Alsatia

What a liberty!

Good old 19th century author Walter Thornbury wrote a book in 1878 called Old and New London. Within its dense Victorian prose, he wrote a long paragraph about the foundation of the White Friars convent.

Now, some of you will be well-acquainted with the works of Charles Dickens and others, and thus be used to the flowery prose of the era. Myself, I don’t have the patience so I’ll provide the quote and then do a soundbite version afterwards for us modern types:

In the reign of Edward I., a certain Sir Robert Gray, moved by qualms of conscience or honest impulse, founded on the bank of the Thames, east of the well-guarded Temple, a Carmelite convent, with broad gardens, where the white friars might stroll, and with shady nooks where they might con their missals. Bouverie Street and Ram Alley were then part of their domain, and there they watched the river and prayed for their patrons’ souls. In 1350 Courtenay, Earl of Devon, rebuilt the Whitefriars Church, and in 1420 a Bishop of Hereford added a steeple. In time, greedy hands were laid roughly on cope and chalice, and Henry VIII., seizing on the friars’ domains, gave his physician—that Doctor Butts mentioned by Shakespeare—the chapter-house for a residence. Edward VI.—who, with all his promise, was as ready for such pillage as his tyrannical father—pulled down the church, and built noblemen’s houses in its stead. The refectory of the convent, being preserved, afterwards became the Whitefriars Theatre. The mischievous right of sanctuary was preserved to the district, and confirmed by James I., in whose reign the slum became jocosely known as Alsatia— from Alsace, that unhappy frontier then, and later, contended for by French and Germans—just as Chandos Street and that shy neighbourhood at the north-west side of the Strand used to be called the Caribbee Islands, from its countless straits and intricate thieves’ passages. The outskirts of the Carmelite monastery had no doubt become disreputable at an early time, for even in Edward III.’s reign the holy friars had complained of the gross temptations of Lombard Street (an alley near Bouverie Street). Sirens and Dulcineas of all descriptions were ever apt to gather round monasteries. Whitefriars, however, even as late as Cromwell’s reign, preserved a certain respectability; for here, with his supposed wife, the Dowager Countess of Kent, Selden lived and studied.

The order of the Carmelites originated on Mount Carmel in the north of the Holy Land in 1150. Forced to flee from the Saracens in 1238, some members found support from Richard, Earl of Cornwall and brother of King Henry III. He assisted their relocation to England, where they constructed a church on Fleet Street in 1253.

The Carmelites established a monastery, known as the White Friars, and this extended from Fleet Street down to the Thames between 1247 and 1538. It was called the White Friars because of the white mantles worn by its monks during formal occasions. The western end bordered the Temple, with Water Lane (now Whitefriars Street) to the east. The grounds once contained a church, cloisters, garden and cemetery. Today, only a crypt remains.

The monks there respected the right of ‘sanctuary’. Anyone could turn up at the door and, whatever their crime, the friars would let them in, feed, water and accommodate them, stopping the authorities - if they turned up - from arresting the person.

Of course the great rivals of the White Friars were the Black Friars who were Dominican and wore the black cappa. They moved their 1220s-founded priory at the top of Shoe Lane (modern Holborn Circus) a few hundred metres south to be between the tidal Thames and the west of Ludgate Hill in about 1276.

You can perhaps imagine all the 13th century banter going on when the two groups living in close proximity, met. Or rather not just imagine but ask ChatGPT to write some football terrace style chanting:

We wear our white caps with pride and glory

Black Friars, you’re just a second-rate story!

Our colour’s bright, our spirit’s clear

When White Friars come, just hide in fear!

Your white caps look like washing day

We’re Black Friars, and we’re here to play!

Pale and weak, you’re looking dire

Our black caps burn with darker fire!

The Black Friars monastery hosted great occasions of state, most notably the divorce hearing of Catherine of Aragon and Henry VIII, before Henry did his 1538 dissolution of the monasteries and swept it away.

That 1538 dissolution did for the Carmelite order of White Friars too. This caused a bit of a legal anomaly - the friars had moved out and the jurisdiction of their territory had become unclear. Ownership was uncertain and it was proposed that the entitlements attached to the monastery may not have disappeared with the monks. Most importantly, the right of ‘sanctuary’ was still a part of the law, and this area could still apparently grant immunity from arrest.

On the borders of modern France and Germany, lies the Alsace. It was long disputed territory and the region gained privileges outside legislative and juridical lines to keep it sweet. The Latin neutral name (since use of the French term Alsace or the German term Elsaß meant taking sides as soon as you opened your mouth to talk about it, in a Derry/Londonderry way) was Alsatia.

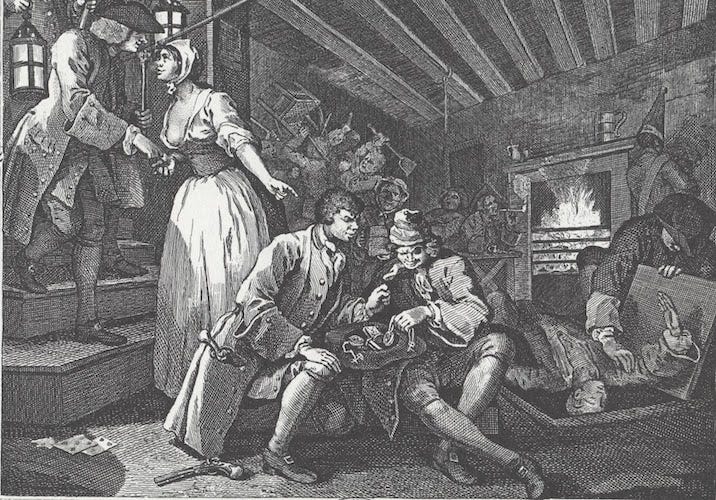

Thomas Shadwell wrote a play called The Squire of Alsatia. It was all about an area which lay beyond the law.

Alsatia became the name given to an area within Whitefriars that was once privileged as a sanctuary. The Lord Chief Justice and the Lords of the Privy Council hinted that the area remained a refuge for perpetrators of every grade of crime and only writs from the Lord Chief Justice/Lords of the Privy Council were able to penetrate its boundaries.

The crime could indeed be murder but also could be defined as blasphemy, treason and all sorts of trouble one could enter with a wrong word to the wrong company. All could come to Alsatia, London and get away with whatever.

A charter was granted in 1608 by King James I to the inhabitants of Whitefriars, acknowledging a certain measure of self-government.

This ‘sanctuary’ of Whitefriars became called the ‘liberty’ since a liberty is what you could take here.

Alsatia became inhabited by those marginalised by law, particularly debtors evading bailiffs. Infamy ensued as stories circulated about murderers seeking sanctuary and mobs deterring sheriffs.

The concept of a ‘liberty’ remained imprecisely defined. There were exaggerated assertions about criminality and tantalising hints of absolute disorder. Walter Scott’s novel The Fortunes of Nigel (1822) serves as the primary reference, despite being a fictional narrative written much later. While the book is entertaining and clever, it masks the genuine significance of Alsatia - the lives of its residents, their collective identity, political dynamics, daily experiences and autonomous spirit.

There were other religious spaces within the City previously offering sanctuary. Various liberties existed where residents enjoyed special privileges and exemptions, and peculiar territories were governed by external authorities. The Tower of London and Southwark areas contained ‘Mints’. Detention facilities like Bridewell, Newgate and The Clink maintained unique legal statuses well into the nineteenth century.

Anyhow, Walter Scott was anyway romanticising it all over a century later. Legislation and raids finally curtailed Alsatia in 1697.*

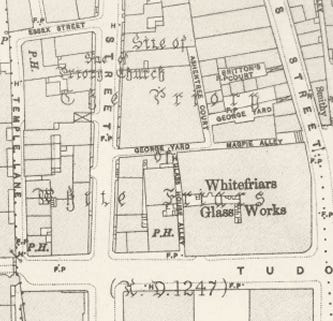

Where was Alsatia then? Instead of using a modern map which would be altered by the Blitz, I’m turning to the 1897 Ordnance Survey map. The extract above helpfully marks in a ‘oldy-worldy font’ the Site of The Priory of White Friars (A.D. 1247).

But we’re zoomed in too close to get bearings. On the next extract of the same map I’m zoomed out a bit and I coloured in red the extent of Alsatia:

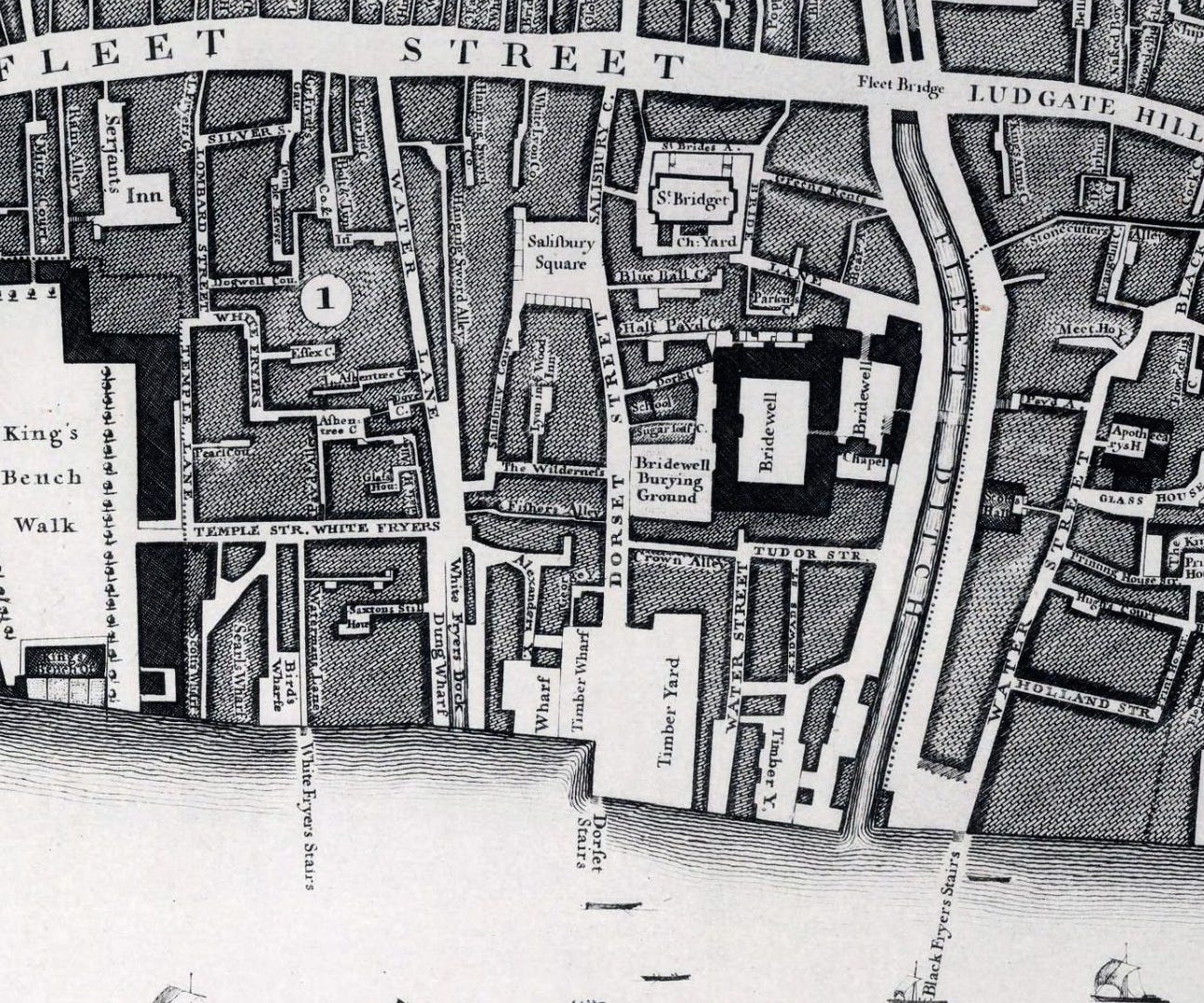

Fleet Street is mostly off the map to the north but the infamous ‘street of hacks’, Bouverie Street* leads south through the map, becoming Temple Avenue as it runs toward the Thames. This is an 1897 map so the Victoria Embankment has been constructed but Temple Avenue, Carmelite Street and John Carpenter Street all led directly to the river. Miscreants could arrive thus by boat.

The eastern edge of Alsatia was marked in 1897 by New Bridge Street leading south to Blackfriars Bridge. But this bridge was a latecomer. The John Rocque map from the mid eighteenth century shows that Alsatia was bounded by the River Fleet back in the day. Temple Avenue, Carmelite Street and John Carpenter Street - mentioned just a paragraph earlier - all don’t exist yet and most other streets had different names. But I’ll persevere.

Most of Alsatia was hemmed in by, and laid south of, Tudor Street/Crown Alley/White Fryers/Temple Street (1746 map; extended name of Tudor Street in 1897 until now).

Then there was a extension north bounded to the east by Water Lane (1746 name)/Whitefriars Street (1897 and current name).

Lombard Lane (1897 name)/Lombard Street (1746 name) and Temple Lane are the final western boundary streets.

So two things, should you be walking London any time soon and remember this post.

- there’s a footprint of an old priory now lost to time that you can walk the bounds of

- you could be immune from prosecution once around these parts

Notes

Abolished by the Escape of Debtors, etc. Act 1696. Aside from Whitefriars, eleven other places in London were named in the act: The Minories, The Mint, Salisbury Court, Fulwoods Rents, Mitre Court, Baldwins Gardens, The Savoy, The Clink, Deadmans Place, Montague Close, and Ram Alley. Further acts in the 1720s abolished sanctuary in The Mint and Stepney.

The offices of the News Chronicle a British daily paper, were based in Bouverie Street until it ceased publication on 17 October 1960 after being absorbed into the Daily Mail. The News of the World had its offices at No. 30 until its move to Wapping in the mid-1980s. Bouverie Street was also the location of the offices of Punch magazine until the 1990s, and for some decades of those of the Lutterworth Press, one of Britain’s oldest independent publishers, celebrated for The Boy’s Own Paper and its sister The Girl’s Own Paper.

Thanks for another fascinating post, Scott. I worked in the area in the early 1990s and although there were plenty of post-war new buildings, the streets, alleys and courts seemed positively steeped in history. Old London was still there, with the Thames as a constant reminder of history's flow.

Good stuff. I believe the last remaining fragment of Whitefriars is due to reopen soon as a minor visitor attraction, after years behind scaffolding. Also, you might enjoy this unhinged book by Michael Moorcock, which is part autobiography and part time-travel romp through Alsacia https://londonist.com/2015/08/michael-moorcock-s-autobiography-is-nuts