fair, a cattle fair, was held in 1689. Evelyn suspected it was intended to “enrich the new tavern” (The Blackheath Tavern?). Summer fairs continue to this day.

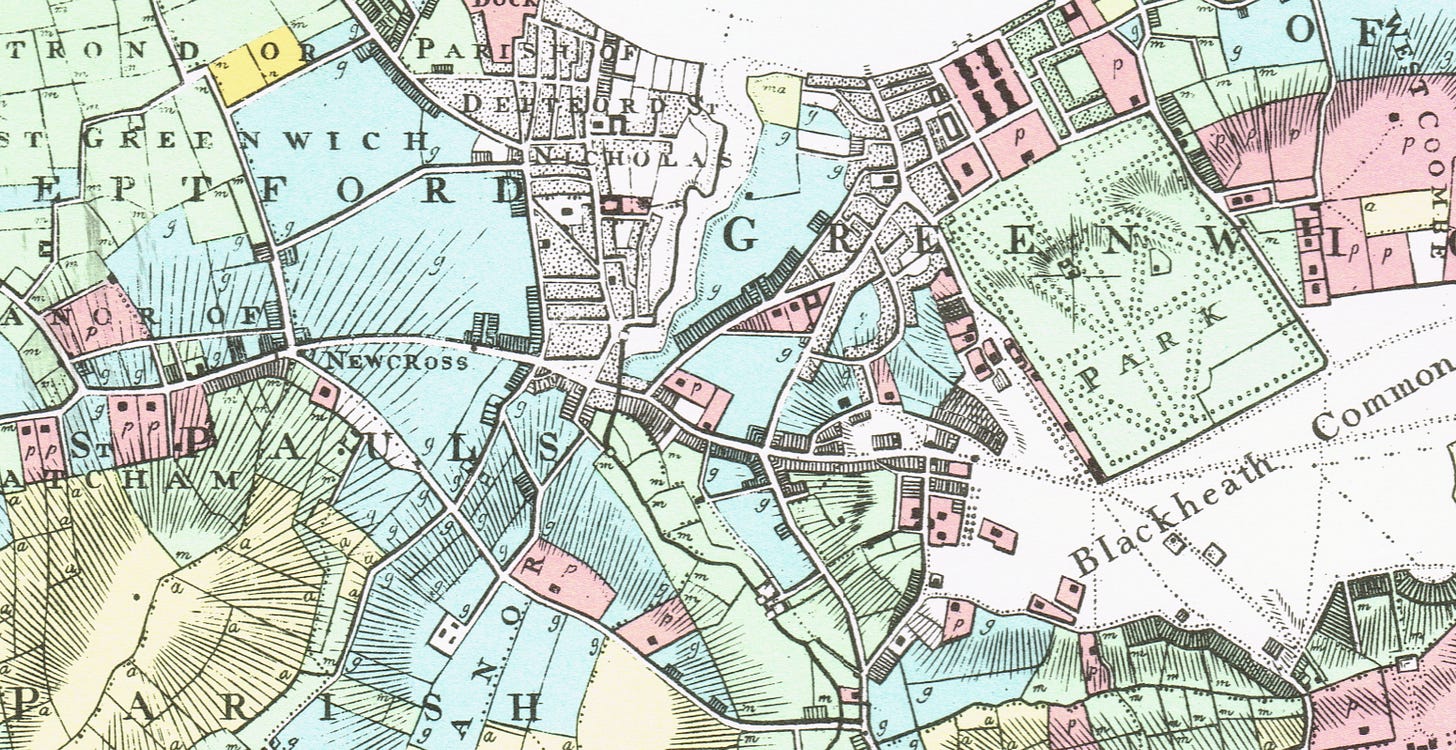

Back to the cartography, and another mapmaker making a common mistake is Milne with his 1800 landuse map.

This is a rather colourful affair as Mr Milne was adding landuse to his map. Most of the green is pasture, yellow is arable land, the blue/green areas around New Cross are market gardens and pinky red depicted private parkland which is why most of these areas have a blob of a house depicted within each parcel. Blackheath (Common) ain’t none of these and is left white.

Blackheath at this time bore a reputation for highway robbery, traversed by the notorious Shooters Hill Road. Jerry Cruncher, carrying the ‘recalled to life’ message to Mr Lorry in the opening scenes of A Tale of Two Cities, caused considerable panic among the guard and passengers of the Dover coach.

Only with the area’s 19th-century development as a residential suburb did it come to be regarded as safe. Several fine old buildings surround the heath, including the sweeping crescent of the Paragon, Morden College and Ranger’s House. All Saints’ church was erected between 1857 and 1867 to designs by Benjamin Ferrey. The Church of the Ascension stands in Dartmouth Row.

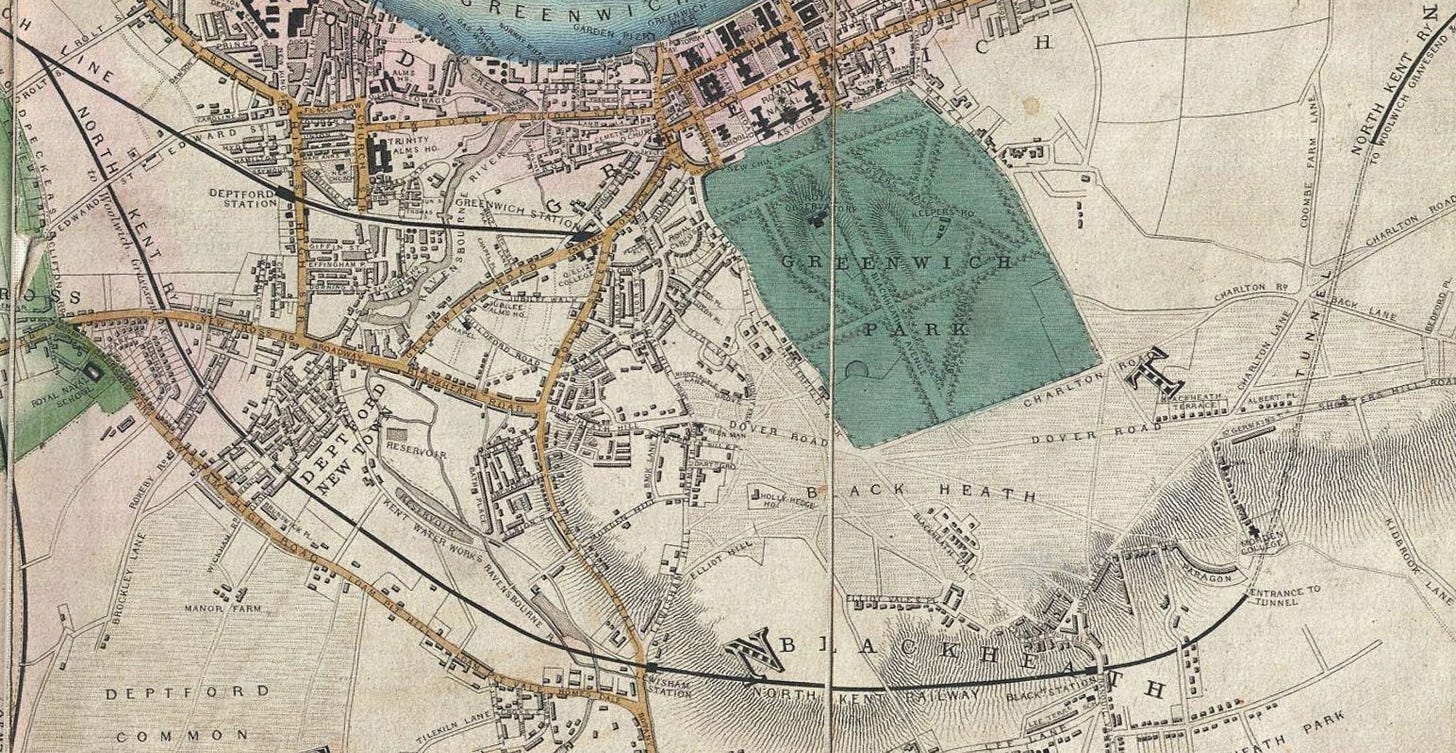

The 1852 Davies map is still showing Blackheath as a bit windswept but railways have entered the scene. Greenwich station is the eastern terminus of London’s first railway. The North Kent Railway has a tunnel under the high ground of the heath and has supplied us with Blackheath station (1849) which will spur development.

I’ve zoomed in a bit for Edward Stanford’s 1860s map. Some farm fields are just about clinging on but posh people are building posh houses around the heath. Blackheath station is just off the bottom edge of the map in Tranquil Vale, making trips into the capital easy.

In 1871, the management of Blackheath was transferred to the Metropolitan Board of Works. The acquisition came at no cost, as the Earl of Dartmouth agreed to relinquish his manorial rights.

In contrast to the heath’s long past, the village is relatively recent. When speculative building began in the 18th century, there were only a handful of cottages, two public houses and no parish church until All Saints’ was constructed. The cluster of shops now called the ‘village’ emerged in the 1820s, shaped by supply and demand. They served, as they largely still do, a prosperous upper-middle-class clientele. Rapid expansion followed during the 1840s and 1850s. The railway’s arrival allowed handsome Victorian houses along Shooters Hill Road and surrounding streets - now inevitably converted into flats. These offer a vivid, if now H.M.O. altered (thanks to Home Under The Hammer-inspired developers) impression of the area’s wealth and appeal.

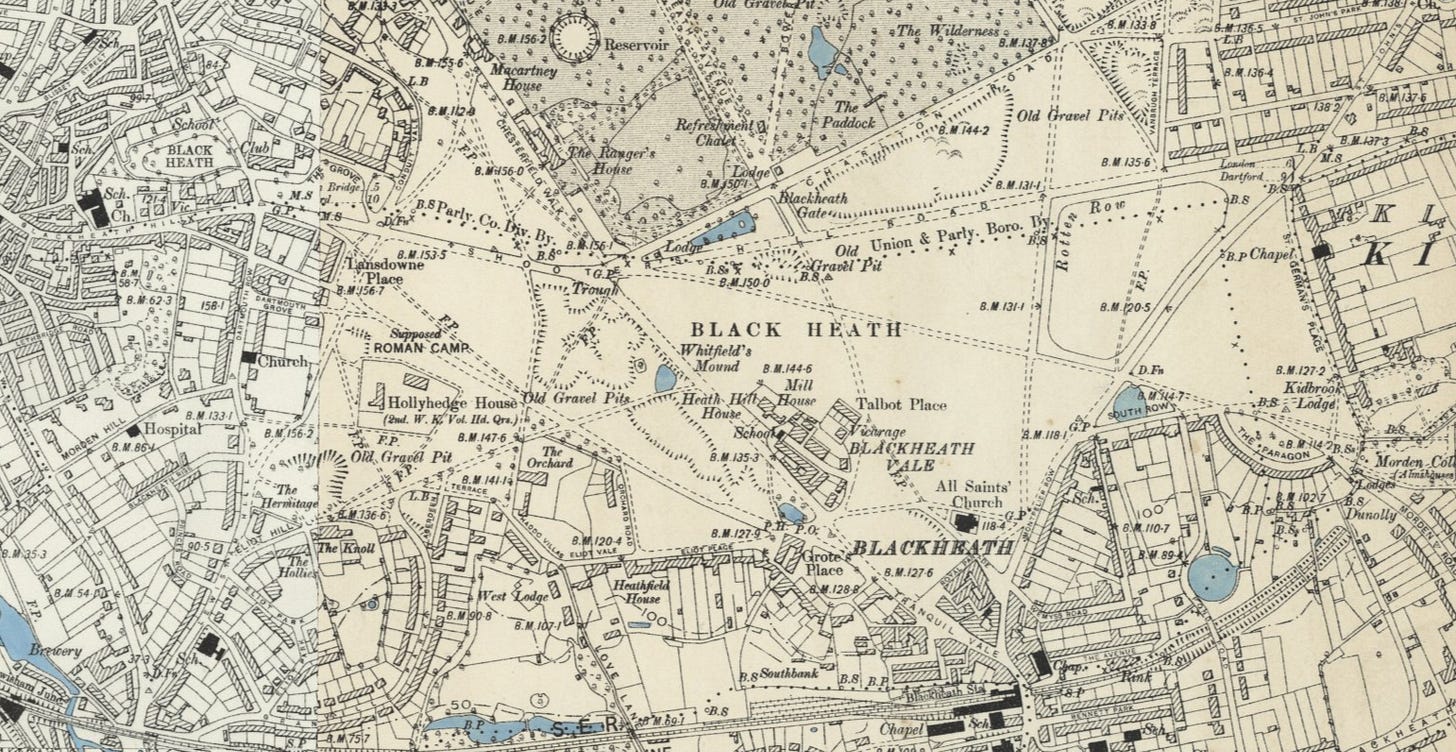

This 1870s Ordnance Survey map is just about my favourite series - just beautiful and included for its own sake.

Education was a particular preoccupation, and schools abounded of varying quality. Salem House, where David Copperfield endured the tyranny of Mr Creakle, is thought to be based on one of the worst. Few lasted long.

Miss Louisa Browning, an aunt of Robert Browning, ran a school from the 1830s until 1861. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, England’s first female doctor, was among her pupils.

The expanding Victorian community also required places for gathering and entertainment. The Green Man, at the top of Blackheath Hill - now remembered only in the name of a bus stop - had a large assembly room that served as a meeting place for years.

Concerts were held at the Blackheath Literary Institution from 1844 to 1865. Alexandra Hall opened in 1869. When rollerskating mania took hold in 1870, the rink and Rink Hall were erected on the site of the present post office. Half the rink was enclosed to form a hall suitable for performances, drama and concerts. Paderewski performed there and Henry Morton Stanley lectured (on his African expeditions, I presume). It could seat up to 1000, though railway noise made it less than ideal for musical events.

Blackheath Halls opened its doors in 1895, funded by local people to satisfy the need for a space that could accommodate large-scale concerts and meetings.

Since reopening in 1985 (after some post-Second World War time in the wilderness), Blackheath Halls has welcomed a range of artists from many musical genres – Jamie Cullum, Sir Simon Rattle, Nitin Sawhney, Paco Peña, The Tiger Lillies, Nikolai Demidenko, Kate Rusby and The Ukulele Orchestra of Great Britain. Not The Who though. I hope I didn’t lead you on with the subtitle.

I’ll squeeze in a final Ordnance Survey map from the time the twentieth century was turning.

Notable residents around these there parts have included Sir Arthur Eddington (astrophysicist), John Stuart Mill (philosopher), Donald McGill (risqué seaside postcard cartoonist) and Danny Baker (former DJ now podcaster).

The Blackheath Preservation Trust and Blackheath Society continue working to safeguard the village’s character, with no doubt a lot of NIMBY-ism.

So that’s Blackheath - an example of manorial waste.

Notes

I’d like to add that, before researching this article, I had no idea of any 1870 rollerskating mania having occurred. I like discovering new stuff while writing these that I didn’t know beforehand.

My word do I love spelling ‘medieval’ as ‘mediæval’ with the ancient æ ligature. A reminder that I can write about antennæ or archæology in the future.

Thank you for an interesting and detailed tour of this part of south-east London. A few summers ago I walked from the John Ball primary school through the heath and Greenwich Park to the Cutty Sark; it's incredible the variety of history and scenery in a relatively small area.